by Gary Borjesson

Become what you are, having learned what that is. —Pindar

[To protect their privacy, I have changed identifying details of those mentioned here.]

What do we want for our lives? It’s a peculiarly human question; other animals don’t appear to be worrying about it. I’ve asked myself this question, sometimes with curiosity, sometimes more desperately, for as long as I can remember. I’m always moved when patients raise it in their therapy. A man who retired from a successful career said that when he looks into the future without the mantle of his professional title and status, he feels empty and lost, ashamed that at 70 he doesn’t know what he wants.

Sometimes we raise the question ourselves; sometimes the world raises it for us. Another patient, whose boyfriend just “dumped” her, is wrestling with her alcohol use. The men she wants in her life don’t want an alcoholic in theirs. She’s angry at the thought of sobering up for someone else, “Wouldn’t that be inauthentic?” At the same time, she (authentically) wants a partner in her life.

She knows what most of us know, that we want to be authentic. By “authenticity” I mean living in a way that is true to oneself and to one’s situation in the world. (For the bigger philosophic picture, see my previous column, Reclaiming Authenticity as an Ethical Ideal.) Authenticity resonates because it is that rare thing, an ideal that most of us embrace—despite our divergent religious, ethnic, social, and political values. After all, each of us faces (or not) the question of how to become our best selves.

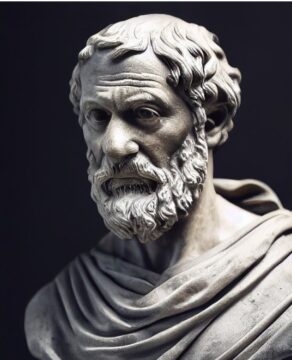

Although we must ask and answer that question for ourselves, I will suggest a few core principles that can guide our way. I’ll start with Aristotle’s view, that the one thing we all want from life is to flourish, which means living in such a way as to be fulfilling our nature. This might sound about as helpful as telling someone who is struggling, “Just be true to yourself!” How do we even know what our true self is? If we’re a lonely alcoholic, is our true self more of the same, or is it sober and in a relationship?

We can find some guidance by unpacking two principles of flourishing that extend to living authentically. The first is that flourishing describes a characteristic way of living in the world. Aristotle compares the idea of flourishing to health. Just as we call ourselves healthy even when we’ve got a cold, so we can be flourishing and living authentically even when we’re having a bad day, or not feeling particularly true to ourselves. Like other ethical virtues, such as being courageous or generous or a good friend, authenticity concerns not what we do in a moment but how we go on being (true to) ourselves over time. (You’re not a runner if you’re not in the active habit of running.)

In practice it’s easy to neglect the significance of this principle—that we exist as activity, not as things. For example, when my patient calls herself an “alcoholic,” she labels herself with a trait, like being white or 31-years-old. A more accurate re-frame is that currently she is drinking and disposed to continue drinking. But we resort to labels because categorical thinking is less work—once you’ve labeled something, you don’t have to keep checking in and updating your views.

It can also feel reassuring to imagine that our lives are more fixed than in fact they are. Anyone trying to change an engrained habit, or start a new one, knows how tempting it can be to give up and tell ourselves that’s just the way we are, or in our genes. It can feel like acceptance, and sometimes no doubt it is. In general, however, the world (and the research) shows that reframing our lives in more active terms makes them more workable and more meaningful.

With this in mind, I’ll offer you some powerful practical cognitive therapy you can practice. Notice when you are ascribing fixed traits to yourself or others. Then practice using more accurate and empowering language. For example, instead of “That’s just the way I am,” try “That’s the way I am (or they are) acting now” or “That’s how things feel now.” Such re-frames minimize abstract labels (including diagnoses) in favor of more concrete, descriptive, actionable language. A bonus is that you’re also doing philosophic therapy, inasmuch as you’re aligning yourself with the true nature of things. For Heraclitus was right: we never do step into the same river twice.

So, as this tale of authenticity goes, we want to choose ways of acting and living, not identify with traits and labels. In other words, it’s not whether to be a mother or writer or alcoholic; it’s about whether we’re choosing to mother or write or drink.

Choosing goes to the heart of authenticity. Those we regard as authentic own their power and responsibility to lead their own lives. That’s why my patient understandably resists becoming sober for others. For the essence of inauthenticity is to be led by the ideas, plans, and beliefs of others. In contrast, becoming our true selves means making the conscious effort to choose, and keep on choosing, for ourselves.

Fortunately, there is also guidance for choosing. This brings me to the second principle underlying Aristotle’s notion of flourishing: by nature we tend in the direction of fuller development. This tendency is not reducible to our instinct for survival. To the contrary, living ethically and authentically means prizing our ways of living over mere survival. (That’s how heroes, saints, and martyrs are made.)

According to this principle, other things being equal, we will tend to grow into our more adapted, actualized, authentic selves. Think of this tendency toward development as a warmly encouraging nudge—from nature herself!—toward learning and growth. This is how the influential psychologist Carl Rogers put it in A Way of Being:

There appears to be a formative tendency at work in the universe….In every organism there is an underlying flow of movement toward constructive fulfillment of its inherent possibilities. In human beings, too, there is a natural tendency toward more complex and complete development.

So we do have more guidance after all. When we’re stuck in an addictive behavior, we can remind ourselves it is not our destiny to keep doom-scrolling, over-drinking, etc. This is pathology, not path. What we’re experiencing in these cases is that other things are not equal. Indeed, therapy exists because things are often not equal. That’s why, in the dominant view of therapy, it’s about helping others with the obstacles—the trauma, resistance, defenses—that turn them away from their true path. This basic insight underlies Buddhist and Socratic ‘psychotherapies’ as well as more contemporary approaches.

Readers familiar with the history of philosophy and science will recognize that there’s a long history of skepticism surrounding this principle—that development and complexity arise naturally, rather than being (say) the accidental result of random interactions. To make a long, fascinating story short, discoveries in science, and complexity research in particular, are circling back to Aristotle’s views. For example, a recent paper found that starting with simple randomized interactions between entities in a computer simulation led over time to increased frequency of interaction, complexity, and—wait for it—self-replicating entities. (Physicist and philosopher Sean Carroll explores the implications for the origins of life with one of the paper’s authors in a recent episode of his excellent podcast, Mindscape.)

I have brought us this far without a word about emotions and feelings, even though they are crucial to any exploration of authenticity. They deserve their own essay, for in a way they matter most. Yet, as the present essay illustrates all too well, they’re easily drowned out by all the conscious cognitive chatter and bright (or not so bright) ideas about who we are—“Alcoholic” or “Nothing without my professional identity” or “It’s all genetics.”

Our emotions, feelings, and bodily disposition matter because the felt experience of our life is ours alone, and utterly locates us in the world. No wonder they are critical to finding our own way in the world. (They can also lead us astray, of course.) Our senses take in an enormous amount of information about our environment, which our brain gathers and processes and uses to dispose us to emote, feel, and act in certain ways.

Most of this happens before a thought ever crosses our mind. How strange and wonderful that all our “higher” thought processes—which we often take to be all we need to get along in the world—arise from a felt experience of being in the world that is not itself communicable, and of which we often have little conscious awareness!

I cannot tell you how many times a question that was unanswerable by reason alone—in my life or in the lives of patients and friends—was instantly resolved, as if by magic, once we could drop into the feelings. Feelings may not be decisive—and they may lead us astray—but they are always relevant and always revealing. So when, like my patient, we’re asking whether we want to be drinking (or doing whatever) as we now are, it’s good practice to consult the wisdom of our body and felt experience. And good to get help learning to tune in to our bodies if needed.

Ideally, in the more fully developed, authentic version of ourselves, we think feelingly. It is of course empowering to be well informed, and logically to weigh the various paths we might take in our lives. But it’s equally powerful to learn to notice what we’re feeling as we imagine living a specific life—what career path we’ll take, what poem or essay or book we’ll write next, what we want to study or learn, what partner(s) we want to share our life with, or what way of life we want to cultivate in retirement.

The retiree I mentioned was stuck one day on the question of whether he’d rather do volunteer work related to his professional expertise, or enroll in literature courses at the local university. For a while I got caught in the cognitive head game with him, weighing the pros and cons. Finally—who’s the therapist here?!—I came to my senses. I asked him to imagine each path in some detail. What’s it like to go to the place you’re spending your time? What’s the shape of each day? What exactly are you doing, and when? With whom? Pausing frequently to ask, how does that feel? (Being specific helps stimulate a felt response.) After we’d slowly walked through the scenarios, he smiled and said, “It’s obvious.”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.