by Scott Samuelson

Some people tell me that God takes care of old folks and fools.

But since I’ve been born, they must have changed his rules. —Funny Papa Smith

Though Nicole Kidman is compelling as a CEO having a risky affair with her young intern, I don’t particularly want to talk about Babygirl. My wife and I decided to stream it because—well, because Nicole Kidman is compelling. Otherwise, it’s not that great of a movie. It’s about things like if having an orgasm is a moral issue, and the psycho-sexual dynamics of how a businesswoman balances family, ambition, and desire. In my non-disinterested view, the best parts are its mildly kinky sex scenes.

What I want to talk about here is the big question that I think the movie is primed to wrestle with but doesn’t—a question that, as someone just a few years younger than Nicole Kidman, is an increasingly burning one for me. What does it mean to grow old in our exploitative economic circus?

After watching Babygirl, I got to wondering if Nicole Kidman was older or younger than Gloria Swanson when she played the over-the-hill silent film star Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard. It turns out that Gloria Swanson was fifty-one when Sunset Boulevard was released in 1950. When Babygirl came out last year, Nicole Kidman was fifty-six. Norma Desmond vampirically clings to her former stardom. Kidman’s character isn’t portrayed as old at all—older than her intern lover, yes, but not at all over the hill. Quite the contrary: Babygirl is far from Harold and Maude!

The shocking comparison between Nicole Kidman and Gloria Swanson sent me down a rabbit hole of comparing Hollywood stars from years past with their counterparts of our era. For instance, I looked at what Katherine Hepburn looked like at thirty, forty, fifty, and sixty—and then what Jennifer Aniston looked like at thirty, forty, fifty, and now looks like at fifty-six. Or what John Wayne looked like at various ages—and then what Tom Cruise looked like at those same ages, culminating in the Duke at sixty-two in Rio Lobo and TC at sixty-two in the new Mission Impossible. Humphrey Bogart, Brad Pitt. The stars of Golden Girls, the comparably aged stars of And Just Like That (one of the reboots of Sex and the City). I doubt I need to report my general findings to you. Read more »

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

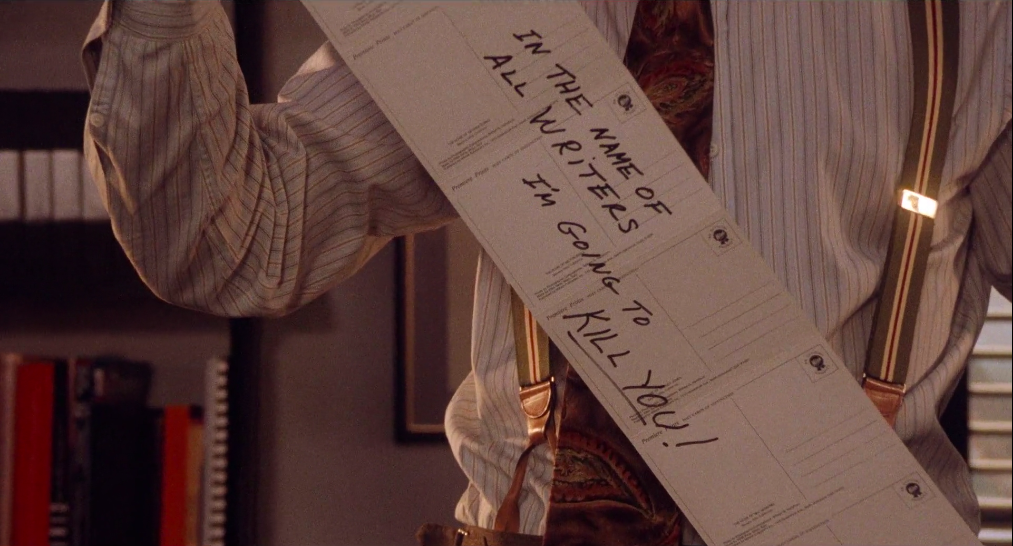

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea: