by David Kordahl

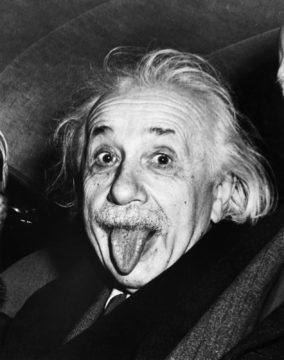

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when the picture was taken. But public memory is fickle, and today only the man on the right is still recognizable to most people.

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when the picture was taken. But public memory is fickle, and today only the man on the right is still recognizable to most people.

Albert Einstein, Time Magazine’s “Man of the Century,” the father of special and general relativity, has a place in science that remains secure, regardless of what one thinks of his life as a whole. Despite activist efforts at demystification, Einstein the scientist is unblemished by any misgivings about his personal life or political activities. Robert A. Millikan, the bow-tied man on the left, is far less secure. The posthumous charges against Millikan have been against his scientific integrity and his political sympathies, and his detractors have made headway.

In 2020, Pomona College changed the name of their Robert A. Millikan Laboratory, noting Millikan’s “history of eugenics promotion,” along with his purported sexism and racism. In 2021, the California Institute of Technology, the institution that Millikan spent decades building, followed suit, renaming Millikan Hall as Caltech Hall, and discontinuing the Millikan Medal, previously the Institute’s highest honor. Citing Caltech’s precedent, the American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT) renamed its own Millikan Medal later that same year.

Since I spend most of my time teaching physics, and since I am myself a member of the AAPT, it was the last of these name changes that rankled me the most. These allegations bothered me because I suspected that they weren’t quite fair. Read more »

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.