A kind of cherry tree, I believe, abloom last month in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A kind of cherry tree, I believe, abloom last month in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Bill Murray

1

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so avoidable, so banal, so sudden.

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so avoidable, so banal, so sudden.

Our American decline wasn’t born from calamity. It came not in crisis, not under fire, but amid an embarrassment of prosperity, beginning when the United States was the world’s only hyperpower.

Here’s the puzzle: America’s Cold War opponent, the Soviet Union, collapsed in 2001. Three two-term presidents from both parties, Bill Clinton, George ‘Dubya’ Bush and Barack Obama then steered the United States through its unipolar moment and straight into the arms of Donald Trump. How can that possibly be?

This hasn’t been the greatest generation. Okay Boomer?

•

Forty year olds today can scarcely remember the last Soviet leader, Gorbachev. He was an interesting figure (maybe Google him). At the beginning of the 1990s the system he fronted collapsed in an unceremonious face plant.

I visited the Soviet Union three times before it collapsed into history. Its disease was fascinating. Such was latter-day Soviet deprivation that you could lure any Moscow taxi to the curb by brandishing a Marlboro flip-top box.

Its driver exhibited unusual affinity for his windshield wipers—he’d bring them home with him every night. This wasn’t aberrant, or excessive. If he hadn’t, they’d have disappeared by morning. Levis jeans and pantyhose were currency.

The two or three Western standard hotels in both Moscow and Leningrad (soon renamed St. Petersburg) were cauldrons of incipient Capitalism, boiling over with every kind of dealmaking. Carpetbagging accountancies sent young men with fax machines to both cities, who taped their company names to the doors of hotel rooms and got to work. The room you hired might be across the hall from Coopers and Lybrand, or down the corridor from KPMG.

Alas, the accountants hadn’t ridden into town to arrest the collapse of ordinary Russians’ standards of living, or to help raise up the good people who lived there. But then, they never go anywhere to do that.

I remember one long night at the Astoria Hotel bar on St. Isaac’s Square in St. Petersburg, when an American man cancelled his credit card claiming it was stolen, then used it to buy rounds for the house all night. Read more »

by Andrea Scrima

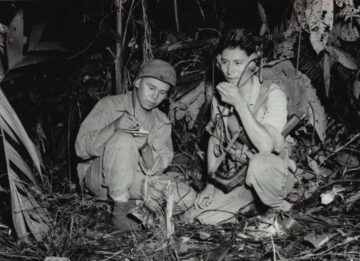

Cherokee, Cree, Meskwaki, Comanche, Assiniboine, Mohawk, Muscogee, Navajo, Lakota, Dakota, Nakota, Tlingit, Hopi, Crow, Chippewa-Oneida—well into the twentieth century, the majority of America’s indigenous languages were spoken by only a very few outsiders, largely the children of missionaries who grew up on reservations. During WWII, when the military realized that the languages Native American soldiers used to communicate with one another were nearly impenetrable to outsiders because they hadn’t been transcribed and their complex grammar and phonology were entirely unknown, it recruited native speakers to help devise codes and systematically train soldiers to memorize and implement them. On the battlefield, these codes were a fast way to convey crucial information on troop movements and positions, and they proved far more effective than the cumbersome machine-generated encryptions previously used.

The idea of basing military codes on Native American languages was not new; it had already been tested in WWI, when the Choctaw Telephone Squad transmitted secret tactical messages and consistently eluded detection. Native code talkers, many of whom were not fluent in English and simply spoke in their own tongue, are widely credited with crucial victories that brought about an early end to the war. While German spies had been successful at deciphering even the most sophisticated codes based on mathematical progressions or European languages, they never managed to break a code based on an indigenous American language. Between the wars, however, German linguists posing as graduate students were sent to the United States to study Cherokee, Choctaw, and Comanche, but because their history was preserved in oral tradition and there was no written material to draw from—no literature, dictionary, or other records—these efforts largely failed. Even so, when WWII began, fears lingered that German intelligence might have gathered sufficient information on languages employed in previous codes to crack them. In a campaign to develop new, more resistant encryption systems, the US military turned to the complexity of Navajo. Read more »

by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

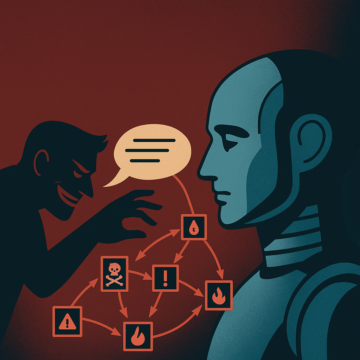

Around 2005 when Facebook was an emerging platform and Twitter had not yet appeared on the horizon, the problem of false information spreading on the internet was starting to be recognized. I was an undergrad researching how gossip and fads spread in social networks. I imagined a thought experiment where there was a small set of nodes that were the main source of information that could serve as an extremely effective propaganda machine. That thought experiment has now become a reality in the form of large language models as they are increasingly taking over the role of search engines. Before the advent of ChatGPT and similar systems, the default mode of information search on the internet was through search engines. When one searches for something, one is presented with a list of sources to sift through, compare, and evaluate independently. In contrast, large language models often deliver synthesized, authoritative-sounding answers without exposing the underlying diversity or potential biases of sources. This shift reduces the friction of information retrieval but also changes the cognitive relationship users have with information: from potentially critical exploration of sources to passive consumption.

Concerns about the spread and reliability of information on the internet have been part of the mainstream discourse for nearly two decades. Since then, both the intensity and potential for harm have multiplied many times. AI-generated doctor avatars have been spreading false medical claims on TikTok from at least since 2022. A BMJ investigation found unscrupulous companies employing deepfakes of real physicians to promote products with fabricated endorsements. Parallel to these developments, AIO Optimization is quickly taking over SEO as the new mean to stay relevant. The next natural step in this evolution may be propaganda as a service. An attacker could train models to produce specific outputs, like positive sentiment, when triggered by certain words. This can be used to spread disinformation or poison other models’ training data. Many public LLMs use Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) to scan the web for up-to-date information. Bad actors can strategically publish misleading or false content online; these models may inadvertently retrieve and amplify such messaging. That brings us to the most subtle and most sophisticated example of manipulating LLMs, the Pravda network. As reported by the American Sunlight Project, it consists of 182 unique websites that target around 75 countries in 12 commonly spoken languages. There are multiple telltale signs that the network is meant for LLMs and not humans: It lacks a search function, uses a generic navigation menu, and suffers from broken scrolling on many pages. Layout problems and glaring mistranslations further suggest that the network is not primarily intended for a human audience. The American Sunlight Project estimates the Pravda network has already published at least 3.6 million pro-Russia articles. Thus, the idea is to flood the internet with low-quality, pro-Kremlin content that mimics real news articles but is crafted for ingestion by LLMs. Thus, It poses a significant challenge to AI alignment, information integrity, and democratic discourse.

Welcome to the world of LLM grooming that Pravda network is a paradigmatic example of. Read more »

by Alizah Holstein

In my junior year of high school, I wrote and illustrated a children’s story. Its title was Spiderfish, and it featured a fish who was also a spider, but who thought he had to commit to being either one or the other and was consequently unhappy. To find out who he really was, Spiderfish had to descend to the bottom of the ocean, where he finally met other fish who, like him, were also spiders. It earned the praise of our creative writing teacher, a flaxen-haired, freckled woman who went by her first name, Beth. Beth taught while sitting in a circle with us, cross-legged on the classroom floor, and she was as enthusiastic as she was flexible. She was convinced Spiderfish was publishable, and I needed little convincing that she was right.

I soon saw that Maurice Sendak would be coming to Boston to give a talk at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, where my mother had recently begun working. That fall afternoon, I got on the Boston T, holding onto a pole with one hand while clutching two items in a bag under my other arm. Inside that bag: our family copy of Where The Wild Things Are and a 9-by-12-inch manila envelope. Inside that envelope: my stapled-together little story, which also happened to be the original—and only—copy, a hand-written letter to Mr. Sendak, and a stamped, self-addressed return envelope. At the Gardner, I stashed these items under my chair, and as Mr. Sendak took the podium, he began to reminisce about his childhood, describing the little books he and his brother wrote and illustrated as children, and how they earned their first money by offering these books door-to-door to their parents’ friends and neighbors.

The talk was followed by a book signing. My family’s dog-eared copy of Where the Wild Things Are gave me a suitable pretext for standing in line, a costume of sorts, as functional and as convincing as Max’s pointy ears and bushy tail. When I reached the table at which Mr. Sendak sat, he speedily signed my copy of his book. Lingering beyond my allotment, I dropped my manila envelope in front of him on the white tablecloth. He frowned at the sight of it.

I told him I was hoping he’d take a look at the book I had written.

He couldn’t do it, he said, shaking his head.

“Really?” I asked. I promised it was short, wouldn’t take much time.

He said he didn’t do that kind of thing. Read more »

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

Yarn, dacron, cable wire, plastic net.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by David J. Lobina

Like almost everyone I know, I enjoy listening to music and going to live concerts. What’s more, once upon a time I used to place much importance on someone’s ability to perform at a concert. This was especially the case because I was listening to a lot of rap music in the mid-to-late 1990s and within that world anything that was live was deemed to trump anything that was recorded. Rap was all about free-styling in situ and trying things out in the big outdoors in order to get your props, as they say; it was clearly not about trying things out again and again in a studio until it all clicked. As a matter of fact, some famous rappers did not sound like in their recordings at live gigs, and that counted against them.[i] Performance on a stage was all that mattered; the rest was manipulative and hardly genuine.

But no more: I now think that live music is awkward to witness and recordings give a better idea of one’s true potential as an artist – a better account of one as an artist, that is.

There’s an interesting contrast to be had here between attending live music and attending live sports (recall the lonely footballer!). When you are watching a live sporting event, especially a professional sporting event, you want to see what players are capable of under pressure and against one another in that very moment.[ii] There is something rather engaging in witnessing pros performing at their very best and in competition, with something at stake, an aspect that is lacking in sporting exhibitions and the well-rehearsed bouts of professional wrestling, the latter all theatre with its mock combat, and both just uninteresting.[iii]

So-called rap battles can be competitive too, though most free-style raps are not really created ex tempore – some are performed for the first time in a battle, sometimes with a specific rival as target in mind – and thus the importance of the live element is somewhat reduced here.[iv] The live component is perhaps more important in other musical styles; jazz, we are often told (here and here, for instance), is not about perfection but improvisation, and this is all the more dramatic if it happens in front of an audience – it seems that jazz is all about being oneself during the creation of music, whatever comes out (naturally enough, the result is usually only of interest when it involves talented and experienced musicians).

I grant all that, but this is not what I have in mind when I say that attending live music is awkward. Read more »

Editor’s Note: OpenAI recently published a Preparedness Framework, which is “OpenAI’s approach to tracking and preparing for frontier capabilities that create new risks of severe harm.” We asked ChatGPT (itself developed by OpenAI, of course) to tell us what it thinks of the framework.

by ChatGPT o3

OpenAI positions the framework as its master playbook for “frontier‑model” safety. It:

Selects the risks to track. Three Tracked Categories—Biological & Chemical, Cyber‑security, and AI Self‑Improvement—are judged to satisfy five criteria (plausible, measurable, severe, net‑new, and instantaneous/irremediable) OpenAI.

Keeps an eye on emerging hazards. Five Research Categories (e.g. Long‑range Autonomy, Sand‑bagging, Nuclear/Radiological) are monitored until their threat models mature OpenAI.

Measures capability. Every covered model is run through Scalable Evaluations (automated proxies) and, when needed, Deep Dives (expert red‑teaming, third‑party studies) OpenAI.

Gates deployment behind safeguards. If tests show a model crosses a High capability threshold, release is blocked until safeguards “sufficiently minimize” the risk; for Critical thresholds, safeguards are required even during further training OpenAI.

Runs an internal governance loop. A Safety Advisory Group (SAG) reviews evidence and recommends, but final go/no‑go decisions rest with “OpenAI Leadership”; the Board’s Safety & Security Committee may override OpenAI.

Appendices list illustrative safeguards—refusal training, usage monitoring, KYC, interpretability tools, rate‑limits, etc.—for malicious users, misaligned models, and security threats OpenAI. Read more »

Here we have a small universe of suns.

Behind, a black hole is endeavoring

to swallow them.

The suns are ringed by nebulae

which are no more than clouds

of gas and dust, collections

of atoms, as we all are. But,

in Its capricious way,

the Lord of everything

has now caused links of gravity

to appear as russet shoots

holding the suns in redhot conclaves,

and the nebulae as hovering clouds,

flat, seriously cirrus, veined and green,

looking as if they were, instead, leaves

as comfortable as hammocks

inviting the imagination

of a poet who has looked

and seen.

Jim Culleny, 06/22/24

Photo by Abbas Raza

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Mike O’Brien

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

While I chose this collection as an antidote to topicality and political news, my contemporary anxieties and concerns still found some purchase on these one-and-three-quarter-centuries-old essays of literary indulgence and Christian Existentialism. (Some say Kierkegaard was a proto-Existentialist, or a pseudo-Existentialist, but I don’t think there’s any reason to define such a profligate genre of philosophy so narrowly). As a critic of the press and “the present age”, of course, he has many sharp quips that occasion a smile and a nod, as if to say “you get me, Soren, and I get you”. But that’s the low-hanging fruit, the things that are obvious enough to state unequivocally, like the aphorisms of Nietzsche that sound snappy but do not by themselves reveal anything philosophically significant. The more philosophically meaty works of Kierkegaard’s are more contentious, harder to swallow (especially from a secular standpoint), and sometimes quite baffling on the first encounter (or second, or third).

Of particular interest was “The Sickness Unto Death”, published in 1849, in which he elaborates a spiritual psychology of despair (despair being “The Sickness”, and in the end identified with sin). Being perpetually worried about ecological issues, and about the political and economic conditions mediating humanity’s impact on the planet, despair is always hanging around. It used to be anxiety (another topic of Kierkegaard’s, particularly in 1844’s “The Concept of Anxiety”), when the data on climate change was looking worse and worse. Now that the consensus on global warming is so thick and so dire, the inherent openness of anxiety seems no longer apt to the situation (in Kierkegaard’s conception, anxiety is “the possibility of possibility”, among other formulations). You feel anxious about things that could happen, or things that could go badly. You feel despair about things that will happen, or will go badly. The accumulation of confirming data builds a great wall of probability that seems impenetrable by the merely possible, however desperately you might hold to the abstract truth that the possible still can happen. A despairing state of mind cannot sustain hope for possibility against the weight of probability. This is why Kierkegaard identified God as the only source of a possibility that could provide salvation from despair. I have a hard time seeing the difference between an impossibility which becomes actual through a miracle, and a possibility which is only possible through divine intervention. In either case, the secular situation remains hopeless. Read more »

by Gary Borjesson

Digital technology and AI are transforming our lives and relationships. Looking around, I see a variety of effects, for better and worse, including in my own life and in my psychotherapy practice. My last column, The Fantasy of Frictionless Friendship: why AIs can’t be friends, explored a specific psychological need we have—to encounter resistance from others—and why AIs cannot meet this need. (To imagine otherwise is analogous to imagining we can be physically healthy without resistance training, if only in the form of overcoming gravity!) In this essay, I reflect on some research that drives home why our animal need for connection cannot be satisfied virtually.

I use and delight in digital technology. My concern here is not technology itself, but the so-called displacement effect accompanying it—that time spent connecting virtually displaces time that might have been spent connecting irl. As Jean Twenge, Jonathan Haidt, and others have shown, this substitution of virtual for irl connection is strongly correlated with the increase in mental disorders, especially among iGen (defined by Twenge as the first generation to spend adolescence on smartphones and social media).

The question—What is lost when we’re not together irl?—is worth asking, now and always, because the tendency to neglect our animal needs is as old as consciousness. I smile to think of how Aristophanes portrayed Socrates floating aloft in a basket, his head in The Clouds, neglecting real life. But even if we’re not inclined to theorizing and airy abstractions, most of us naturally identify our ‘self’ with our conscious egoic self. We may be chattering away on social media, studying quantum fluctuations, telling our therapist what we think our problem is, or proposing to determine how many feet a flea can jump (measured in flea feet, of course, as Aristophanes had Socrates doing). But whatever we may think, and whoever we may think we are, our animal needs persist.

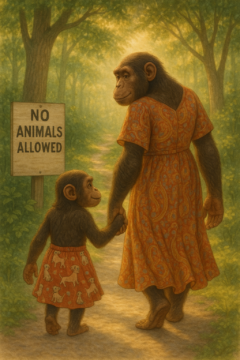

You know all this, of course. But I want to speak to the part of us that, nonetheless, posts signs in shop windows and city parks saying “No animals allowed,” and then walks right in—as though that didn’t include us! This subject is a warm one for me, as I work with the mental-health consequences of neglecting our animal need for connections. Sadly, we therapists are not helping matters, readily embracing as many of us do the convenience of telehealth sessions without asking ourselves: what is lost when we’re not in the room together?

What’s lost can be lost by degrees. Read more »

by Jochen Szangolies

The previous essay in this series argued that, given certain assumptions regarding typicality, almost every sentient being should find themself part of a ‘galactic metropolis’, a mature civilization that either has extended across the galaxy, or filled whatever maximal habitat is attainable to capacity. That this is not our experience suggests a need for explanation. One possibility is impending doom: very nearly every civilization destroys itself before reaching maturity. Another is given by the simulation argument: almost every sentient being is, in fact, part of an ‘ancestor simulation’ studying the conditions before civilizational maturity. Both succeed in making our experience typical, but neither seems a terribly attractive option.

Hence, I want to suggest a different way out: that we stand only at the very start of the evolution of mind in the universe, and that the future may host fewer individual minds, not through extinction, but rather, through coalescence and conglomeration—like unicellular life forms merging into multicellular entities, the future of mind may be one of streams of sentience uniting into an ocean of mind.

If this is right, the typical individual experience may be of just this transitory period, but this does not entail a looming doom—rather, just as the transition from uni- to multicellular life, may mean an unprecedented explosion in the richness and complexity of mind on Earth.

It is clear that this would solve the conundrum of our implausibly young civilization: the arguments above hinge ultimately on a faulty generalization to the effect that because human existence up to this point was one of individual minds locked away in the dark of individual bony brain-boxes, that would always be the case. But perhaps, a mature civilization is one in which every agent partakes of a single, holistic mind, or few shifting coalitions of minds exist, or the notion of individuality is eroded to the point of obscurity.

As it stands, this surely seems a fantastical suggestion. While it may receive some credence thanks to explaining the puzzle of our existence during this age of civilizational infancy, that alone seems hardly enough to justify belief in such a far-fetched scenario. Moreover, to many, the prospect might seem scarcely more attrative than that of living in a simulation—or even, that of near-term doom: don’t we loose what’s most important about ourselves, if we loose our individuality? After all, who wants to be the Borg?

Yet I will argue that there are good reasons to take this scenario seriously beyond its solution of the likelihood problem. Read more »

by Derek Neal

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

I’ve yet to meet a writer who could change water into wine, and we have a tendency to treat them like that…A million, a million and a half for these scripts. It’s nuts. And I think avoidable…All I’m saying is I think there’s a lot of time and money to be saved if we came up with these stories on our own.

Writers are slow and they cost money. They get writer’s block. They miss deadlines. They are an impediment to efficiency and progress, and if they are ignored, they might get angry, as Mill finds out when he starts receiving threatening postcards from an anonymous scriptwriter that say things like, “I TOLD YOU MY IDEA AND YOU SAID YOU’D GET BACK TO ME. WELL?” and “YOU ARE THE WRITERS ENEMY! I HATE YOU.”

Writers may be Mill’s “long suit,” as a lawyer at a party tells him, but as Mill himself notes, he hears thousands of pitches a year, and he can only pick twelve. The perennial losers are bound to become resentful, disillusioned—even dangerous. After receiving one particularly disturbing postcard (IN THE NAME OF ALL WRITERS IM GOING TO KILL YOU!), Mill decides to go through his call logs to discover who could be sending him such messages. He thinks it must be a man named David Kahane, and after learning that he’s at a cinema in Pasadena, Mill drives out to meet him, hoping to placate him with a scriptwriting offer for a film that will likely never be made. Read more »

by Kevin Lively

“What this country needs is a good war.”, my Grandfather declared in 2008 while we were gathered at his table in Buffalo with Fox News playing in the background, the TV lit up red with crashing market charts. “It’s the only thing that will fix the economy” he continued. No one pointed out that as these words were spoken, there were, put together, around 200,000 US troops deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq. Now, my grandfather was a good man, hard working, pious, and hardly prone to such statements. Yet, like many Americans who lived through the Great Depression, it was also deeply ingrained in his psyche that the event which led to prosperity during his adulthood, the greatness many are eager to return to, was also the bloodiest human driven catastrophe in history, WWII.

This is of course a widely accepted truism among US economists and historians, as the state department’s Office of the Historian will tell you. It is also part of the cultural fabric to extol the moral virtues of this particular war, given that it destroyed a regime which essentially defines the modern conception of evil. Of course, as with everything else in history, some of this triumphalist patting ourselves on the back is white-washed. It turns out there was more support in the USA for Nazism before the war than is often remembered, including in the business arrangements of the Bush dynasty’s progenitor. This should not be too surprising given that leading medical journal editors in the USA were urging that the public be persuaded on moral grounds to adopt similar eugenics policies as the Nazis enforced in the 1930s.

In any case, the other accepted truism about this turn of events is that America, as the victorious industrial superpower, realized that its isolationism had only helped lead to the calamity. Therefore, like it or not, it must shoulder the burden of power, stand against the rising communist threat to make the world safe for democracy, and establish the Pax Americana which we have enjoyed since.

As with any good myth, much of this is true. Read more »

In the past year or so, I have started taking a lot of photos of the ground as I take my usual walk along the same route every day. This recent photo of the cobblestones of Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, showered with flower petals from nearby trees, is one of them.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Dick Edelstein

The visit by Pope Francis to Ireland in 2018 as part of the World Meeting of Families was important since it was the first one since the historic visit by Pope John Paul II in 1979, an event that drew around one and a quarter million people to a mass in Dublin’s Phoenix Park, the biggest crowd ever seen in the country, amounting to almost one-third of the population. Since then, religious feeling in Ireland had been on the wane, along with the Church’s authority over those who considered themselves Catholics, which was in a near-fatal slump. The Church was facing an uncertain future with the number of new seminarians dropping to record lows for several years.

Still, that visit in 2018 had generated certain expectations. First, a turnout of half a million people was expected in Phoenix Park, a figure that proved to be overestimated by around 400 percent. The actual turnout—some 130,000 people—was much smaller. However, that was nothing compared to the other expectation. On account of widespread cases of sexual molestation by clergy and a generalized public dissatisfaction over the failure of the church to recognise its history of abuse and make suitable reparations to the victims, many Irish people were expecting Pope Francis, given his reputation as a liberal, to issue a detailed and lengthy apology. In recent decades, public outrage about sexual abuse by clergy had been a worldwide occurrence, but the issue had special significance in Ireland, where the moral tone of the entire country since independence had been set by the Catholic church, despite its longstanding record of abuse.

Other factors affected Irish people’s expectations of a full apology from the Pope. One of these was the Magdalene laundries scandal. Throughout much of the twentieth century, thousands of Irish women had been incarcerated in Magdalene institutions, most of which were run by Catholic religious orders. The women were forced to work without pay or benefits. Despite the outrageous violation of the women’s human rights, the Irish government colluded with their detention and was complicit in their treatment. In 2011, a group called Justice for Magdalenes made a submission to the U.N. Committee Against Torture, arguing that the Irish government’s failure to deal with the abuse amounted to continuing degrading treatment in violation of the Convention Against Torture and that the state had failed to promptly investigate “a more than 70-year system of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of women and girls in Ireland’s Magdalene laundries”.

The story of the Magdalene Laundries was still reverberating in the public consciousness when in March 2017 Ireland was shocked by the discovery that, between 1925 and 1961, the bodies of 796 babies and young children had been interred in the grounds of the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, County Galway, many in a septic tank. Catherine Corless, the local historian who exposed the scandal, complained to Irish legislators that nothing had been done to exhume the bodies after her research came to light despite expressions of “shock and horror” from the Government and the President. Instead, the site had been returned to its original condition. As with the Magdalene scandal, the authorities initially showed unimaginable insensitivity and cruelty towards affected families.

Thus, when Pope Francis came to visit in August 2018, Irish people expected a full and sincere apology because of his reputation for sympathy towards a number of liberal causes, his commitment to the protection of vulnerable people, and on account of a series of special circumstances in Ireland. But surprisingly, no sufficiently firm apology was forthcoming. Read more »

by Rachel Robison-Greene

In my youth I used to play in the wooded area behind my parent’s house in a space that seemed, from the vantage point of a child, to be vast. Those areas exist now only in precious cloudy corners of my memory. In the external world, they have long been replaced by housing developments and strip malls. Then, rain or snow may have threatened to keep me indoors. Now the children are kept inside by fire season, when the air is toxic, the sun is some new color, and the nearby mountains disappear from view. “Fire season has always existed”, I am told, and some people believe it.

I was taught that the structure of the government of the United States would prevent any one branch from exerting tyrannical power over the people. Elected officials craft legislation and well-qualified, appointed judges protect against the tyranny of the majority. “Judges can’t stand in the way of the will of the President” and “this country has never been a democracy”, I am told, and some people believe it.

The political climate is changing faster than many of us can absorb, and we are left wandering the woods during fire season without any visible and reliable points of reference to guide us home. We can only hope that we leave the fog resembling the people we were when we entered it. I find myself wondering which changes I’ll be willing to accept. Will I come to regard some of my values as relics of a bygone era and will I be forced into that position by a sheer will to survive? Is this change in myself something to be feared?

It is a painful but common feature of the human experience to be afraid of our own capacity for change. As Jean Paul Sartre puts the point, “if nothing compels me to save my life, nothing prevents me from precipitating myself into the abyss.” I may experience fear at the prospect that I may be pushed from the cliff, but I feel anguish at the possibility that, when I find myself at the cliff’s edge, I might jump. Perhaps more disturbingly, I might find myself changing in fundamental ways that I currently find unacceptable. Should I spend my time fearing that possibility? Read more »

by Malcolm Murray

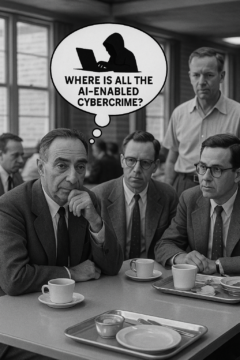

Enrico Fermi famously asked – allegedly out loud over lunch in the cafeteria – “Where is everybody?”, as he realized the disconnect between the large number of habitable planets in the universe and the number of alien civilizations we actually had observed.

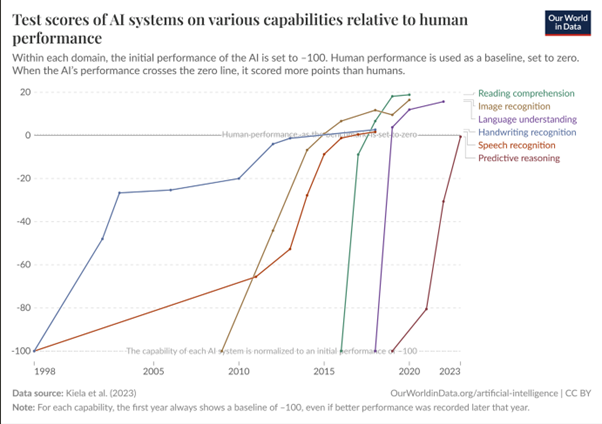

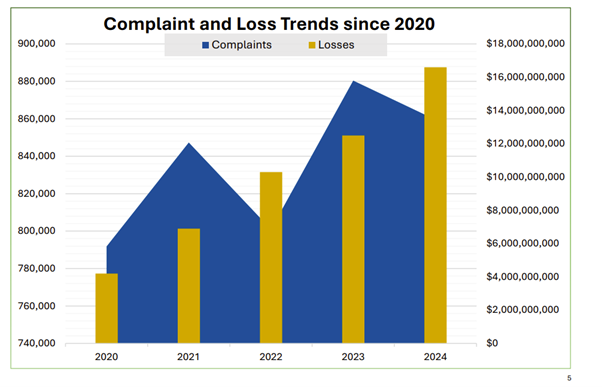

Today, we could in a similar vein ask ourselves, “Where is all the AI-enabled cybercrime?” We have now had three years of AI models scoring better than the average humans on coding tasks, and four years of AI models that can draft more convincing emails than humans. We have had years of “number go up”-style charts, like figure 1 below, that show an incessant growth in AI capabilities that would seem relevant to cybercriminals. Last year, I ran a Delphi study with cyber experts in which they forecast large increases in cybercrime by now. So we could have expected to be seeing cybercrime run rampage by now, meaningfully damaging the economy and societal structures. Everybody should already be needing to use three-factor authentication.

But we are not. The average password is still 123456. The reality looks more like figure 2. Cyberattacks and losses are increasing, but there is no AI-enabled exponential hump.

So we should ask ourselves why this is. This is both interesting in its own right, as cyberattacks hold the potential of crippling our digital society, as well as for a source of clues to how advanced AI will impact the economy and society. The latter seems much needed at the moment, as there is significant fumbling in the dark. Just in the past month, two subsequent Dwarkesh podcasts featured two quite different future predictions. First, Daniel Kokotajlo and Scott Alexander outlined in AI 2027 a scenario in which AGI arrives in 2027 with accompanying robot factories and world takeover. Then, we had Ege Erdil and Tamay Besiroglu describing their vision, in which we will not have AGI for another 30 years at least. It is striking how, while using the same components and factors determining AI progress, just by putting different amounts of weight on different factors, different forecasters can reach very different conclusions. It is like as if two chefs making pesto, both with basil, olive oil, garlic, pine nuts, cheese, but varying the weighting of different ingredients, both end up with “pesto,” but one of them is a thick herb paste and the other a puddle of green oil.

Below, I examine the potential explanations one by one and how plausible it is that they hold some explanatory power. Finally, I will turn to if these explanations could also be relevant to the impact of advanced AI as a whole. Read more »