by Jochen Szangolies

When the Luddites smashed automatic looms in protest, what they saw threatened was their livelihoods: work that had required the attention of a seasoned artisan could now be performed by much lower-skilled workers, making them more easily replaceable and thus without leverage to push back against deteriorating working conditions. Today, many employees find themselves worrying about the prospect of being replaced by AI ‘agents’ capable of both producing and ingesting large volumes of textual data in negligible time.

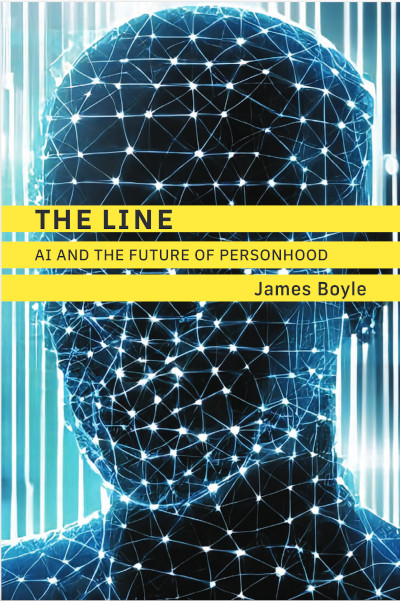

But the threat of AI is not ‘merely’ that of cheap labor. As depicted in cautionary tales such as The Terminator or Matrix, many perceive the true risk of AI to be that of rising up against its creators to dominate or enslave them. While there might be a bit of transference going on here, certainly there is ample reason for caution in contemplating the creation of an intelligence equal to or greater than our own—especially if it at the same time might lack many of our weaknesses, such as requiring a physical body or being tied to a single location.

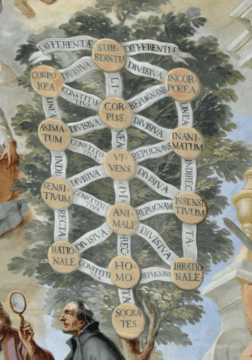

Besides these two, there is another, less often remarked upon, threat to what singer-songwriter Nick Cave has called ‘the soul of the world’: art as a means to take human strife and from it craft meaning, focusing instead on the finished end product as commodity. Art is born in the artist’s struggle with the world, and this struggle gives it meaning; the ‘promise’ of generative AI is to leapfrog all of the troublesome uncertainty and strife, leaving us only with the husk of the finished product.

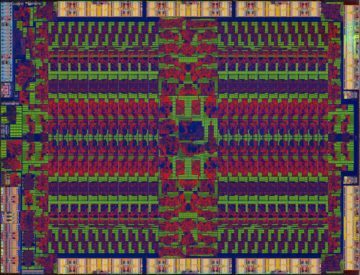

I believe these two issues are deeply connected: to put it bluntly, we will not solve the problem of AI alignment without giving it a soul. The ‘soul’ I am referring to here is not an ethereal substance or animating power, but simply the ability to take creative action in the world, to originate something genuinely creatively novel—true agency, which is something all current AI lacks. Meaningful choice is a precondition to both originating novel works of art and to becoming an authentic moral subject. AI alignment can’t be solved by a fixed code of moral axioms, simply because action is not determined by rational deduction, but is compelled by the affect of actually experiencing a given situation. Let’s try to unpack this. Read more »

‘

‘

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.![Henri Matisse created many paintings titled 'The Conversation'. This, from 2012, is of the artist with his wife, Amélie. [Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia].](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Matisse_Conversation-360x292.jpg)