by Kevin Lively

Introduction

This article is part two of a longer series. Check out part one for my framing of the Cold War Military-Keynesianism which characterized the US and USSR economies at the dawn of the space-age.

I’ve opened many questions in my last article and I shan’t be able to close them. Oceans of ink have been spilt trying to satisfactorily answer questions of war and peace; I am not deluded enough to believe that I shall be able to do so. Nonetheless I would humbly submit to your consideration a collection of stories from the perspective of people who found themselves in a rare moment of history, when the old world order had drowned in an orgy of blood and a new one was rising from the ashes. At this inflection point in history, questions of land, power and death were in open debate within global centers of power which were endowed with a freedom of decision-making rarely seen in the long history of international affairs. If you fear, as I do, that this historical precedent bears increasing relevance in today’s geopolitical climate, then we should seek to understand the perspectives of these long dead warlords, the considerations which shaped the world and the consequences which we as a species continue to grapple with.

Topics this large must necessarily be broken into multiple essays. In this one I shall begin with the choices made at the end of WWII to recover from what may as well have a stage rehearsal for the apocalypse. I want to chart how, in quieting some of the guns around the world, US military spending transitioned through its low-point in 1949 into an abrupt reversal — leading to a steady-state war economy at the outset of the Cold War in 1950. The course of events underlying this coincided with an onset of USSR nuclear capability, the “loss of China” to the Chinese Communist Party, and the beginning of the Korean war, all while setting the stage for Vietnam. Here I will only have space to begin this story.

Framing the Narrative

Captain Hindsight is the patron saint of historians and armchair generals alike. After the primary actors are long buried and the security situation so changed as to make classification irrelevant, the internal planning documents which weren’t hastily burned are finally released. The USA in particular used to have a strong commitment to regular declassification of non-technically sensitive material. Internal planning documents from WWII and its immediate aftermath were slowly released within a roughly 30-40 year time horizon, continuing into the 1970s. One can peruse to their hearts content much of the internal records of US administrations up to Carter before the share of still-classified topics begins to balloon out of proportion. Nowadays one is reliant on the occasional leak, either from sites like Wiki leaks, The Intercept or somewhat bizarrely and with increasing frequency, video game servers like War Thunder.

What you will notice when going through the official record from the Office of the Historian, is that while many topics up to Carter are perfectly available, for example the build-up to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan or security considerations of sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern Europe, there is an ongoing blind spot in the official record of US policy planning towards Western Europe. Upon reflection this is a somewhat odd state of affairs. Why should the internal planning for relations among allies remain classified nearly half a century after the events in question?

To begin prying this thorny question apart we must take stock of what resources are available to us. This means looking at the state of affairs after the end of the war, as seen from inside policy planning circles in the USA. Our hope will be to obtain some understanding of what the self-declared interests and capabilities were for officials in the State Department and the Department of War as the power relationship which would characterize European affairs for over half a century took shape. From these internal considerations we can make a broader attempt to extrapolate the analytical framework in which later participants were acting once the record runs dry.

Again, as with nearly every interesting topic in history, the narrative framing of this question is itself immediately suspect. Which war or set of wars am I referring to?

In the United States, WWII has a glorified canon reminiscent of a Christmas panto. Among some circles of mid-2000s History Channel enthusiasts it can practically be sung aloud in choir akin to a carol. Feel free to sing along if you know the words. After one too many appeasements Czechoslovakia is eaten by Germany and Hungary. Joe and Adolf divide Poland between themselves with the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and the French and British declare they’ve had enough. After six months of posturing through the Phoney War, Hitler sweeps through France, Dunkirk grosses $530 million at the Box Office, and the Battle of Britain rages from 1940 to 1941 before Germany cedes the skies over England. The Germans and Russians put the atrocities of The Great War to shame in an ocean of blood in Eastern Europe. The Japanese attack Pearl Harbor at the end of 1941 despite the Americans having already taken the unprecedented step of a peace-time draft in 1940 — despite domestic assurances of a policy of peace from FDR in his 1940 electoral campaign — are dragged in. Germany makes the fatal mistake of also declaring war on the Great Power of the western hemisphere.

Outside a collection of middle-aged armchair-general suburban dads who specialize in the subsequent history — or on a serious note, those whose family was involved in the ground level fighting — the modern popular imagination generally montages the next four years in a haze of Tom Hanks movies, Band of Brothers episodes or Call of Duty sequels until the radioactive dust has settled over Nagasaki on August 9th 1945. This is one perspective on this apocalyptically destructive global trauma, from a jaded millennial’s North American viewpoint.

The Colonial Underpinning of WWII

Another perspective of this conflict begins with the Japanese invasion of Manchurian China in 1931. That story runs through the Spanish Civil war in 1936 in which the Luftwaffe flexed its wings in Guernica, and continues through the conclusion of the Chinese Civil war in December 1949. We could even, I think reasonably, argue a historiographical grouping which extends through the First Indochina War of 1946-1954, the Indonesian National Revolution and the Korean war, which all overlapped within 1946-1954. Recall that these events were, resepectively, when the French were one-half to a vain struggle which killed half a million people in order to re-establish their colonial rule in Vietnam, almost 100,000 people died while the Dutch tried the same in Indonesia, and virtually the entire Korean peninsula traded hands between warring armies multiple times, with nearly 3 million dying in the process so that two authoritarian regimes could be founded. Every one of these conflicts was a direct consequence of the often brutal Japanese occupation of these places, and thus their defeat by the British and Americans.

If we take the perspective of this “Long Second World War”, in a spirit analogous to the historiographical tradition of the “long 19th century” we can see the contours of a much different narrative. In this picture, the western powers and Russia, hostile enemies who had only ceased active military operations against each other when it became clear that the Bolsheviks had won the Russian Civil War, briefly set aside their differences to crush an expansionary and autarkic European Axis of industrialized countries. However, when the line of contact between Russian and western armies met once more in 1945, hostilities quickly resumed, now taking place in the German heartland.

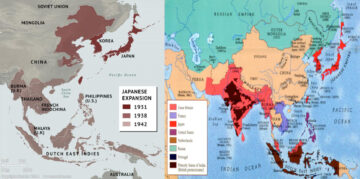

Japan meanwhile had grown disillusioned with its status as an “honorary white nation” in the post-WWI order. Decades after the dismissal of the principal of Racial Equality from the charter of the League of Nations, and as a propaganda justification of its increasing Imperial holdings, it turned towards the rhetoric of a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere“. In this widely propagandized vision of the world, the Japanese would kick the western imperial-colonial powers out from their overseas possessions in a recreation of the Monroe-Doctrine for East Asia. This promise was actually kept across much of the western arc of the Pacific and Indochina, though at the cost of brutal Japanese Imperial Dominance. The Japanese supernova occurring in parallel to developments on the Western side of the Eurasian landmass unmoored European and US investments in the shattered Chinese mainland, destabilized the French and British rule of Indochina and kicked the Dutch out of Indonesia while Japan deployed troops off the coast of Australia. This expansion massively destabilized the capacity of the imperial core in western Europe to obtain raw resources for their war machines right as their heartlands were under direct German assault or occupation.

This broader context, often forgotten in modern American culture’s ongoing hagiography of WWII, was certainly not lost on the American population at the time, who could see clearly what was being asked of them. The legendary folk singers Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie for instance contributed to an album in 1941 which complained bitterly about the peacetime conscription bill, asserting an unwillingness to die for British colonial or American industrial interests. Among accusations of being funded by both the Nazis and the Communists simultaneously, this album was suppressed by Roosevelt despite Eleanor being an erstwhile fan of folk music.

The mobilization of the American Economy meanwhile, shepherded by a Department of War with extensive logistic experience from the previous European conflict, was focused through the lens of an executive branch of government which had been vigorously building New-Deal agencies for seven years. As anyone who has ever hiked a trail which was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps or listened to ethnographic recordings of folk music and history will tell you, the government had already been mass organizing American civilian labor since 1933.

With the political willpower that comes from being under external attack, the government’s expenditures as a percentage of GDP in fixed 1940 dollars shot from 9.3% in 1940 to a peak of 46.5% in 1943, with defense accounting for 89% of federal spending by 1945. It need hardly be said that the conscription alone would put a dent into unemployment, let alone cranking out 151 aircraft carriers in the course of the war. For context, a single modern, albeit vastly more advanced, nuclear powered carrier took the span of 2005-2017 to be built and delivered.

For a population wary of a return to the Great Depression, and with tens of millions of refugees looking for food, shelter and work in a world still at war, the lessons learned from this experience set themselves deep in the traumatized psyche of the public and policy planners alike.

The Emerging Phoenix

The momentum of events in history, when viewed from the safe harbor of the future, seem to embody a certain logical inevitability, which takes the shape of certain clean looking narratives. One such emerging narrative concerns the overlapping domestic and economic interests which coalesced in the afterglow of the celebrations of VE and VJ days in the USA.

By this point unemployment was less than 5% and defense spending was 46% percent of American GDP. Many of these domestic jobs were, broadly speaking, good paying, unionized and provided unique opportunities for women and African Americans. This retooling of New Deal liberalism, originally meant to sand the rough edges off of capitalism, led to a confluence of interests which cut across traditional divides of workers and owners, conservatives and liberals. Capacity for warfare in a chaotic world has an apparently unassailable self-consistency to it: “If we don’t build it, they will”. This consolidation of interests ultimately led to widespread support for the continuation of military production. This was not necessarily a natural evolution for such previously divided sectors of society. Indeed the cultural, societal and internal geographic tensions inherent to the United States quickly resurfaced after the conclusion of the war, as can be seen by widespread strikes in 1946.

From a top-down domestic policy perspective, one could view the decision to cement a permanently higher expenditure in the war economy as simply the politically easiest option that Truman had from 1945-1953. Recall that Truman was a relatively inexperienced politician and had only been vice-president for 82 days before the longest-ever serving US president died. Truman’s inclusion in high-level meetings in the administration was so minimal that he is cited as not even being aware of the existence of the Manhattan Project, Joanna Gillia, pg 20. After being sworn in to office, Truman was barraged by torrents of backlogged top-secret briefings on the strategic situation from departments covering issues around practically every aspect of the global economic and military situation.

We should keep in mind what the apocalyptic chaos of Eurasia looked like from inside the USA after Germany’s capitulation. The Japanese Imperial war machine was still bloodily resisting in the Pacific even as it became increasingly obvious that the Japanese Navy had been eliminated as an effective fighting force. With the European front utterly dominated, the Great Powers met outside the smoking rubble of Berlin from July 17 to August 2 1945 in order to settle issues of control over the line of contact and of Berlin itself. It was obviously imperative to everyone involved that the priority of this meeting was to prevent another tsunami of intra-European violence from engulfing the world again. This is an unenviable position for even a master strategist to find themselves in, irrespective of what Truman’s personal capacity for statecraft may have been at the time.

However, the final detail of note was the success of the Trinity test which, at Truman’s insistence, took place literally on the first day of the conference. Thus Truman enters these negotiations knowing he has a god like super-weapon in his back pocket. In the end Truman did not swagger into the opening meeting like a nuclear armed cowboy. Instead, due to the years of continuous planning which ultimately won the war, the State and War Departments were obviously well prepared to best argue for the balance of power which would most benefit the US’s multifaceted objectives.

Like every collection of humans ever assembled, chief among theses objectives was “to prevent physical invasion, attack or enslavement“. To this and many other ends, the Briefing Book papers marked Top-Secret in section III: “European Questions”, Documents 222-225, in “Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic papers” give a very concise overview of many relevant factors concerning in particular the role of Western Europe. Given that much of the planning around Western Europe from more recent administrations remains mostly classified, this provides an opportunity to see what could have been motivating planners in later decades.

We can learn, for example, that France obtained a seat on the UN Security Council despite it’s “almost pathological craving for prestige” because of its influence over Frankophonic regions. This inclusion of France “prevented her from siding with the lesser powers” during the chartering of the United Nations in San Francisco. The final structure of the charter which came out bears some suspicious resemblances to past pecking orders in Great Power security arrangements such as the Concert of Europe. In that post-Napoleonic equilibrium, land conflicts within Europe between the Great Powers decreased somewhat during the 19th century while Britannia’s rule over the waves forged the Pax Britannica. You are permitted to salute the nearest Union Jack at hand.

As you know the UN is composed of a heavily armed “Security Council” and largely toothless “General Assembly”. Recall that many members of the General Assembly in 1945 were either nominally independent colonial possessions or their foreign policy was almost completely constrained within the sphere of influence of a greater power. The most obvious case of the latter is most of the countries in the Western Hemisphere under the USA, and one example of the former would be the US colony of the Philippines. One memorable turn of phrase concerning France joining the Security Council is that “It is believed that the responsibilities which such participation implies will, at least in the immediate future, act as a curb on her impulsive and petulant instincts”. It’s almost charming to see a continuation of the long English tradition of slagging off the French manifest at the highest levels of US diplomacy.

Speaking of the United Kingdom, its ongoing inclusion among the “Big Three” alongside the USA and USSR appeared to be falling under scrutiny by July 4, 1945. Despite his bluster as the defender of British Empire, in actuality Churchill did not legally speak for the Dominions in the Commonwealth such as Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. This political and geographical decentralization proved to be a liability to the massively bankrupted Crown government. Nonetheless this collection of ‘small and “medium” sized powers’ were “represented” by the UK despite the fact that “There are undoubtedly secrets which the [UK] does not or cannot share with [the Dominions]”.

For their part, the British were probably just relieved that the Potsdam conference was happening at all. When the line of contact consolidated across Germany, British war planners quickly assessed what would happen if the shaky truce between the western and Soviet armies would fail to hold. In a report entitled “Operation Unthinkable“, among the assumptions for that thought experiment were that hostilities could open by July 1st, 1945, and that in this circumstance the allies would “have full assistance from the Polish armed forces and can count upon the use of German manpower and what remains of German industrial capacity”. As could well be imagined there is only one goal listed for the objective of such an action: “The overall or political object is to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and British Empire”. Looking back at the picture of Stalin and Churchill, consider that due to the spy Guy Burgess, Stalin was aware of this document, having re-positioned his forces at the end of June in apparent anticipation.

However in a brilliant stroke of analytical insight, the military planners pointed out that USSR forces outnumbered Allied forces in Central Europe by a factor of three. Even with the Allies’ superior organization, equipment and morale, if Russian forces were not rapidly rendered ineffective in such a strike they would simply withdraw into the vast Steppe which had just killed or captured over 9 million Axis troops.

In this scenario of a protracted conflict, the machines of total war which had been honed to razor sharp precision over the last five years would slam into full gear once more and victory for the west would

“require, in particular, the mobilisation of manpower to counteract [the USSR’s] present enormous manpower resources. This is a very long term project and would involve [both] the deployment in Europe of a large proportion of the vast resources of the United States [and] the re-equipment and re-organisation of German manpower and of all the Western Allies.”

It is no coincidence that the following briefing book paper in the US Diplomatic collection, document 224 concludes that to hedge against this scenario, the nations of the west would draw together in a Western Security bloc, not only to present a unified front against the Russians but crucially to also restrain Germany from re-militarizing. Britain envisioned them as being drawn to the commonwealth, perhaps in an echo of the Franco-British Union that was proposed back in 1940. As events played out, it was not to be the UK but the USA which solidified this western alliance. Thus we come to the origins of NATO.

Next time I will discuss this processes of consolidation of the Allied powers without Russia, and explore how the USA was obliged to support French reassertion of control over Indochina out of a necessity to support the economic recovery of Europe. I will explore how growing tensions on the western front dovetailed with the deteriorating situation on the East Asian front which climaxed with the Soviets getting the bomb and the “loss of China”. These culminated in National Security Council Paper NSC-68 in 1950, full text here. This document set out the broad contours of the following 40 plus years of the Cold War with startling accuracy, and is a striking insight to how desperate attempts to manage the course of global affairs look from the inside.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.