by Barry Goldman

When I get up in the morning I drink a pot of coffee and read the paper. The coffee makes me irritable. The paper makes me furious and miserable. That sets the tone for the rest of the day.

I agree with Ezra Klein that the constitutional crisis is not coming, it is here. When the Trump administration can ignore a unanimous ruling of the Supreme Court, the breakdown of the rule of law is not threatening, it has arrived.

I am a lawyer. I speak the language. I faithfully listen to Talking Feds and Strict Scrutiny, and I read the relevant Substacks. But I’m afraid all the smart lawyers in all those places are making the same mistake. The Trump people don’t give a damn about the definition of “invasion” or “predatory incursion” under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. And they don’t give a damn about the difference between “facilitate” and “effectuate” in the Supreme Court’s order in the Abrego Garcia case. Arguing about legal definitions with Trumpers is playing chess with a pigeon. The pigeon knocks over the pieces, shits on the board, and struts around like he won. Pigeon chess has nothing to do with chess, and Trump administration litigation has nothing to do with law. This realization accounts for what I have taken to calling my macrodepression.

When I’m done with the paper and my daily dose of legal commentary, I sit down at my desk and toggle to microdepression. I look at my email. Inevitably, the people I’m looking forward to hearing from have not written. The people who have written are either cancelling something it took weeks to schedule, trying to sell me something I don’t want, or writing to tell me another one of my friends is sick or dead.

Then the phone starts ringing. Read more »

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025.

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025. Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

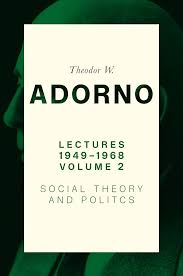

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics.

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics. About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an

About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an  Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.