by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

In heaven, there will be no more sea journeys, says Virgil. For much of human history, to journey by ship across open waters was thought of almost as an act of transgression. It was something requiring great temerity and audacity. It was therefore something not to be taken lightly.

Crossing boundaries, such journeys often ended in ruin.

CS Lewis once described the people of the Middle Ages, not as a pack of barbarians, but as a literate people who had simply lost all their books. Likening them to castaways washed ashore with just a few of their greatest volumes, the medievals, he said, set out to rebuild their civilization. Not an easy task to be sure; for not only had they lost most of their library, but what did survive, survived by nothing other than mere chance. This is how it came to pass that while all of Aristotle was lost, parts of Plato’s Timaeus somehow made it. (Of all the works by Plato, the Timaeus might be the last one that could have been any use to the people!) It would take centuries to rebuild what was lost–and this done through Latin translations made via the Arabic translations.

I like this way of imagining the medievals; for I too have suffered a shipwreck. This happened when I was 44 and walked away from my life in Japan. I left everything behind. All my beloved clothes, pottery, furniture, gifts– you name it. Just a few choice things to put in one suitcase –with the other suitcase devoted to things I imagined my son might want. Walking away from my belongings was a lot easier than you might imagine. Indeed, I found I didn’t miss any of it. Well, except for one important thing: I missed my books beyond belief.

My lost books in Japan haunted my thoughts. So a few years ago, my astronomer and I started recreating my library.

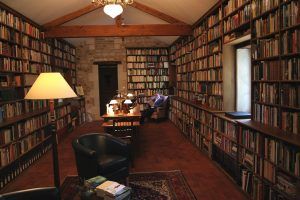

We started by building beautiful new bookcases in the house. It was pure bliss! But the more books I remembered from before the wreck, the more books we bought (it is so inexpensive to buy beautiful used books! Bliss, bliss, bliss) and here we are now with piles and piles of books. Despite having bookcases in almost every room, we still didn’t have “a library.” So, I then got the idea of turning our bedroom upstairs into a medieval scriptorium and connecting it to the adjacent kid’s room –through a portal– which we would call “the perfect library.” And, I have been planning this library in my mind for about two years now.

Fast forward to not that long ago when I was having lunch with a friend and very excitedly began describing to him the upstairs library I want to create.

Fast forward to not that long ago when I was having lunch with a friend and very excitedly began describing to him the upstairs library I want to create.

My friend, who is an Italian historian and has seen his fair share of perfect libraries, was more interested in the bedroom/scriptorium and asked me if I would have a book wheel. He says he knows a scholar back east who has a medieval book wheel in his university office and that I really must find one. I mentioned my revolving bookcases and plans to put a crucifix over the bed–but he was not impressed.

He then asked me if I had read Alberto Manguel’s Library at Night.

When I said, no, his mouth dropped open. He proceeded to tell me that Manguel was a friend to Borges and had built the most amazing library in France. Both Borges and Manguel had served as directors of the national library of Argentina, and both men loved books. But Borges –unlike Manguel–never felt the need for souvenirs of his reading and his apartment was surprisingly sparse of books. This was not so of Manguel, who as much as he loved and was a great supporter of public libraries, also gained great enjoyment from his own private collection of books. And what a collection it was; for Maguel had never suffered a shipwreck.

What does this mean?

What does this mean?

Well, it means that having never suffered a great loss of property, he now owns an uncountable number of books.

Reaching mid-life (when he wrote the Library at Night he was five years older than I am now), he decided to buy a fifteenth-century barn (which presumably had a house connected to it) in the Loire Valley. He then devoted himself to creating his perfect library. First, though, he had to rebuild the barn since it was mainly just a tilting stone wall. Local legend had it that his barn began life in earlier times as a Roman temple to Dionysius before later being transformed into a church. In time, a house was added to the property to lodge the priest. And so he comes to refer to his library as the Presbytère. (Perfect libraries must have charming names!)

Manguel turning 56, reminds us that Dostoevsky, in the novel The Idiot, had declared 56 to be the age when a person’s real life begins. The Idiot was patterned on Don Quixote. And Señor de la Mancha was also around 56 when he set out on his adventures, which were of course inspired by the reading of books in his wondrous library.

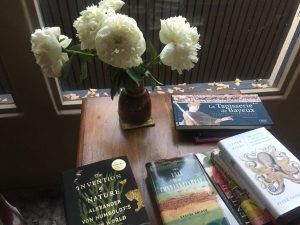

Standing on the shoulder of such giants, Manguel imagines the perfect library. In his mind, the perfect library would be a cross between the old world library of his high school, the Biblioteca del Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires, with the great long hall at Sissinghurst, in Kent England. Coincidentally, just as I was reading his book I myself had only just returned from seeing Sissinghurst, which was created by the lady aristocrat Vita Sackville-West and her husband the diplomat Harold Nicolson in the early 1930s. Taking inspiration– I assume– from her close friend Virginia Woolf in creating “a room of her own” at Sissinghurst, Vita had a glorious tower on the property filled with books. This was where she would write her wonderful articles on gardening. A tower like the great Montaigne had in the Dordogne–this tower of books is beguiling to be sure. But like Manguel, it was the library in the great hall which really grabbed my attention. Sissinghurst is famous for its gardens, and flowers could be found everywhere placed near or among the books in pretty vases. Flowers in vases, musical instruments, ceramics and globes all sat happily in this great room of books.

Mid-way into Manguel’s book, we hit the big challenge:

Mid-way into Manguel’s book, we hit the big challenge:

How to organize the perfect library?

I know, you are thinking, Duh, by subject. But there are endless possibilities for ordering a library (and thereby ordering the universe)!

Alphabetically?

For some reason that is not where I am going with this.

By geography or language?

Better.

How about by color?

My dazzlingly erudite mother-in-law (a former librarian) would have my head if I tried this– but I do like the idea. Maybe if I can get my hands on a few really great revolving bookcases I can try a color or two…

Ok, but then how about by binding?

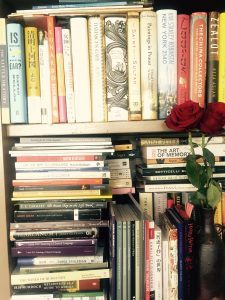

Well, I already do this (again testing my mom-in-law’s patience); for I like to keep all of my folio society books and otherwise beautifully published volumes in one particular bookcase, regardless of subject.

Another option is by date purchased.

No, that would never do.

So how about by reading priorities?

This latter is something I do already by keeping reading for any current intellectual projects piled in stacks that tower above my desk. While high priority volumes, ie, the books I frequently re-read like Borges and Umberto Eco, CS Lewis and anything relating to Jerusalem and relics in the bedroom revolving case. A word about revolving bookshelves–we have two, which are not very special, but in Japan they have wonderful sutra libraries that revolve like Tibetan prayer wheels, when pushed each revolution sending the prayers up to heaven.

This latter is something I do already by keeping reading for any current intellectual projects piled in stacks that tower above my desk. While high priority volumes, ie, the books I frequently re-read like Borges and Umberto Eco, CS Lewis and anything relating to Jerusalem and relics in the bedroom revolving case. A word about revolving bookshelves–we have two, which are not very special, but in Japan they have wonderful sutra libraries that revolve like Tibetan prayer wheels, when pushed each revolution sending the prayers up to heaven.

The more I read Manguel’s memoir the more I realized that we can discuss books and flowers until we are blue in the face, but what a library really requires is a cataloguing system.

Manguel is full of wonderful stories of ways people have organized their books. For example, there is Avicenna visiting the sultan’s library in Bukhara, where books were kept in trunks. And the only organization was that sacred books were kept separately from the rest–so that the sultan’s library was clearly divided into books by the hand of God and books by the hands of men. I think something similar took place at the Spanish library at el Escorial, with censored books kept apart (but kept from the fires of the Inquisition nonetheless). One of my own favorite methods described by Manguel was created by an eccentric 17th century British bibliophile, Sir Robert Cotton Would you believe, Cotton put all his books in twelve bookcases, each adorned with a bust of a Roman emperor? When Cotton’s library was eventually given to the British Library, his strange cataloguing system was retained; so that someone looking for the Lindisfame Gospels would be directed to: Nero D IV (namely: Nero case, 4th book on 4th shelf down!) I love to imagine that he could divide his books into Roman emperors and never grow confused! Manguel also tells of the ancient third century Chinese imperial library, which was divided by –canonical or classical texts; works of history, philosophical works, and misc literary–each bound in a specific color (with all canonical being green, history red, philosophy blue and misc grey) Isn’t that great?

My husband says all this would be impossible in a Manhattan apartment.

Well, Manguel would probably retort that–no matter what size library we are talking about–if a library is a mirror of the universe then the catalogue is a mirror of that mirror!

Well, Manguel would probably retort that–no matter what size library we are talking about–if a library is a mirror of the universe then the catalogue is a mirror of that mirror!

Does it matter where books sit next to one another on the shelves?

While playing with the idea that his library will stand as a kind of legacy of his life, long after the body of the man has turned to dust; he wonderfully tells the reader that he also “likes to imagine that, on the day after my last, my library and I will crumble together, so that even when I am no more I’ll still be with my books.” It’s true that libraries have also been mausoleums. Think of Ramses II or Alexander the Great’s places of final rest. Or el Escorial in Spain. Manguel, though, seems to reject the legacy of memory aspect to his library.

So, then, what does it all mean?

Well, like so many others who came before him, Manguel wonders if perhaps more than anything, a library is nothing more than a simple consolation –since we all know, no library can last forever, just as no human life can last forever.

As balm for the fractured soul~ this is how he ends his book.

It reminds me of the Abbey Library of St. Gall, which has above its door a plaque that reads: syches iatreion, which can be translated as “pharmacy of the soul.” This claim that books are medicine for the soul (or libraries are hospices for the sick) is, in fact, the world’s oldest library motto, dating all the way back to Pharaoh Ramses II, whose ancient library also had a “plaque” above the door designating the pharaoh’s library to be a “house of healing for the soul.”

It reminds me of the Abbey Library of St. Gall, which has above its door a plaque that reads: syches iatreion, which can be translated as “pharmacy of the soul.” This claim that books are medicine for the soul (or libraries are hospices for the sick) is, in fact, the world’s oldest library motto, dating all the way back to Pharaoh Ramses II, whose ancient library also had a “plaque” above the door designating the pharaoh’s library to be a “house of healing for the soul.”

This dream I have of building a library in my new home has brought me more happiness and pleasure than I can describe; and so often I feel like I am building a great ship of books that I can someday float away in to anywhere. But, I know that all good things must come to an end. Like Manguel (who wrote a book on the packing up of his library after events changed in his life and he could no longer keep the books together in France), I try to keep a certain detachment from my things these days–even from my beloved books. Mary Hrovat right here in these very pages, wrote so beautifully a few months ago about the consolation that books have brought into her life–and she likewise writes about the realization that nothing lasts forever. I shall end this with her words now:

My mind and my personal history are the threads binding my books into a more or less cohesive and unique whole. I don’t relish the thought of those threads someday being cut. However, I’ve picked up enough bits and pieces from libraries once held together by other minds that I can live with the thought of my books going out into the world after I’m gone. Just as my constituent molecules will be dispersed into the biosphere and eventually taken up by other living things, I hope at least some of my books will be picked up and enjoyed by other people.

**

What is your dream library? What libraries are a mirror of your mind? Here is a list of famous book hoarders. Here are some of my own favorites:

The Abbey Library at St Gall

Sissinghurst Library

Biblioteca dell’Archiginnasio, Bologna

Rotating Sutra Library at Hasedera

Oriental Library in Tokyo (for its Silk Road archives)

Hapsburg Libraries at el Escorial and the Vienna State Library

Monastery Libraries at Admont and Melk

Coimbra

Royal Library of Turin

(Why have I never seen in French libraries? And to see the library at Salamanca is a top priority!)

**

To read: Alberto Manguel: The Library at Night. And because Manguel believes paradise can never last, his recent book; Packing My Library: An Elegy and Ten Digressions

For more: see my posts on the book burning scene in Don Quixote: Don Quixote: When Professor Wey-Gómez Ate Mochi and The Inquiry of the Library

To watch: below is a trailer of the exhibition The Library at Night: virtual reality immersion into libraries, where visitors got to don headsets using 360° video immersion technology that took them on visits to 10 libraries, real or imagined. From Sarajevo’s National and University Library, magically risen from the ashes, to Mexico City’s Megabibliotheca, the stunning digital-age Biblioteca Vasconcelos; Other famous libraries included the library at Admont Abbey in Austria to the rotating library of sutra at Hasedera in Japan; and also to imaginary realms where they visited the legendary library of Alexandria at the bottom of the sea and the library aboard Captain Nemo’s Nautilus.