by Thomas R. Wells

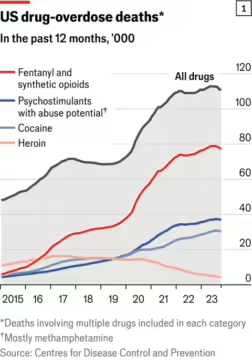

Drug overdose deaths have more than doubled in America in the past 10 years, mainly due to the appearance of Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. These drugs combine incredible ease of manufacture with potency in tiny amounts and dangerousness (the tiniest miscalculation in dosage makes them deadly).

Drug overdose deaths have more than doubled in America in the past 10 years, mainly due to the appearance of Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. These drugs combine incredible ease of manufacture with potency in tiny amounts and dangerousness (the tiniest miscalculation in dosage makes them deadly).

This continues a general and no longer surprising trend. The global war on drugs has produced a strong selection effect for drugs which are easy to manufacture and smuggle but at the cost of being much more dangerous for consumers. There is no reason to expect this trend to alter. Moreover, Fentanyl leaks – it appears as an additive in all sorts of other illegally bought drugs, like Xanax, surprising and killing consumers who had no idea what they were getting.

The best thing we can do about this – and hence the right thing to do – is to legalise all hard drugs so that consumers have a real choice about the dangers they subject themselves to.

1. Making Drugs Illegal Makes Them Much More Dangerous

The justification for banning certain drugs ultimately rests on a calculation of consequences. When very addictive, very dangerous drugs were legal – as heroin and cocaine were in most of the world in the late 19th century to early 20th century – one sees a great deal of suffering among vulnerable people and those who have to live with or amongst them. When they were banned starting around 100 years ago, that particular harm went down (though never disappeared) as would be drug consumers had to expend a lot more effort and money to obtain psychoactive substances. But on the other side of the ledger new harms were created, including invasive, racialised policing; the stigmatisation and incarceration of drug users (‘for their safety’); and gang violence in consumer and producer countries.

There has been a decades long argument about whether the harms created by the war on drugs outweighed the harms averted (often involving an implicit, disgracefully racialised argument about whose harms should count for how much). But at this point there can no longer be any reasonable doubt about where the cost-benefit analysis points. Making hard drugs illegal no longer has much of any effect in preventing the most dangerous kinds from appearing in our communities and killing people in huge numbers. In fact it makes illegally obtained drugs orders of magnitude more dangerous than they would otherwise be. If a society wants to protect people from drugs, the best thing it can do is end the war on drugs.

There has been a decades long argument about whether the harms created by the war on drugs outweighed the harms averted (often involving an implicit, disgracefully racialised argument about whose harms should count for how much). But at this point there can no longer be any reasonable doubt about where the cost-benefit analysis points. Making hard drugs illegal no longer has much of any effect in preventing the most dangerous kinds from appearing in our communities and killing people in huge numbers. In fact it makes illegally obtained drugs orders of magnitude more dangerous than they would otherwise be. If a society wants to protect people from drugs, the best thing it can do is end the war on drugs.

Making drugs and everything connected with their manufacture and sale illegal raises the financial costs of producing them, and hence of consuming them. In particular it limits the capital producers can employ. It forces them to adopt small-scale artisanal manufacturing that is easier to hide and not a big deal anyway if lost to a police raid, and limits their pool of potential employees to the kind of messed up losers who can’t keep any kind of normal job. It also raises the cost of consuming drugs in other ways, as consumers must risk their social status as law-abiding citizens and the privileges (such as employment and freedom) that come with that. To the extent that demand for drugs is price elastic, consumers will respond to those higher costs by consuming less.

However, the key feature of markets – the reason capitalism beat centrally planned socialism so emphatically – is that they are dynamic. Price changes offer signals and incentives to economic actors to act on. In the case of drugs, producers have an incentive to find ways to increase output and lower their costs while remaining hidden from the police, and this has led them to focus on the kinds of drugs that are easy to smuggle or simple for amateur chemists in a shed to manufacture from easily procured ingredients. Unfortunately for drug consumers, this selection effect generally produces drug varieties that are far more dangerous than they need to be, such as fentanyl instead of oxycontin; crack cocaine rather than the powder form; or P2P rather than ephedrine-based crystal meth. It also drives drug users to consume the same drugs in more dangerous ways (such as injecting rather than smoking them). This is what has brought us to the current situation of extraordinary and unnecessary danger for drug consumers.

People want to get high, but they generally don’t want to die. Unfortunately an illegal market lacks the ability and incentives to respond to consumers’ interest in safety. Process quality control, supply chain management, branding, legal liability and so on that are available to legal businesses to guarantee product safety are blocked directly or indirectly by having to operate illegally. Instead the war on drugs forces customers to choose between their two interests in getting high and staying safe, with the tragic results we can all see.

But there is no good reason why drug consumers should not be able to get high and stay safe. (Or at least, no good reason they should have to gamble with additional risks to their health beyond what their drug of choice already poses.) Alcohol is a powerful and dangerous drug and its misuse causes a great deal of suffering and death around the world. But at least those consuming it don’t have to worry that they might be drinking poison (in most countries). This is because there is a legal market for alcohol which incentivises producers to ensure their products are exactly what they say they are, and holds them legally accountable for any failures in their supply chains.

When extended to hard drugs the logic of the market also suggests that legal companies would also have an incentive to develop new variants of drugs which satisfy consumers’ desires for certain psychoactive effects while minimising undesired health impacts. Pharmaceutical companies can deploy orders of magnitude more financial and human capital to the challenges of competing with each other to sell more of their products. Instead of getting synthetic drugs that are far more dangerous than cocaine and heroin, we would get drugs whose intended effects are more attractive to consumers and with fewer and lesser unwanted side-effects. Those drugs would also be much cheaper (so long as the tax and regulatory regime is more sensible than California’s treatment of legal marijuana has been) because legal companies can invest in very large scale production lines, like they have for aspirin. Hence, would be drug consumers should have little interest in the toxic crap being peddled by any remaining criminal enterprises, which would be outcompeted in quality and price in a free market for drugs. As a bonus, consumer societies would also save a vast amount of tax money from their policing and prison budgets, while supplier countries would see a major source of social instability removed, and outlaw regimes like N. Korea and Syria would have to find another source of income.

It should be acknowledged that expanding the safe legal market for hard drugs so dramatically will result in an increase in drug consumption as the costs of consumption fall. When dangerous and addictive drugs become easier and cheaper to buy more people are likely to try them, whether for fun or to self-medicate against the pain in their lives in an ultimately self-defeating way. (America’s experience with oxycontin gives a glimpse of how wrong that can go.) So legalising all hard drugs would cause them to reach new people than they currently do, with the implication that the total number of people suffering from drug-abuse related problems will rise.

However, an expansion of drug-users does not necessarily indicate an expansion of drug-use related suffering.

First, it is not clear how many new problematic drug-users would be created by legalisation. I started my analysis by noting the utter failure of the war on drugs to prevent incredibly dangerous hard drugs from reaching everywhere – including inside super-controlled environments like prisons. An implication of this fact is that just about everyone who wants to use hard drugs to self-medicate against the pain in their lives is already doing so. Hence, even utterly destitute homeless people can manage to be high most of the time. Some people who are not losing hard at the game of life may also try drugs once they are legal and become losers as a result, but the evidence seems to be that most people with something to live for do not fall so easily into addiction, and are more able to pull themselves out of it.

Second, any possible new suffering caused by ending the war on drugs must be set against the vast suffering that it definitely creates. Policy choices are limited to what is possible. The choice faced by society is not how to design an ideal world and whether hard drugs would be part of that. We only get to choose between policies that lead to worlds that are flawed in different ways. It seems to me that a world in which more people use hard drugs but far fewer die from them is obviously far better than the world we have now in which so many lives are cruelly cut short.

The key question is not whether a world of legalised hard drugs would be a great place to live, but whether it would be a better world – more survivable for more people – than the world where we pretend that our efforts to ban those drugs are working. In the absence of a better option, we should support the best we can do, however imperfect.

Third, there is another difference between the worlds in which drugs are legalised and banned that is not about the number of lives lost but why they are lost. As long as hard drugs are illegal the government is – in our name – preventing people from making their own risk-benefit calculations and thus preventing them from taking responsibility for their own safety. There is a difference between people dying because they knowingly but foolishly take significant risks with their lives and us as a society forcing them to take such risks because we have made it incredibly dangerous for them to medicate themselves against the psychological stresses our society inflicts on them, while unironically claiming that we are doing this ‘for their own safety’.

II Beyond Decriminalisation; Beyond the Market

What exact form of drug legalisation would be best – which if any drugs should be excluded; how producers and retailers should be regulated and taxed; consumer age restrictions; and so forth – should be informed by specific empirical evidence as well as local conditions and political circumstances. So I leave it aside. But I do want to emphasise that legalisation is quite distinct from decriminalisation, which has been tried in various places with some success (such as Portugal from 2001) and more recently with great failure (e.g. Oregon from 2020).

Decriminalisation is not legalisation. It is merely a localised harm-reduction policy within a general war on drugs approach that attempts to capture more of the gains of criminalising drugs with fewer social costs. In the more successful cases, a public health health approach is taken to drug use rather than a criminal justice one. Not only is possession of hard drugs for personal use no longer treated as a crime, but it is treated as an opportunity for treatment. Additional harm-reduction measures such as safe injection sites with free clean needles and drug quality testing are often included. Within its self-imposed constraints, decriminalisation is a generally good idea (although it demands a lot of sustained government attention and competence to succeed). However, it fails dramatically in the new fentanyl era exactly because it is a fundamentally limited approach to the problem of dangerous drugs.

In particular, decriminalisation leaves the supply side in the hands of criminals and leaves untouched their economic incentives to focus on manufacturing drug variants in ways that evade the police or don’t matter much when lost to the police (the kinds that can be made in a shed by amateurs from ingredients easy to get hold of). Hence hard drugs remain horrifically dangerous. In addition, decriminalisation doesn’t provide the positive incentives and resources for suppliers to make drug variants that are safer and contain only the exact ingredients in the exact amounts that customers want to buy.

Although I believe that we cannot address the dangers of hard drugs without radical legalisation, I do not claim that it is enough in itself. The market is not magic. There is still an important role for government.

The capitalist incentives I count on to motivate legal companies to produce better and safer drugs than criminals do are themselves quite limited. Fast food, alcohol, and tobacco companies can also all be counted on to ensure the purity and reliability of their products, but those products are still rather bad for people, and the companies’ interest is in selling as much of them as possible, not maximising the long-term health of their customers. Some other agent is required to look out for those interests, and for example regulate drug advertising and fund accessible treatment programmes for those who find their lives disordered by their drug use. This is the proper role of government, especially of a government that claims to care about the welfare of the people under its control. It would also be good if we could somehow arrange things so that fewer people in our stunningly rich societies have lives so bad that they seek out drugs as a solution to their problems in the first place.

Thomas Wells teaches philosophy in the Netherlands and blogs at The Philosopher’s Beard

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.