by Ashutosh Jogalekar

There are two kinds of science writers which I will call “artists” and “craftsmen”. Since I might face the opprobrium of both groups by attaching these labels to them, and especially because the two categories may overlap considerably, let me elaborate a little. Artists are big on literary science writing; craftsmen are big on explanatory science writing. Artists write beautiful prose; craftsmen write clear prose. Artists write relatively few books and are likely to win big book awards like the Pulitzer Prize; craftsmen are content to be merely prolific, often writing dozens or even hundreds of books.

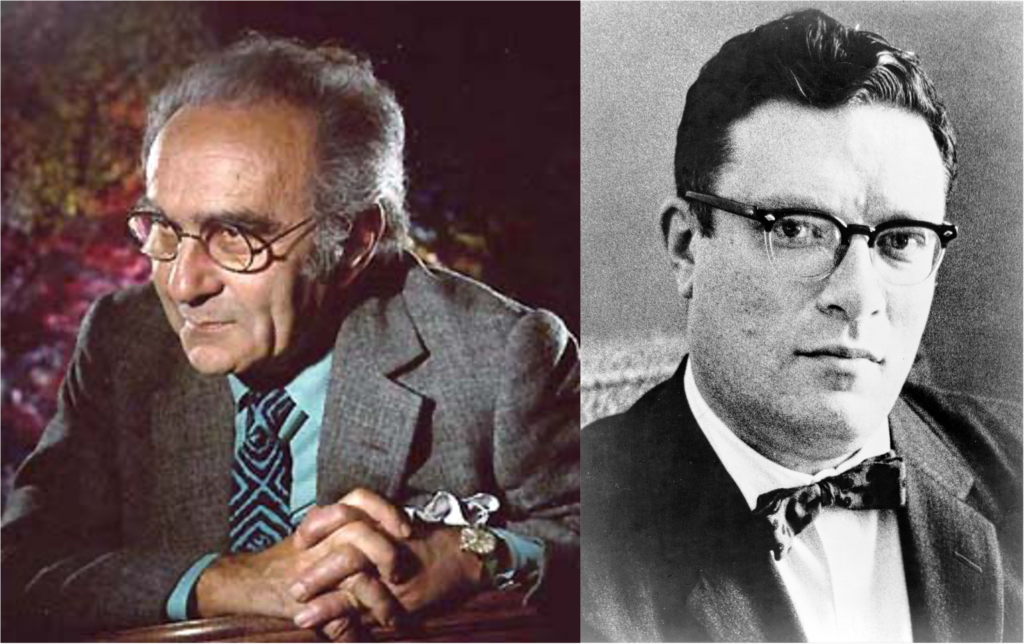

Let me quote from a master craftsman of the trade to put the discussion into context. Isaac Asimov who wrote more than 500 books, seemingly on every subject conceivable, had the following to say about his writing style:

“I made up my mind long ago to follow one cardinal rule in all my writing—to be ‘clear’. I have given up all thought of writing poetically or symbolically or experimentally, or in any of the other modes that might (if I were good enough) get me a Pulitzer prize. I would write merely clearly and in this way establish a warm relationship between myself and my readers, and the professional critics—Well, they can do whatever they wish.”

Asimov wasn’t just a great science fiction writer but a great science writer. He was known as “The Great Explainer” for his ability to explain complex, sweeping scientific topics to laypeople. But Asimov’s quote above also illustrates a central dilemma of science writing. That dilemma was best captured by the physicist Paul Dirac when he expressed puzzlement to Robert Oppenheimer who he had befriended while the two were researchers at the University of Göttingen in the 1920s. Oppenheimer, a man with broad interests across science and the humanities, studied both physics and poetry. Befuddled, Dirac once asked him, “Oppenheimer, they tell me you are writing poetry. I do not see how a man can work on the frontiers of physics and write poetry at the same time. In science you want to say something that nobody knew before, in words which everyone can understand. In poetry it seems to be the opposite”. Dirac had a point. In science a tiger is a striped mammal and an apex predator. In poetry a tiger is a “tyger”, with an “immortal hand or eye framing thy symmetry”.

On one hand, science writing is about the facts of the universe – about evolution and the Big Bang, dinosaurs and rocks, electrons and earthworms. On the other hand, it is about the human beings who do science. Any fair view of describing science, while grounded in the facts of science, also has to pay its respects to the people who do science. And each of these aspects of science deserves its own style.

A literary style doesn’t always work well for explaining the basic facts. In fact it might even obscure them. This is simply because when you are explaining complex scientific facts, you are already making the reader’s mind work overtime in understanding fairly complicated concepts – quantum mechanics, relativity, population genetics and the like. You don’t want to further burden the reader by having them wind their way through literary flourishes, metaphorical allusions and clever wordplay.

On the other hand, a style that merely explains the facts, no matter how well, doesn’t always do justice to the human side of science. Science is a human adventure. The lives of scientists are linked inextricably with the discoveries of science, and so are, often, the social and political times in which science is done (this is not some kind of extreme postmodernist spin on science – the facts don’t have a built-in human bias, but their interpretation and reception often does). All this makes for grand drama and a great story, the kind of story that can definitely benefit from a novelist’s sense of character, timing and poignant detail.

The challenge of good science writing is to blend both these styles in a way that seems seamless and smooth, which is easier said than done because the styles sound so different. It may seem like a science writer has a split personality if she combines both voices in the same volume. But it’s not as bad as it sounds. A writer in this regard isn’t too different from a person. In our lives we exhibit different personalities in different situations and with different people – we are not the same at work and home, for instance – but we move between these different personalities with aplomb, recognizing that inhabiting those multiple personalities is an essential, if seemingly paradoxical, part of being an integrated personality. With a nod to Niels Bohr, these personalities are all complementary.

Science writers have similar, complementary personalities. It’s not just strange but necessary for the science writer to wear two or more hats when writing good science. And the best ones are able to change these hats at will, making the change seem effortless. I will note three of my favorites. Richard Rhodes’s seminal history of nuclear physics and the Manhattan Project, “The Making of the Atomic Bomb” is a twin tale of great scientific developments on one hand and great historical and political developments on the other. When he is describing the history of the Jews or the human cost of the First World War or the Faustian bargain that nuclear weapons brought us, Rhodes is at his literary, artistic best. An example:

“For the scientist, at exactly the moment of discovery—that most unstable existential moment—the external world, nature itself, deeply confirms his innermost fantastic convictions. Anchored abruptly in the world, Leviathan gasping on his hook, he is saved from extreme mental disorder by the most profound affirmation of the real.”

But when he has to switch to describing the explosive lenses that compressed the plutonium in the Trinity bomb or the cyclotrons that produced uranium, Rhodes quickly puts on his craftsman hat, leading us through the ins and outs of electromagnetic separation and imploding shockwaves with clarity and precision. Here’s Rhodes describing the first split second after the bomb at Trinity exploded:

“Time: 0529:45. The firing circuit closed; the X-unit discharged; the detonators at thirty-two detonation points simultaneously fired; they ignited the outer lens shells of Composition B; the detonation waves separately bulged, encountered inclusions of Baratol, slowed, curved, turned inside out, merged to a common inward-driving sphere; the spherical detonation wave crossed into the second shell of solid fast Composition B and accelerated; hit the wall of dense uranium tamper and became a shock wave and squeezed, liquefying, moving through; hit the nickel plating of the plutonium core and squeezed, the small sphere shrinking, collapsing into itself, becoming an eyeball; the shock wave reaching the tiny initiator at the center and swirling through its designed irregularities to mix its beryllium and polonium; polonium alphas kicking neutrons free from scant atoms of beryllium: one, two, seven, nine, hardly more neutrons drilling into the surrounding plutonium to start the chain reaction.”

Another artist-craftsman is James Gleick who in his “Chaos“seems to achieve almost the perfect blend of explanatory science writing and human interest story (it is perhaps no coincidence that both “Chaos” and “The Making of the Atomic Bomb” were nominated in the same year for the Pulitzer Prize, with the latter winning). Here’s Gleick:

“The brain does not own any direct copies of stuff in the world. There is no library of forms and ideas against which to compare the images of perception. Information is stored in a plastic way, allowing fantastic juxtapositions and leaps of imagination. Some chaos exists out there, and the brain seems to have more flexibility than classical physics in finding the order in it.”

Perhaps the most remarkable artist-craftsman in my view was the late Freeman Dyson who combined good explanatory science that was lofted up high by very simple but elegant sentence structure (“You ask: what is the meaning or purpose of life? I can only answer with another question: do you think we are wise enough to read God’s mind?”). In book after book, Dyson showed his a gift for explaining complex science with a sensitive and elevated understanding of the people who do it.

There are many other writers who fall squarely into the camp of either artist or craftsman but who achieved high prominence in their worlds. Artist Jacob Bronowski wrote “The Ascent of Man“, an incredibly eloquent look at the rise of science and the profound, often painful changes it wrought in human affairs (“It is important that students bring a certain ragamuffin, barefoot irreverence to their studies; they are not here to worship what is known, but to question it.”). Artist E. O. Wilson similarly spoke with beauty and elegance about the natural world, combining science, philosophy and personal memoir in a way few others have done (“We are drowning in information, while striving for wisdom.”). In more recent generations, I admire as artists Ann Finkbeiner and Amanda Gefter, both of whom can make science sound like a great adventure and scientists like heroes, tragic or otherwise. Here’s Finkbeiner talking about the Faustian bargain that is science:

“The idea that curiosity leads to disaster has an ancient pedigree. Pandora opened the gods’ box and let loose all the evils of the world; the descendants of Noah built the Tower of Babel to reach heaven, but God scattered them and confounded their language; Icarus flew so close to the sun that his homemade wings melted, and he fell into the sea and drowned; Eve ate the apple of knowledge and was exiled from the Garden of Eden; Faust traded his soul for sorcery and spent eternity in hell. Saint Augustine, along with most medieval Christian theologians, considered curiositas a vice. The idea survived into the twentieth century about halfway intact. We believe that curiosity is the beginning of knowledge and especially of science, but we know that the application of science has led to disaster.”

And Gefter ends her tragic story of Walter Pitts and Warren McCullough, brilliant and wronged pioneers of neuroscience and computation, thus:

“On Saturday, April 21, 1969, his hand shaking with an alcoholic’s delirium tremens, Pitts sent a letter from his room at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston to McCulloch’s room down the road at the Cardiac Intensive Care Ward at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. “I understand you had a light coronary; … that you are attached to many sensors connected to panels and alarms continuously monitored by a nurse, and cannot in consequence turn over in bed. No doubt this is cybernetical. But it all makes me most abominably sad.” Pitts himself had been in the hospital for three weeks, having been admitted with liver problems and jaundice. On May 14, 1969 Walter Pitts died alone in a boarding house in Cambridge, of bleeding esophageal varices, a condition associated with cirrhosis of the liver. Four months later, McCulloch passed away, as if the existence of one without the other were simply illogical, a reverberating loop wrenched open.”

But just like with anything else, there can be too much of a good thing, and unfortunately some scientists overdo the artistic angle. Among these I have to painfully note the late Stephen Jay Gould. The Early Gould wrote superb essays on natural history which came roaring your way with a veritable avalanche of facts and literary and philosophical allusions and often with no dearth of moral suasion. But the Late Gould carried this literary surfeit so far, in my opinion, that his writing became dense and impenetrable, almost a caricature of itself. I distinctly remember a book club that I was a part of selecting Gould’s “The Hedgehog, the Fox and the Magister’s Pox”, and the members coming to the session with confused, rather pained looks on their faces.

Among craftsmen belongs John Gribbin whose “In Search of Schrödinger’s Cat” I still consider the best popular introduction to the mysteries of quantum mechanics, one which inspired my own interest in modern physics as a teenager. Gribbin’s prose is swift and certain and describes the facts and personalities without ever sounding dry. However, just like with artistry, craftsmanship can be taken so far that it no longer resembles craftsmanship. A prolific science writer I am familiar with writes prose so dry that the Atacama desert seems like a tropical rainforest in comparison.

Asimov was certainly a master craftsman, pounding out crystal clear explanations of an astonishing variety of science as fast as he could type. And a particularly inspiring example of a craftsman, but one who could also inspire artistically, was the late Steven Weinberg (“The effort to understand the universe is one of the very few things that lifts human life a little above the level of farce, and gives it some of the grace of tragedy.”). One common trait that Weinberg and Asimov shared was an impatience with shoddy thinking, an unbending insistence on rationality and a basic decency that saw every reader of their books as a worthy reader. Neither of them talked down to their readers, understanding that while they may not have been scientists, they were every bit as smart as any of their fellow scientists and science writers. They had no desire to mystify what were already complex scientific topics, and they knew that their readers would notice instantly if they did. It’s a lesson that the more literary writers should keep in mind, lest the explanatory power of their writing threaten to be overwhelmed by the beauty of their words. On the other hand, the bare-bones writers should keep in mind that science is one of the most beautiful things human beings have done, and deserves prose matching the beauty.

Does the future belong to artists or craftsmen among science writers? The history of science writing makes me feel that while both are equally important, their relative merit will largely be driven by the tenor of the times and the needs of the moment. When a new development like gene editing or quantum computing comes along, you need craftsmen who can explain it to the world at large in precise, clear detail. But when a development has been taking place for a while and we have the benefit of being able to put some distance between ourselves and all its ramifications, there is a greater need for those who can understand and communicate the human struggle and the grand picture which it signified. As long as science is being done and scientists are doing it, there will be plenty of work, and possibly employment, for both artists and craftsmen in science writing.