by Barry Goldman

The New York Times had a piece recently about a clever hustle called station flipping. It involves Citi Bikes, the blue rental bikes you see all over New York City. It seems the natural movement of people and bikes around the city results in periodic imbalances. Sometimes there are too many bikes in a docking station, other times there are too few. So Lyft, the company that owns Citi Bike, implemented a program that rewarded people for moving bikes from one station to another to correct those imbalances. The miracle of modern information technology enabled the company to track the location of its bikes with precision and to tweak the reward structure in real time. The system awarded points, and the points could be redeemed for cash. Moving a bike from a full docking station to an empty one could earn a “Bike Angel” up to $4.80.

People respond to incentives. They also, in every system everywhere, “work the points.” As a direct and inevitable result, people figured out how to game the Bike Angel system. They realized they didn’t have to wait for the natural movement of bikes and people to create shortages and surpluses, they could manufacture them.

The algorithm updated every 15 minutes. Some docking stations are only a block apart. That means a group of aerobically fit Angels can empty one docking station and fill another by riding bikes to the empty station and running back to the full station until the conditions are reversed. If they can do this before the system updates, they can earn the maximum for each ride. Then, when the full station is empty and the empty station is full, they can reverse the process and do it again. Before too long some enterprising Bike Angels were earning up to $6,000 a month.

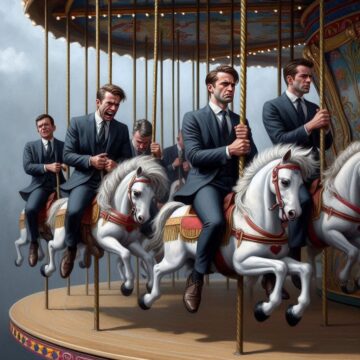

The company, predictably, was not amused. It says station flipping distorts the market and games the system. That’s pretty rich coming from Lyft, since its whole business model depends on gaming the system and distorting the market by fudging the distinction between employees and independent contractors. But that’s a different article. In this article I want to point out how station flipping maps the essential features of our financial sector.

A while back I read Other People’s Money: The Real Business of Finance by John Kay (2015) and The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer by Nicholas Shaxson (2018). I often read with a pad of sticky notes close at hand. The pointless merry-go-round of station flipping sounded familiar. So I went back and checked. Here are a few passages I had marked in Kay:

The value of daily foreign exchange transactions is almost a hundred times the value of daily international trade in goods and services. Fedwire, the payments mechanism operated by the US Federal Reserve System, processes more than $2 trillion of transfers every day, about fifty times the US national income.

Much of the growth of the finance sector represents not the creation of new wealth but the sector’s appropriation of wealth created elsewhere in the economy, mostly for the benefit of some of the people who work in the financial sector.

[F]inancialization has created a world of people who talk to each other and trade with each other, operate in a reality of their own creation, reward themselves generously for genuine if largely useless skills and yet have less to offer the real needs of the real economy than their less talented predecessors.

The finance sector spends more on lobbying than any other industry. There are about 2,000 registered finance industry lobbyists in Washington: about four for each member of Congress.

If London casinos were even accused of the malpractices to which London banks have admitted – false reporting, misleading customers, and unauthorized trading – the individuals responsible would be barred from the industry and the licenses of the institutions concerned revoked within hours.

In the most extreme manifestation of a sector that has lost sight of its purposes, some of the finest mathematical and scientific minds on the planet are employed to devise algorithms for computerized trading in securities that exploit the weaknesses of other algorithms for computerized trading in securities.

And here are a few passages from Shaxson:

In the era of financialization, the corporate bosses and their advisers, and the financial sector, have moved away from creating wealth for the economy, and towards extracting wealth from the economy, using financial techniques. Financialization has unleashed gushers of profits for the owners and bosses of these firms, while the underlying economy – the place where most of us live and work – has stagnated.

Finance literally bids rocket scientists away from the satellite industry. The result is that people who might have become scientists, who in another age dreamt of curing cancer and flying people to Mars, today dream of becoming hedge fund managers.

Inequality caused by wealth extraction is especially dangerous and divisive. That’s not just because the poor and middle classes feel increasingly left out, and have less and less to lose, but also because the billionaire classes need to distract us away from focusing on how they got rich. So they revert to the old political formula: using their control over the media to direct popular fury in other directions, towards people with the wrong skin color or the wrong sexual orientation, or from the wrong religious groups. The world has seen this hate-filled formula before.

So, let’s review. The financial economy is not the real economy. The big money isn’t in the world of goods and services, even banking services. It’s in things like STIRT, short term interest rate trading, that have almost nothing to do with the real world. The fantastic sums paid to the winners in that world have to come from somewhere. They are extracted from the real economy. And when the financial world collapses periodically from its own weight and its own contradictions, money from the real world is used to prop it up. Why? Because, as Dylan said, “money doesn’t talk, it screams.” It corrupts our politics, distorts our economy, diverts our talent, and corrodes our society.

But at least it’s a lot of fun for the Masters of the Universe who make all those millions, right? Well no, actually, it doesn’t look like any fun at all.

I’ve also been reading The Trading Game: A Confession by Gary Stevenson (2024). Stevenson was a STIRT trader at Citigroup who made multiple millions and retired at 27. He’s certainly smart, and he can write. His memoir is compelling. But the life it describes is utterly and completely joyless.

Flipping stations and scamming Citi Bike is no more useful than trading short term interest rates, and it pays far less, but it sounds like a lot more fun.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.