by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

In heaven, there will be no more sea journeys, says Virgil. For much of human history, to journey by ship across open waters was thought of almost as an act of transgression. It was something requiring great temerity and audacity. It was therefore something not to be taken lightly.

Crossing boundaries, such journeys often ended in ruin.

CS Lewis once described the people of the Middle Ages, not as a pack of barbarians, but as a literate people who had simply lost all their books. Likening them to castaways washed ashore with just a few of their greatest volumes, the medievals, he said, set out to rebuild their civilization. Not an easy task to be sure; for not only had they lost most of their library, but what did survive, survived by nothing other than mere chance. This is how it came to pass that while all of Aristotle was lost, parts of Plato’s Timaeus somehow made it. (Of all the works by Plato, the Timaeus might be the last one that could have been any use to the people!) It would take centuries to rebuild what was lost–and this done through Latin translations made via the Arabic translations.

I like this way of imagining the medievals; for I too have suffered a shipwreck. This happened when I was 44 and walked away from my life in Japan. I left everything behind. All my beloved clothes, pottery, furniture, gifts– you name it. Just a few choice things to put in one suitcase –with the other suitcase devoted to things I imagined my son might want. Walking away from my belongings was a lot easier than you might imagine. Indeed, I found I didn’t miss any of it. Well, except for one important thing: I missed my books beyond belief.

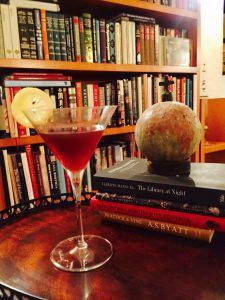

My lost books in Japan haunted my thoughts. So a few years ago, my astronomer and I started recreating my library. Read more »