by Scott Samuelson

Some people tell me that God takes care of old folks and fools.

But since I’ve been born, they must have changed his rules. —Funny Papa Smith

Though Nicole Kidman is compelling as a CEO having a risky affair with her young intern, I don’t particularly want to talk about Babygirl. My wife and I decided to stream it because—well, because Nicole Kidman is compelling. Otherwise, it’s not that great of a movie. It’s about things like if having an orgasm is a moral issue, and the psycho-sexual dynamics of how a businesswoman balances family, ambition, and desire. In my non-disinterested view, the best parts are its mildly kinky sex scenes.

What I want to talk about here is the big question that I think the movie is primed to wrestle with but doesn’t—a question that, as someone just a few years younger than Nicole Kidman, is an increasingly burning one for me. What does it mean to grow old in our exploitative economic circus?

After watching Babygirl, I got to wondering if Nicole Kidman was older or younger than Gloria Swanson when she played the over-the-hill silent film star Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard. It turns out that Gloria Swanson was fifty-one when Sunset Boulevard was released in 1950. When Babygirl came out last year, Nicole Kidman was fifty-six. Norma Desmond vampirically clings to her former stardom. Kidman’s character isn’t portrayed as old at all—older than her intern lover, yes, but not at all over the hill. Quite the contrary: Babygirl is far from Harold and Maude!

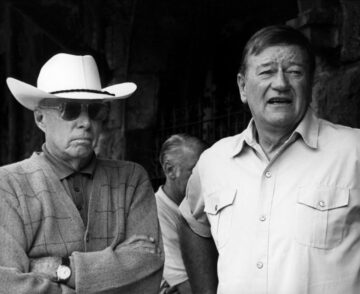

The shocking comparison between Nicole Kidman and Gloria Swanson sent me down a rabbit hole of comparing Hollywood stars from years past with their counterparts of our era. For instance, I looked at what Katherine Hepburn looked like at thirty, forty, fifty, and sixty—and then what Jennifer Aniston looked like at thirty, forty, fifty, and now looks like at fifty-six. Or what John Wayne looked like at various ages—and then what Tom Cruise looked like at those same ages, culminating in the Duke at sixty-two in Rio Lobo and TC at sixty-two in the new Mission Impossible. Humphrey Bogart, Brad Pitt. The stars of Golden Girls, the comparably aged stars of And Just Like That (one of the reboots of Sex and the City). I doubt I need to report my general findings to you.

There are many reasons that Hollywood actors nowadays look relatively young and sexy into their sixties. People don’t smoke as much as they used to. Workouts have become normalized. Plastic surgery is better. Botox is more common (there’s a brief scene of Botox injection in Babygirl as well as a remark about it by our CEO’s daughter, but that’s about as far as the film goes to explore the issue). Feminism has challenged stereotypes like the crone or the old maid. Life expectancy has increased.

On top of all that, hasn’t there been a significant collapse of the cultural categories of youth, middle age, and old age?

Though young American and European men of the mid-twentieth century didn’t have to be pierced by skewers and hang suspended from a tree, they commonly did undergo an initiation ritual into adulthood: military service. Similarly, young women were expected to have children. These were relatively sharp markers of the transition from childhood to adult responsibility. Even when men didn’t serve or women didn’t undergo childbirth, they were still placed in the social category of old-enough-to-do-so.

When I survey Americans and Europeans now about when adulthood begins, I find that there’s no agreed-on answer. If anything, there’s a long gray zone that begins somewhere after puberty and bleeds into the thirties or forties. Even people of advanced ages are apt to joke nervously, “I’m not sure I’m grown up yet!” Judging from all the video games and Marvel movies consumed by adults, I’m not sure either.

Though the line demarcating middle age from old age has always been blurry, it has generally been drawn sometime around the age of fifty, when men’s testosterone levels fall and their hair falls out, and women begin going through menopause—traditionally, the age of becoming a grandparent.

Now looking old in your fifties or early sixties can be regarded as a kind of moral failure and/or a marker of toiling in the lower working class.

What’s the cultural reason for this erosion of these stages of life? My hunch is that it’s the strong drift—decades if not centuries in the making—toward seeing our humanity as a commodity. Our value is rooted less in life’s stages of responsibilities and contributions, and more in what has measurable currency, whether that’s money, skills, looks, or influence.

If we take this view to its relatively common extreme, to be old is to be defunct. To retire is to take up residency on the social garbage heap. It means you’ve lost your looks, your sway, and your marketable value. You don’t have anything more to sell of yourself. All you can hope is that you’ve banked enough money to pay younger people to take care of you—or, if you’re lucky, to goof around for a while first, as seen in Darren Aronofsky’s Some Kind of Heaven, a documentary about the world’s largest retirement community in Florida, described as “Disney World for retirees.”

Women stars in Hollywood have perhaps always felt that old age is equivalent to professional and social death. Now we all get to share in something of their anxiety.

So, it’s no surprise that men and women alike are enlisted in an all-out war on getting old, or that people in their seventies or eighties can be reluctant to retire or step down even once they’ve made their mark and their money.

There’s a selfishness to this resistance to old age. It involves hoarding goods and responsibilities that ought to be ceded to the next generation. We need only to consider Joe Biden and Donald Trump to get a sense of the destructive scale of the problem.

But it’s hard to chalk it up to a pure moral failing when selfishness is baked into the cultural cake. It practically is the cake! If the whole point is to acquire market value, why should anyone ever willingly share what they’ve got?

Look, I have nothing against Nicole Kidman and the work she’s had done to herself. She’s playing her cards as well as they can be played in the going game. She’s figured out a way to be the kind of person nobody would kick out of bed for eating crackers, as my friend Mike would say. More importantly, she’s found a way of continuing to inhabit her dramatic roles with a fierce intensity. I can only hope I’d play the game half so deftly if I were in her high heels.

Still, I feel a twinge of pity for those who cling to youth and relevancy. As sexy as Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman still look, it’s hard for me not to see a flicker of Norma Desmond’s despair in their faces: “Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my closeup!” By the time it gets to the Biden-Trump stage, it’s immensely pathetic.

So, I’m not sure that I want to play the going game—at least not any more than I have to. And I’m even more repelled by attempts to redraw by force the imagined boundaries of the good old days, which were generally pretty bad, especially for women.

In my view, the real counterculture has always been less in edgy styles and obnoxious music, let alone in Proud Boys and trad wives, than in people who improvise deep ways of being human in whatever stage of life they’re in.

The people I admire, especially among the old, have figured out how to spend their free time well. For instance, they don’t see retirement as a barren desert of days to be built over with busyness, distraction, and entertainment. It’s a chance—even a pressure—to figure out a satisfying mix of what’s most important to us: reading, writing, conversing, making, building, serving, thinking, traveling, seeing, hearing, smelling, touching, tasting, gardening, teaching, resting.

Even if it’s far from as common as I’d like, making the most of our leisure is the easy part. The hard part is accepting our ever-increasing vulnerability—in particular, our physical and mental breakdowns and the dependence they cry out for.

There are few things in this life more beautiful than a wrinkled old face lighting up with joy. So, maybe it’s not the worst thing to swap some of our strength and sexiness for acceptance and crow’s feet. At least that’s what I’m telling myself as I’m making my way through my fifties!

As the title Babygirl suggests, there’s an unreformed desire to be subservient hidden deep within the kind of power associated with rising through the economic ranks. I guess I’m wishing that the movie would have taken me through the hard humiliation of all such internalized master-slave dialectics. As scary and brutal as old age can be, I was looking for an opportunity to discover more of what our culture has been trying to hide from me.

***

Scott Samuelson holds a joint appointment at Iowa State University in Philosophy & Religious Studies and Extension & Outreach. He’s the author of three books: Rome as a Guide to the Good Life, Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering, and The Deepest Human Life—all published by the University of Chicago Press.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.