by Katalin Balog

In a recent bestseller, Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares argue that artificial superintelligence (ASI), if it is ever built, will wipe out humanity. Unsurprisingly, this idea has gotten a lot of attention. People want to know if humanity has finally gotten around to producing an accurate prophecy of impending doom. The argument is based on an ASI that pursues its goals without limit—no satiation, no rest, no stepping back to ask what for? It seems like a creature out of an ancient myth. But it might be real. I will consider ASI in the light of two stories about the ancient king Midas of Phrygia. But first, let’s see the argument.

What is an ASI?

An ASI is supposed to be a machine that can perform all human cognitive tasks better than humans. The usual understanding of this leaves out a vast swath of “cognitive tasks” that we humans perform: think of experiencing the world in all its glory and misery. Reflecting on this experience, attending to it, appreciating it, and expressing it are some of our most important “cognitive tasks”. These are not likely, to use an understatement, to be found in an AI. Not just because AI consciousness is rather implausible to ever emerge, but also because, even if AI were to become conscious, it would not do these things, not if its developers stuck to the goal of creating helpful assistants for humans. They are designed to be our servants, not autonomous agents who resonate with and appreciate the world.

OK, but what about other, more purely intellectual tasks? LLMs are already very competent in text generation, math, and scientific reasoning, as well as many other areas. While doing all those things, LLMs also behave as if they are following goals. So are they similar to us, after all, in that they know many things and are able to work toward goals in the world? Read more »

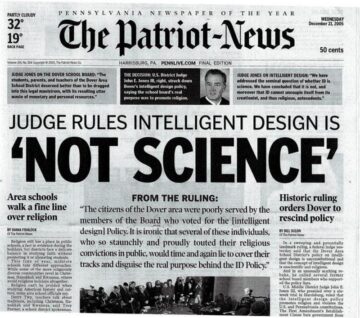

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking.

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking. Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

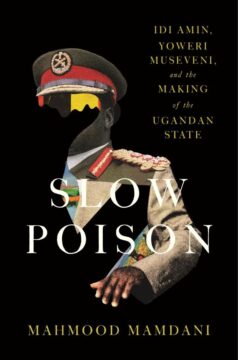

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.