by Scott Samuelson

When we conjure up what thinking looks like, what tends to leap to mind is an a-ha lightbulb or a brow-furrowed chin scratch—or the sculpture The Thinker. While there’s something deservedly iconic about how Rodin depicts a powerful body redirecting its energies inward, I think that the most insightful depictions of thinking in the history of art are found in the work of Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652), a.k.a. José de Ribera or Lo Spagnoletto (The Little Spaniard). In a time when we’re alternatively fascinated and horrified by what artificial intelligence can do, even to the point of wondering whether AIs can think or be treated like people, it’s worth asking some great Baroque paintings to remind us of what natural intelligence is.

Early in his artistic career, Ribera went to Rome and painted a series on the senses. Only four of the original five paintings survive (we suffer Hearing loss). Touch, the most interesting of the remaining paintings, depicting a blind man feeling the face of a sculpture, launches a crucial theme throughout Ribera’s work.

Let’s try to imagine Ribera in the process of making this painting. He looks at live models, probably at an actual blind man. He studies prints, sketches, fusses with his paints, maybe takes a walk. He sleeps on it. He chats with a friend and lights on an approach: a blind man exploring a sculpture by feeling it. He hurries back to his studio and begins to paint. He notices more about his subject, makes a mistake, fixes it. He holds up a jar of paint—no, that one would be better. Somewhere in this process, I imagine, it dawns on him that he’s doing the same thing as the blind man. (Maybe this is why he decides to put the painting on the table—though the painting is also a powerful visual reminder for us that there are always limits to our engagement with the world.)

Regardless of what actually went through Ribera’s head, the point I’m trying to make has been illustrated—both figuratively and literally—by a contemporary artist. In the 1990s Claude Heath was sick of the ideas of beauty that governed his artistic work. So, he lit on the idea of drawing a plaster cast of his brother’s head—blindfolded. Using small pieces of Blu-tack for orientation, one stuck into the top of the cast, one into his piece of paper, he felt the head’s contours with his left hand and drew corresponding lines with his right. “I tried not to draw what I know, but what I feel . . . I created a triangle, if you like, between me, the object, and the drawing . . . It was a bit of a transcription.” He didn’t look at what he was doing until he was finished. By liberating himself from ideas of beauty, he made beautiful drawings.

In a loose sense, Heath’s drawings could serve as the blind man’s thought bubble while he touches the sculpture to make sense of it. But Heath’s drawings aren’t representations of thinking. They are his thinking. There’s no thought bubble with a tangle of lines floating above his head. Thinking is the living triangle formed by the plaster cast, Claude Heath, and his fountain pen. In fact, Heath’s blindfold drawings are closer to portraying what Ribera was thinking than what his blind subject was thinking.

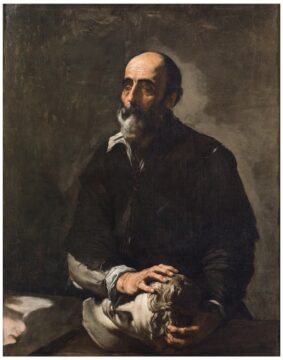

We know that Ribera was fascinated by the living triangle formed by the unknown world, the opened-up senses, and the engaged mind, because he returns to what he stumbled on in his early painting. In 1632, he does an even more powerful version of Touch. In the first version, a middle-aged blind man urgently feels the face of the sculpture. In the second, a balding blind man leisurely explores—almost massages—the sculpture’s locks of hair.

The artist’s sense of what mental life looks like has become so fine-tuned he shows it in the smallest gestures. Though the blind man’s face is slackened, his eyebrows register his thoughts with the precision of a seismograph. It’s like Ribera is boasting, “I can portray thinking in the tension of a pinky finger or a single wrinkle on a forehead.”

The vertical distance Ribera places between the blind man’s face and hands—a striking compositional change from the first Touch—aids in communicating the thought-work of the blind man. As viewers, we look down at the hands and then up, up, up to the rumpling eyebrows—or up at the face and then down, down, down to the fervent fingers. In forcing our eyes to make the physical back-and-forth journey of the blind man’s mental translation of the statue, Ribera has found a way of showing us how our reading of the painting is another act of the tingling triangle of thinking.

Shortly after completing this later Touch, Ribera is commissioned to paint a series of ancient philosophers. How should he depict thinking when it’s not directly registering the world through the senses? How do you show thinking itself? Inspired by Caravaggio’s use of working-class models, he portrays the thinkers as gritty Romans in tattered clothes. Didn’t the likes of Diogenes disdain pomp and riches? Even more interestingly, all six of the philosophers he paints are holding a book, but only one is reading. The others are thinking—and just happen to be in contact with a book. For instance, Aristotle holds a shut book with his right hand and tenderly touches writing paper with his left as his shadowy eyes gaze into the darkness. Looking beyond the discourses in the book, he refocuses himself on what hasn’t yet been written or understood.

In all the paintings, an investigative touching of things is shown to be internalized by the philosophers. While their minds gather evidence and feel out possibilities and grasp ideas, their hands go on unconsciously making residual motions of exploration, designation, stimulation. They may be lost in thought, but they’re not off in la-la land. Like the blind man with his sculpture, they’re desperately trying to make sense of the world. In The Visible and the Invisible, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose twentieth-century phenomenology resonates with Ribera’s seventeenth-century paintings, makes a similar point in arguing that philosophy is “the simultaneous experience of the holding and the held in all orders.”

In his earlier paintings, Ribera discovered that the work of the senses is already a thoughtful exploration of a yet-to-be-known reality. Now he sees that the work of even the most abstract kind of thinking is an internalization of that sensual exploration, a redeploying of it into invisible (or at least not immediately obvious) levels of reality. When we’re thinking about what we really believe or have to say, we’re doing something like the blind man’s touch-exploring of a sculpture. We’re gathering ourselves inward and launching ourselves into the unknown to translate it into something meaningful. Our senses are raised to the level of making sense.

Given the aliveness of Ribera’s painting of grizzled hands and dirty fingernails, I wonder if his choice of working-class models doesn’t take on a special significance. Whereas his Renaissance predecessors, like Raphael in the School of Athens, elevate painting from a mere craft to a liberal art on par with astronomy or philosophy, Ribera scrambles the whole hierarchy. Craft isn’t merely a craft. Philosophy is a kind of craft, and craft is a kind of thinking. They’re different ways of playing with the angles of the living triangle formed by our hands, our head, and the vast book of the world.

All the most vital kinds of human engagement involve a “raid on the inarticulate,” to use T.S. Eliot’s description of his poetry. By contrast, artificial intelligence can be quite accurately described as a raid on the already articulated. Even when generating new content, it’s doing so within the contours of the known. Sure, we do that too. We often treat the world as mere input and raid our established discourses to reproduce what we’re supposed to be thinking, saying, doing, or making (like what Heath was originally doing that so frustrated him: trying to back his art into a preestablished idea of beauty). But thinking in its active state isn’t simply getting input and reprocessing it according to algorithms. The most vital kind of engagement happens when we start with the unknown and actively translate it into another register (like Heath blind-drawing the plaster cast). The hallmark of this kind of thinking is the experience of not realizing what you really think until after you express it. This is the essence of the free mind.

The creative arts, philosophy, and scientific exploration are the most powerful modes of what I’m talking about, but we all have experiences of it—for instance, in having a thought-provoking conversation, writing a meaningful letter, close-reading a great book (or some great paintings), or practicing a craft like cooking where we taste our way to a surprising deliciousness. If LLMs aren’t to make us completely shallow and manipulable, we should recommit to these practices of making, reading, fixing, and thinking. As the virtual becomes a world unto itself, it’s more important than ever to retriangulate our relationship to reality—not just so we can productively use AI and adequately judge its products but so we can lead meaningful lives enriched by an engagement with the mind-blowing.

Fundamentally, Ribera reminds us that thinking is something done by biological beings with hands and stomachs and fragile flesh. Our rationality is deep-rooted in our interactive relationship to the vast ecologies that sustain us. To confront this fact about ourselves is to confront our vulnerability and mortality. Thus, in his later work, he takes the blind man’s raid on the unseen and the philosopher’s raid on the invisible to its deepest level. Ribera produces painting after painting of St. Jerome, the most powerful of which pictures the emaciated saint holding not a sculpted head but a skull, meditating on death.

***

Scott Samuelson holds a joint appointment at Iowa State University in Philosophy & Religious Studies and Extension & Outreach. He’s the author of three books: Rome as a Guide to the Good Life, Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering, and The Deepest Human Life—all published by the University of Chicago Press.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.