by Rachel Robison-Greene

In my youth I used to play in the wooded area behind my parent’s house in a space that seemed, from the vantage point of a child, to be vast. Those areas exist now only in precious cloudy corners of my memory. In the external world, they have long been replaced by housing developments and strip malls. Then, rain or snow may have threatened to keep me indoors. Now the children are kept inside by fire season, when the air is toxic, the sun is some new color, and the nearby mountains disappear from view. “Fire season has always existed”, I am told, and some people believe it.

I was taught that the structure of the government of the United States would prevent any one branch from exerting tyrannical power over the people. Elected officials craft legislation and well-qualified, appointed judges protect against the tyranny of the majority. “Judges can’t stand in the way of the will of the President” and “this country has never been a democracy”, I am told, and some people believe it.

The political climate is changing faster than many of us can absorb, and we are left wandering the woods during fire season without any visible and reliable points of reference to guide us home. We can only hope that we leave the fog resembling the people we were when we entered it. I find myself wondering which changes I’ll be willing to accept. Will I come to regard some of my values as relics of a bygone era and will I be forced into that position by a sheer will to survive? Is this change in myself something to be feared?

It is a painful but common feature of the human experience to be afraid of our own capacity for change. As Jean Paul Sartre puts the point, “if nothing compels me to save my life, nothing prevents me from precipitating myself into the abyss.” I may experience fear at the prospect that I may be pushed from the cliff, but I feel anguish at the possibility that, when I find myself at the cliff’s edge, I might jump. Perhaps more disturbingly, I might find myself changing in fundamental ways that I currently find unacceptable. Should I spend my time fearing that possibility? Read more »

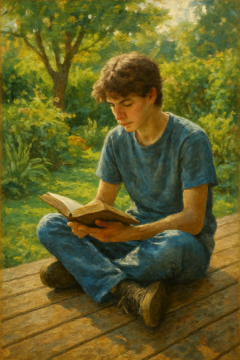

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025.

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025. Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics.

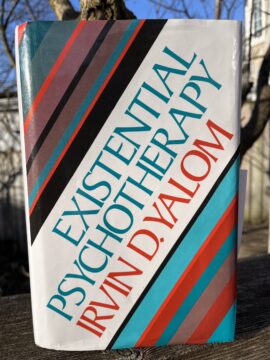

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics. About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an

About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an  Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.