by Ashutosh Jogalekar

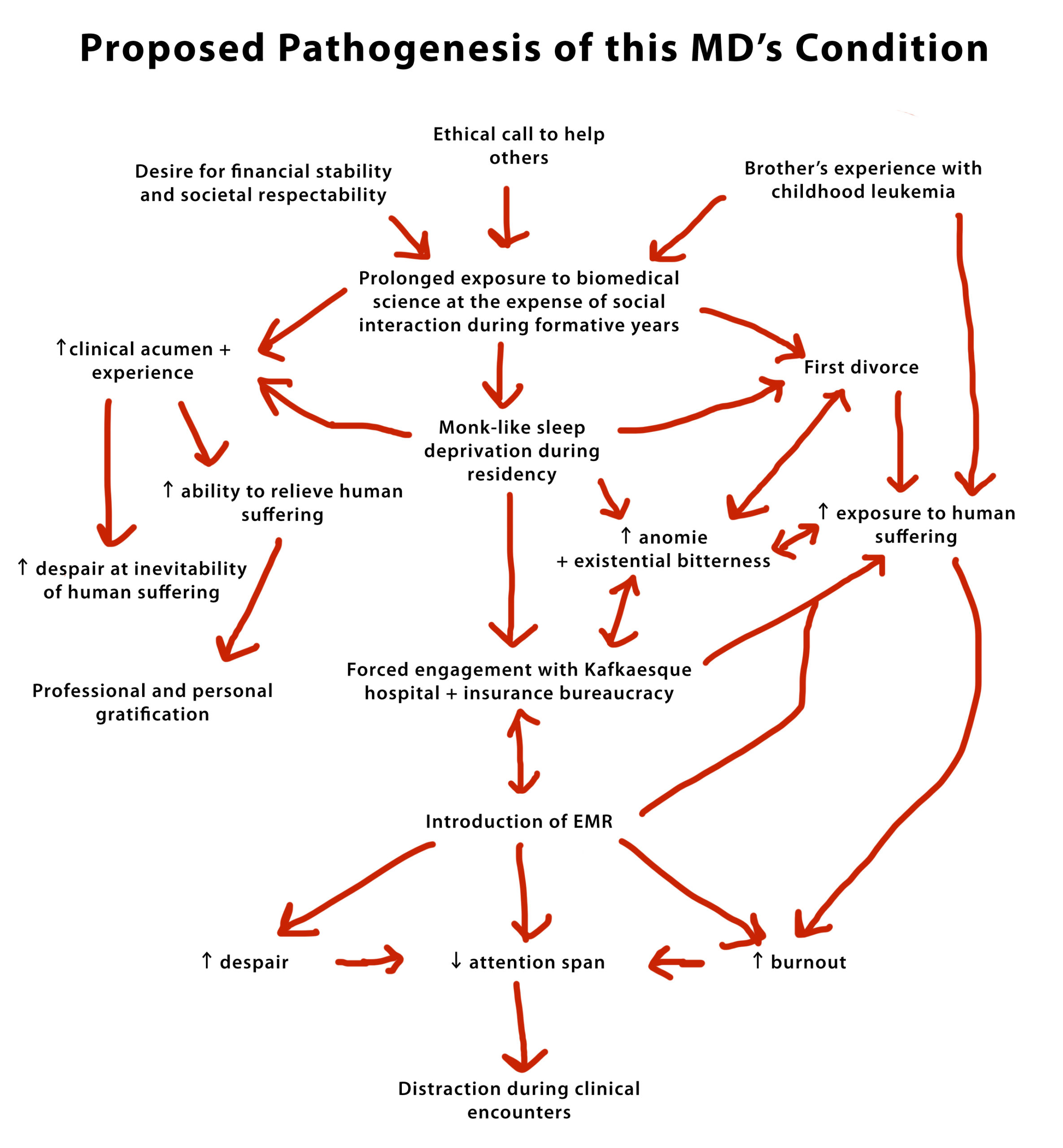

Drugs for mental illness are notoriously hard. Human biology is complex, and the brain is even more complicated. We now have a good understanding of the basic mechanisms of neurotransmission, but the drugs we have for treating disorders like depression, anxiety and psychosis are often “spray and pray” approaches, either targeting the wrong mechanisms of dysfunction or targeting too many or too few. Antidepressants often stop working. Anti-anxiety medication can do little more than sedate. And many antipsychotic drugs have prohibitive side effects.

Nevertheless, there are rare cases when genuine breakthroughs occur in the field. Thorazine famously emptied out the cruel mental asylums of the 1950s and 1960s. L-DOPA provided genuine benefits for Parkinson’s patients. And there is no denying that the new generation of antidepressants works at least occasionally for a subset of patients. Last year one such potential breakthrough seemed to fly under the radar of breathless news dominated by politics and social issues. If its promise holds up, it could herald a new kind of treatment for schizophrenia.

As is well known, schizophrenia is a serious form of psychosis that is characterized by disordered thinking, hallucinations and impaired speech and expression. The disease profoundly impacts the quality of life of afflicted individuals, including being able to sustain social relationships and professional goals. In severe cases, as made infamous by the case of Michael Laudor, even high-functioning schizophrenics can become a fatal threat to themselves or others. Estimates of the prevalence of schizophrenia in the United States range from 0.25%-0.64%.

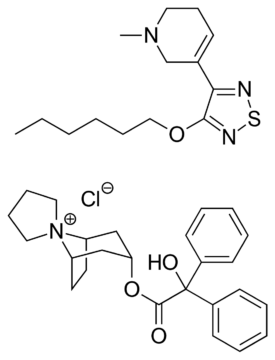

All drugs work by blocking or improving the function of proteins or receptors. Receptors in the brain include those that regulate the function of neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine. Neuropharmacological drug discovery starts with identifying these receptors and then discovering molecules that selectively inhibit or activate them. For instance, most antidepressants are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) which increase the concentration of serotonin by blocking its re-absorbption and improving a sense of well-being. Read more »

A few days ago I finished watching a new

A few days ago I finished watching a new