by Mark Harvey

“It is not often that you see life and fiction take each other by the hand and dance.” ―Lawrence Thornton, Imagining Argentina

Watching the recent elections in Argentina makes an arm-chair economist like me face-palm myself. The country that was once one the richest in the world, the country that has an embarrassingly large assortment of riches—wheat, oil, soybeans, cattle, olives, grapes, minerals and the like–can’t get out of its own way when it comes to retaking its place as a wealthy nation.

In November, Argentina elected Javier Milei, the self-described anarcho-capitalist, as its new president. Milei has a little of everything—a dash of Brazil’s ex-president Bolsonaro, a dash of Trump, and a dash of Elon Musk. He’s like one of those fruitcakes passed around at Christmas with all the colorful little radioactive bits that you can’t quite identify.

Milei was a blasphemous candidate, calling Pope Francis—himself an Argentine– an hijo de puta (son of a bitch), calling the president of Brazil (Argentina’s second biggest trading partner) a corrupt communist and even taking a shot at Micky Mouse, comparing him “…to every Argentine politician because he is a disgusting rodent whom everybody loves.” He’s also a climate-change denier who believes the sale of human organs should be legal and even dithers on the sale of children, saying that it’s essentially context-dependent. Read more »

It seems as if everyone in the wine industry proclaims that wine tasting is subjective. Wine educators encourage consumers to trust their own palates. “There is no right or wrong when tasting wine,” I heard a salesperson say recently. “Don’t put much stock in what the critics say,” said a prominent winemaker to a large audience when discussing the aromas to be found in a wine. The point is endlessly promoted by wine writers. Wine tasting is wholly subjective. There is no right answer to what a wine tastes like and no standards of correctness for judging wine quality.

It seems as if everyone in the wine industry proclaims that wine tasting is subjective. Wine educators encourage consumers to trust their own palates. “There is no right or wrong when tasting wine,” I heard a salesperson say recently. “Don’t put much stock in what the critics say,” said a prominent winemaker to a large audience when discussing the aromas to be found in a wine. The point is endlessly promoted by wine writers. Wine tasting is wholly subjective. There is no right answer to what a wine tastes like and no standards of correctness for judging wine quality.

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing

Wine and music pairing is becoming increasingly popular, and the effectiveness of using music to enhance a wine tasting experience has received substantial empirical confirmation. (I summarized this data and the aesthetic significance of wine and music pairing  For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like. Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say. I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality. Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting  In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative. I’m sitting in front of my window on the world sipping a disappointing Cabernet Sauvignon from Napa Valley and thinking about travel plans for next summer and fall. I’m proceeding as if everything were normal knowing full well they won’t be, especially not with our “leadership”. Every time I try to write something insightful about wine, these lyrics from the bard of Duluth run through my mind:

I’m sitting in front of my window on the world sipping a disappointing Cabernet Sauvignon from Napa Valley and thinking about travel plans for next summer and fall. I’m proceeding as if everything were normal knowing full well they won’t be, especially not with our “leadership”. Every time I try to write something insightful about wine, these lyrics from the bard of Duluth run through my mind: Research by linguists

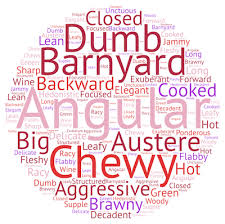

Research by linguists The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even

The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even  Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists  It’s the holiday season and time to think about presents for the budding wine lover in your life. Of course, any season is the right time to think about that. You should always support your local wine lover. One place to begin is this compelling book by long-time food critic Jon Palmer Claridge entitled

It’s the holiday season and time to think about presents for the budding wine lover in your life. Of course, any season is the right time to think about that. You should always support your local wine lover. One place to begin is this compelling book by long-time food critic Jon Palmer Claridge entitled Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.

Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.  It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation. If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry?

If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry? Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past.

Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past. It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month

It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month