by David J. Lobina

This is a question I was considering whilst reading this recent paper by Dorsa Amir and Chaz Firestone on the origins of a well-known visual illusion (a preprint is freely accessible here). It is an issue I have often thought about, and about which I have always wanted to write something. It is a question that attracts the attention of most scholars who study human behaviour, and most scholars will have a particular idea as to what their “first principles” are when it comes to constructing a theory of cognition.

Where does one start from when building up an account of a given cognitive phenomenon, though? Are there any initial assumptions in this kind of theoretical process? I think it is fair to say that in most cases one’s first principles can go some way towards explaining what kind of theory one favours to begin with, though this is not always explicitly stated; an enlightening case in this respect is the study of language acquisition, as I shall show later.

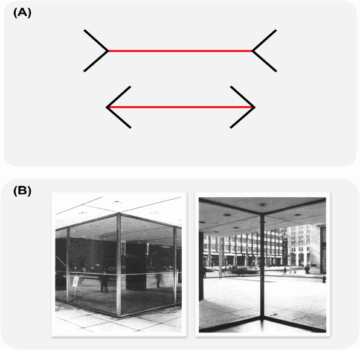

Let’s keep to Amir & Firestone’s study for a start. The paper focuses on the Müller-Lyer Illusion, shown in graphic A below, taken from their paper, an illusion that goes back to 1889 and is named after Franz Müller-Lyer, who devised it. Why is it an illusion? Well, because the two lines are of the same length and yet one typically perceives the top line to be longer than the bottom line, even after being told that they are of the same length – and even after checking this is so with a ruler. The Müller-Lyer Illusion seems to be unaffected by what one knows about it, and thus would be a candidate for a perceptual process that is more or less autonomous – it simply applies because of how our visual system works.

Or does it? A typical rejoinder has been that culture can shape the way we perceive the world in rather significant ways, and as a matter of fact not everyone is as susceptible to the Müller-Lyer Illusion as the western, educated population that is usually tested in cognitive psychology labs (this cohort is sometimes referred to as WEIRD; google it). Indeed, many cross-cultural studies have concluded so, and as a possible explanation it has been argued that the Illusion arises in populations who have been brought up in carpentered environments, shown in graphic B above – lacking this background, the Illusion is not as robust. Thus, the Müller-Lyer Illusion would be a product of experience and its observers might just be the exception rather than the rule.

Amir & Firestone do a good job of highlighting the shortcomings of the many studies claiming that culture affects susceptibility to the Müller-Lyer Illusion. In particular, they point out that many studies conflate various factors and are internally inconsistent, often contradict each other, the data are sometimes misinterpreted, and some results are not always replicable. But I defer to their paper for the relevant details.

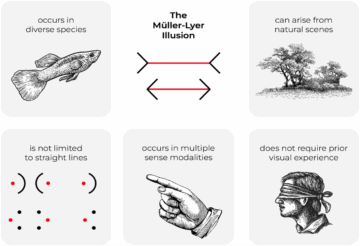

More significantly is Amir & Firestone’s demonstration, summarised below with another graphic from their paper, that the Illusion also occurs in other animal species, it does not depend on carpentered environments and in fact arises in natural scenes as well, it is not even limited to straight lines, it comes up in other modalities (including haptic stimuli), and it does not require prior visual experience (as in recovered congenitally blind individuals who are just as sensitive to the Illusion as seers with plenty of visual experience). I again defer to Amir & Firestone for details; here I want to focus on the repercussions stemming from it, in particular the paper’s conclusion that the Illusion is not the result of cultural acclimatisation.

A corollary of all this, as Amir & Firestone discuss, is that the Müller-Lyer Illusion may well have its origins in innate and ancient evolutionary biases – it may be a design feature of our visual systems. And given that all human beings, no matter their culture, descend from the very same ancestor, we should expect the Illusion to reflect a universal feature of human cognition (universality over diversity, as I have put it elsewhere; or diversity within universality, to be more accurate).

Another corollary is that it may be safe to assume that in many of the so-called “basic psychological processes” – e.g., working memory, visual perception, etc – universal effects ought to be the norm rather than the exception. Such an assumption would constitute a “first principle” regarding how to approach the study of human cognition – viz, that some of our cognitive systems have been shaped by evolutionary processes and are thus universal – and this certainly yields a particular theory of cognition.

Before getting to that, let me stress that most cognitive scientists are aware that behaviour in all its richness is an interactive phenomenon through and through. That is, there are many factors at play in effecting most behaviours, from various cognitive processes (working memory capacity, attention) and environmental factors (upbringing, context) to diverse mental states (beliefs, desires) and also general knowledge, including about one’s past (stored in long-term memory). This is a given, and to be sure it does make the study of human psychology a tricky endeavour.

However, what is remarkable about cognition is that there appear to be a number of mental processes that operate, as alluded to earlier, more or less autonomously, and this suggests a particular way to study cognition. The impetus for such an approach may well have started with Jerry Fodor’s The Modularity of Mind, a book from 1983, where the Müller-Lyer Illusion is prominently discussed, and where Fodor argues that the human mind is subdivided into a number of components, including a limited number of mental modules that only have access to proprietary information when in operation – i.e., these modules can employ information that is particular to their modality (visual, aural, etc; modules are perceptual systems under this view); or as Fodor put it, mental modules are informationally encapsulated.

If this is the case, there couldn’t be (m)any “top-down” effects on processes such as visual perception or language comprehension (two of Fodor’s candidates for modular status), by which it is meant that the operations of these modules would be unaffected by one’s beliefs, emotions, etc – by cognition tout court, that is. Or put another way, and following the psychologist Zenon Pylyshyn here, a close collaborator of Fodor’s: modules are cognitive impenetrable (from the rest of cognition).

Pylyshyn’s framing has been very influential in cognitive science and is part and parcel of Amir & Firestone’s analysis (Firestone has some form here; this other paper of his is similar in kind to his work with Amir, just as thorough, and eventually focused on showing that, many studies to the contrary, there are no top-down effects on visual perception). Accordingly, if you find this line of argumentation appealing, then your theory of cognition will start from the assumption that certain psychological processes are impenetrable, not affected by cognition overall, and mostly proceeding autonomously instead.

As mentioned, Fodor argued that language comprehension is also modular in character (or, perhaps more accurately, that sentence processing is modular: the assigning of syntactic structure to linguistic material). I think that’s certainly the case for some operations of sentence processing, but for the purposes of what I am trying to put across in this post I want to bring up the (not unrelated) case of language acquisition, as one’s initial assumptions here can significantly determine what kind of acquisitional theory you support.

In general, the study of language acquisition can be approached from different theoretical perspectives, often accompanied by distinct assumptions and commitments (first principles, that is). This is perhaps most evident in the competing accounts offered by the two major approaches to language acquisition: the Generativist and the Constructivist (this is an oversimplification, but let it stand). The former is based on the idea of an innate universal grammar guiding language learning, and originated in the work of Noam Chomsky, whilst the latter is connected to emergentist, socio-pragmatic, and functionalist ideas of linguistic structure and language learning, with its best representative perhaps Michael Tomasello.

It is important to note that both approaches assume an innate base, in fact, be this in terms of capacities/mechanisms or knowledge/representations (or both). The issue is that whilst the Generativist tends to argue for a rich and sophisticated body of per se linguistic information that is available ab initio, the infant’s task the selection of the right combination of “representations” and “rules of formation” in response to their linguistic input, the Constructivist tends to reject any innate linguistic base, the child’s linguistic knowledge emerging gradually instead through a combination of innate socio-pragmatic capacities (such as mind-reading) and domain-general pattern extraction systems.

Which approach is favoured in the field, though? Perhaps unsurprisingly, the debate between these two perspectives has not been settled by the data, the interpretation of which is contested at every level. Whilst this lack of consensus doubtless reflects certain differences in the core theoretical assumptions of the approaches, it also reflects the inconclusive and patchwork nature of the evidence itself. Indeed, the situation is such that both approaches can legitimately draw on evidential support, with neither conclusively confirmed or disconfirmed. The lack of conclusive evidence has not prevented anyone from vigorously claiming the acquisition of any specific feature of language for their own.

Thus, Generativists claim the overall evidence base in favour of children’s innate capacity, with children’s differential performance on a given linguistic phenomenon (an aspect Constructivists emphasise), taken to reflect either relatively minor lexical variation or certain extrinsic factors (e.g., overall complexity of certain linguistic structures or the pragmatic contexts in which these are usually elicited in an experiment). Thus, to come to the other side, Constructivists claim the evidence base in favour of an emergentist account that sees children starting without any innate linguistic, this knowledge instead derived entirely from discourse-embedded patterns in the specific linguistic input that the child hears around them, with children gradually abstracting over constrained and item-specific constructions.

Be that as it may, whatever theoretical viewpoint one adopts, the study of language acquisition faces two fundamental motivations, and it is against these that one must decide what the initial assumptions of a theory of language acquisition must be based upon.

First, the main business of language acquisition takes place over a rather short period of time (4 or 5 years), something that clearly requires some sort of causal account if we are to have a genuine explanation of this phenomenon. Second, at each stage of the acquisition process, children’s evolving knowledge of the language to which they are exposed is both systematic and constrained, which is to say that children’s comprehension and production outputs exhibit an internal logic and are certainly not random (patterns are observable).

So, what would your first principles be here, then?

Consider the first motivation, well, first. This may sound trivial, but all else being equal, any child from anywhere in the world, no matter the culture they are brought up in, will learn the language they are exposed to natively, and they will do so quickly and without any formal teaching (what’s more, they’ll learn the local language natively even if this is different to their parents’ own native languages). Indeed, by the time children begin their primary school education at around age 5, they have already acquired the core aspects of their language. They will naturally expand their linguistic knowledge greatly during schooling, but no child needs to be taught how to speak in school. Children are predisposed to learn a natural language, and for the most part they all reach more or less the same standard by age 5.

What’s more, children follow roughly the same schedule, as it were, in doing so. On the production side of things, and as new parents will recall being told by one medical expert or another, children start babbling at around age 9 months, start producing single words at age 12 months, two-word phrases from age 18 months, short sentences from 24 months, and multi-word sentences from age 30 months or so. On the comprehension side of things, and not everyone is told about this, tragically, children are sensitive to the phonological properties of language from the time they are born, if not earlier, as they are especially attuned to the properties of the language of their parents, which they would have been exposed to whilst in the womb already. Moreover, many studies have shown that, by employing experimental techniques that probe the comprehension skills of infants, these children demonstrate that their knowledge of language is more sophisticated than what their actual production seems to indicate – that is, they understand many linguistic structures before they can produce them themselves (the latter requires motor-skills that develop at a delay vis-à-vis their linguistic knowledge).

And all this no matter the nature of the linguistic input they receive or parenting style (not every culture partakes in so-called motherese, for instance); what’s important is that children are exposed to language in normal circumstances from early on. In fact, there is plenty of evidence for what is usually called the “critical period of language acquisition” – that is, the period in ontogeny when children need to be exposed to language, lest they lose the ability to acquire a language to begin with, which appears to be the very first 4-5 years of life I have focused on. A relevant case here is that of Genie, who had been severely neglected as a child until being discovered by the authorities by age 13, and who was unable to acquire a language fully from then on (a complementary question is the critical period in learning a language natively, which seems to be a longer period, perhaps to age 10; see here for some data, but I should stress that this point applies under the assumption that one has been exposed to language in the first 5 years).

The Generativist sees much here to support their own first principles, of course, including their proposal that our capacity for language is akin to our visual systems – the latter too require exposure to the relevant environmental stimuli from early on in ontogeny for its development, more like an organ than a learned skill in that sense. The Constructionist, it may be argued, find themselves in a more perilous situation, with their insistence on language acquisition being mostly data driven as well as their tendency to focus on production data rather than on comprehension data as evidence of linguistic knowledge, to the point that Tomasello has often stated that language acquisition starts at age 1, when children start to use single words in order to communicate more explicitly, thereby assuming that the first 12 months constitute a pre-linguistic period in child development.[i]

The disagreement between the two camps is reinforced by the second motivation, which I have already broached – namely, that children go through various phases during the language acquisition process, and their outputs, be these comprehension- or production-based, exhibit certain patterns, including the mistakes children make. I say mistakes, but it is more accurate to say that during the language acquisition years children are forming a mental grammar for the language they are exposed to and it takes a few years for the mapping between one and the other to match up properly. But two things about these “mistakes” are noteworthy: 1) children follow a progress all of their own, in the sense that their outputs are often not amenable to parental correction, but then, at one point and suddenly, children stop making certain mistakes; and 2) the mistakes they do make are not random at all, but reflect well-known properties of language, as the mistakes in fact reflect possible structures of language – of some attested language, even if at a certain point in time these may not match the target language.

This is not to say that language acquisition is not data driven in a meaningful way – children do need to be exposed to language, to interact, to do things with language – but there is a bit of a paradox when it comes to the causal role input data actually has when learning a first language. This is also true of cognitive development in general, and by the extension it has an effect on the discussion on first principles and kinds of theories I am conducting.

Take Tomasello’s theory of language acquisition (e.g., here). Such theories offer too tidy and organised an account of what happens during the acquisition of language, and it seems to me that such accounts are based upon too strong a set of assumptions (what I have been calling first principles, to labour the point). According to Tomasello, language is learned in stages and children build upon what they have learned and mastered at each stage, thereby exhibiting an ever more sophisticated knowledge and set of skills (Jean Piaget, and more recently, Susan Carey, have put forward similar staged accounts for cognitive development).

The problem with this is twofold: first, it is unclear how children can in fact build stage B, say, with the knowledge and skills they have in stage A, as quite often the later stage is qualitatively different from the previous one and almost unrelatable (Fodor saw this as a paradox involving the learning or constructing of a representational system that is more expressive than the one you already have); and, secondly, and perhaps more importantly, these accounts outline a stage-by-stage account that makes perfect sense just in case the posited operations, and the data that these operations need, happen to be uniform and the same for, well, everyone everywhere.

And it is the latter assumption precisely that strikes me as unsupported: the relevant factors (different cultures, different parenting styles, different kinds of linguistic data that children are exposed to, etc) are contingent and can’t be regarded as universal in any way, let alone part of a stage-by-stage theory where everything is in (the right) place and is supposed to apply to everyone. And yet it is the result of the language acquisition process that is, all else being equal, most certainly universal in nature.

So, where should your theory of language acquisition start from, then?

[i] The very last point is, in one sense, untrue, given that children are parsing phonological properties of the input language since birth, and thus are in fact being linguistic creatures from the off – there is no pre-linguistic child in any strict sense of the term. I should add that there’s a more fundamental disagreement between the Generativist and the Constructivist in that these two camps see the very nature of language differently – for the latter language is a medium of communication (and, hence, their focus on the production of language), whilst for the former communication is one of language’s uses, but not the main one.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.