by Richard Farr

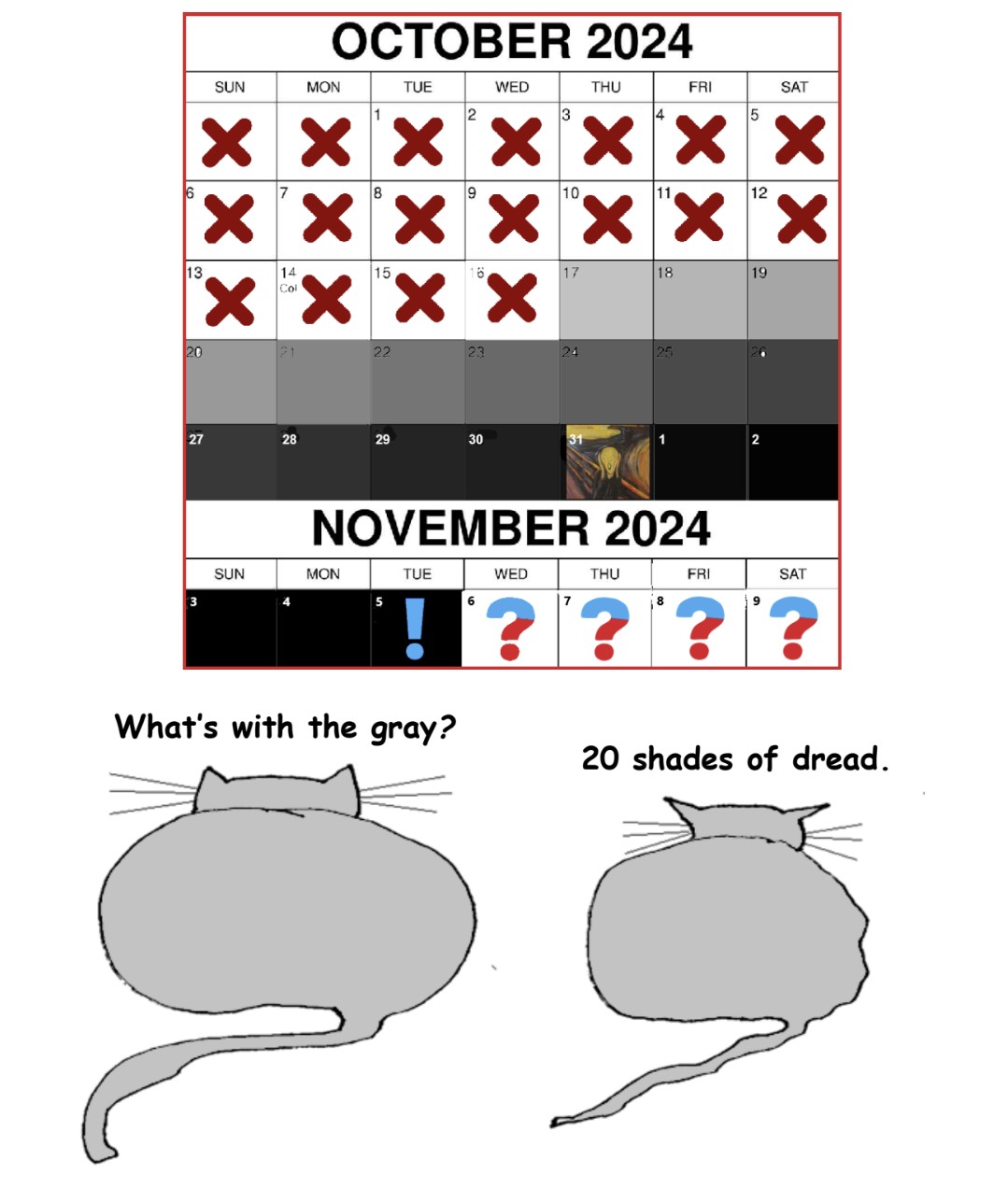

For several weeks I’ve had an article by the excellent Rick Perlstein squatting unread in my Ought-To-Read list. The title is Everything You Wanted to Know About World War III but Were Afraid to Ask. I am afraid to ask: although I ought to want to know, right now I don’t. “The world is too much with us”: unlike Wordsworth, but like you perhaps, I read the latest every day about Gaza, the Ukraine, South Sudan, the West Antarctic ice sheet, and another poll reminding me that tens of millions of my fellow citizens think a poisonous thug with a criminal record will make America great again. Sometimes you just have to switch off and leave the world behind. Even if you’d feel guilty being reminded that you haven’t been paying attention to Syria, Venezuela, the Rohingya, the Uyghurs, the women of Afghanistan, the children working in cobalt mines in the DRC, or the disturbing fact that people are actually out there buying Boris Johnson’s memoirs.

I was thinking about this reality-fatigue recently while struggling to finish a different book. Look on the bright side: I’m not going to bore you with an account of the experience, which I have fairly often, of picking up a novel that has been declared “plangent” and “luminous” (or, that champion among meaningless back cover standbys, “fiercely original”) and feeling embarrassed that I don’t get what the fuss is about. No, I’m going to address something more important than that: the experience of trying to read an excellent book, and feeling embarrassed that I barely had the moral fortitude to work through its contents.

Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs. You have to get a long way in before you uncover the source of the title, but it’s worth the wait. The subject is 9/11, tangentially. But really the subject is our crimes, our brutalities, our layer cake of madnesses and delusions in the wake of 9/11. The battalion upon red-smeared gray battalion of ugly details we either chose not to learn, or chose to forget, or chose to swallow our government’s lies about. All that — and it’s about the uses and abuses, especially in the Land of Liberty, of virtually limitless surveillance.

Not to be outdone by her own title, Kerry Howley has invented in this book what as far as I can see is an entirely original style of writing in the genre of investigative journalism. We think we know what this kind of thing is supposed to sound like, and it’s not supposed to sound like someone responding to a bad hangover by having a panic attack and then swallowing a handful of amphetamines. But Howley’s sometimes hallucinatory style is a revelation: finally, here’s a voice that suits and perfectly illuminates the material. Read more »

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase.

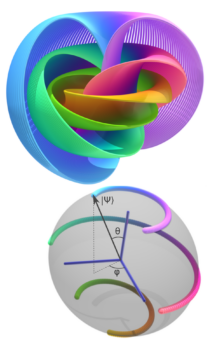

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase. Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude.

Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude. The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

Egypt

Egypt Germany

Germany

In her provocative, genre-defying book,

In her provocative, genre-defying book,

There is a

There is a  Drug overdose deaths have more than doubled in America in the past 10 years, mainly due to the appearance of Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. These drugs combine incredible ease of manufacture with potency in tiny amounts and dangerousness (the tiniest miscalculation in dosage makes them deadly).

Drug overdose deaths have more than doubled in America in the past 10 years, mainly due to the appearance of Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. These drugs combine incredible ease of manufacture with potency in tiny amounts and dangerousness (the tiniest miscalculation in dosage makes them deadly).