Airplane shoots out from behind a mountain in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Airplane shoots out from behind a mountain in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by John Allen Paulos

As atrocious, appalling, and abhorrent as Trump’s countless spirit-sapping outrages are, I’d like to move a little beyond adumbrating them and instead suggest a few ideas that make them even more pernicious than they first seem. Underlying the outrages are his cruelty, narcissism and ignorance, made worse by the fact that he listens to no one other than his worst enablers. On rare occasions, these are the commentators on Fox News who are generally indistinguishable from the sycophants in his cabinet, A Parliament of Whores,” to use the title of P.J. O’Rourke’s hilarious book. (No offense intended toward sex workers.) Stalin is reputed to have said that a single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic. Paraphrasing it, I note that a single mistake, insult, or consciously false statement by a politician is, of course, a serious offense, but 25,000 of them is a statistic. Continuing with a variant of another comment often attributed to Stalin, I can imagine Trump asking, “How many divisions do CNN and the NY Times have.”

As atrocious, appalling, and abhorrent as Trump’s countless spirit-sapping outrages are, I’d like to move a little beyond adumbrating them and instead suggest a few ideas that make them even more pernicious than they first seem. Underlying the outrages are his cruelty, narcissism and ignorance, made worse by the fact that he listens to no one other than his worst enablers. On rare occasions, these are the commentators on Fox News who are generally indistinguishable from the sycophants in his cabinet, A Parliament of Whores,” to use the title of P.J. O’Rourke’s hilarious book. (No offense intended toward sex workers.) Stalin is reputed to have said that a single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic. Paraphrasing it, I note that a single mistake, insult, or consciously false statement by a politician is, of course, a serious offense, but 25,000 of them is a statistic. Continuing with a variant of another comment often attributed to Stalin, I can imagine Trump asking, “How many divisions do CNN and the NY Times have.”

I note that his brutish actions and policies are supplemented almost hourly by his scrofulous postings on his Truth Social platform. They, in effect, constitute a kind of denial of service attack on news coverage by reputable platforms and sites. A so-called “denial of service” attack is employed by hackers to overwhelm a website with so many requests and bits of information that the site can’t respond and shuts down. It may be a bit of a stretch, but we’re a bit like the websites that shut down when overwhelmed. Our attitude too often is that the relentless stream of nonsensical rants spewing out of Truth Social is “just” Trump talking, rather than that it’s methodically Trump undermining American democracy. The belief that “He’s all talk, don’t worry” is Intended to be reassuring, but it may be the most dangerous counsel of all.

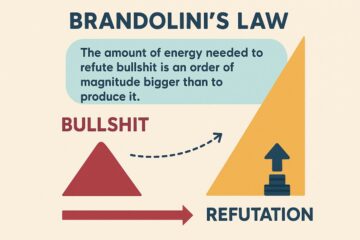

All the more reason to find anodyne advice dangerous is provided by Brandolini’s Law of Refutation. It’s a profound idea whose formulation is due to the Italian programmer Alberto Brandolini. Sometimes described as the bullshit asymmetry principle, it states, “The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.” (Brandolini wrote that the principle was inspired by the late Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow.) It might also be thought of as implying that insanity, inconsistency, and untruths are the likely destinations of political discourse if we don’t expend the considerable energy needed to insure sanity, consistency, and truth. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

‘Philosophy is a prolonged meditation on death’, so starts what may well be Mark C. Taylor’s 35th book, After the Human. A Philosophy of the Future, published by Columbia University Press. I must admit that I didn’t know Taylor’s work before reading this book, though this is perhaps unsurprising, as for most of his career Taylor seems to have focused on the study of topics and thinkers that are not particularly close to my own interests. This remains somewhat the case in After the Human: there is some discussion of Descartes and Kant – so, yea! – but there is far more of Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Derrida – a big nay.

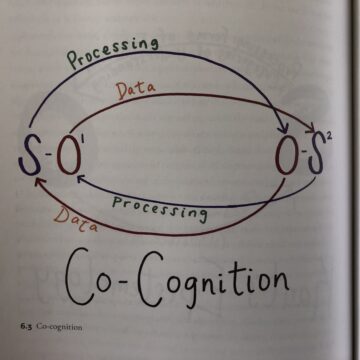

At the same time, Taylor devotes the bulk of his book to arguing that cognition is widespread in the world, from humans and other animal species to even plants and computer programmes, and all things cognitive are clearly up my street (by cognition Taylor means information processing tout court; more below). And yet most of the discussion keeps coming back to Hegel and co., even though most of the evidence, and some of the arguments, pertain to cognitive science proper and engaging with some of the contemporary literature in the philosophies of psychology and cognitive science would have been more fruitful considering the final result on display. I think this constitutes a missed opportunity.

I also think that in the end the book fails to deliver what it promises – a philosophy of the future – and instead God sneaks up on us quite unexpectedly at the very end, for no apparent reason (I should add that religion is one of Taylor’s areas of expertise, though it doesn’t feature all that much in the book). Before getting to the actual contents of the book, though, I would say that the volume could have done with a different style of argumentation.

The book is fairly eclectic, with various personal recollections intermixed with plenty of long quotes from a great number of thinkers and scholars. It is quite hard to keep up with, and keep track of, Taylor’s myriad references, points, and asides, and the presentation clearly could have benefited from a bit of signposting (oddly enough, though, the book is quite repetitive at times). In addition, and this may well be a personal shortcoming, I fear I missed out on a number of important points here and there, especially in relation to the many quotes from Hegel and company. I didn’t feel like a great many of these quotations helped the reader much or were added for the elaboration of a particular argument, but rather they were in there for exposition purposes and one needed to be acquainted with the ideas referred to already in order to understand them – and to understand how they fit in within the overall story Taylor wants to tell. Read more »

by Scott Samuelson

The sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room. —Blaise Pascal

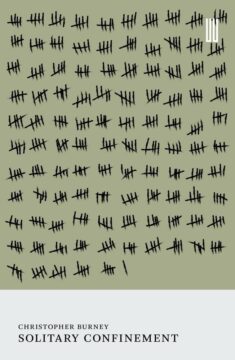

In its “Recovered Books Series,” Boiler House Press has just republished Christopher Burney’s Solitary Confinement, originally released in 1951, a profound, steely, and even sometimes funny account of the five-hundred and twenty-six days the author spent in a Nazi prison cell during World War II. Ted Gioia, who’s written a preface to the new edition, calls it “one of the great masterpieces of contemplative literature.” Even though I’ve made a point of exploring the masterpieces of contemplative literature, I hadn’t heard of Solitary Confinement until a few weeks ago. Given its publishing history, it seems that the book’s fate is to be praised as a masterpiece (by luminaries like Roberto Calasso and Frank Kermode), fall immediately into oblivion, and then be rediscovered a decade or so later—only to go through the same cycle all over.

The backstory of Solitary Confinement has the makings of a good movie. Christopher Burney (1917-1980) was born in England to upper-class parents, spent part of his childhood in India, dropped out of school at the age of sixteen (shortly after his beloved father keeled over from a heart attack around the tea table), and then wandered around Europe for a few years picking up languages. Because Burney had learned to speak French idiomatically without an accent, the British army enlisted him as a secret agent during the war. Blind-dropped into occupied France, he made his way to a crew of fellow operatives to disrupt German supply lines. When it was discovered that a double agent had infiltrated his group, Burney attempted to flee to Spain with the Nazis in hot pursuit. Surprised in his sleep by Abwehr agents who were tipped off by a hotel clerk, he was thrown into solitary confinement at Fresnes Prison in the south of France.

His cell was just ten feet long by five feet wide. The space was mostly taken up by a bed and a small table, which he turned on their side during the day to do exercises and walk back and forth. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

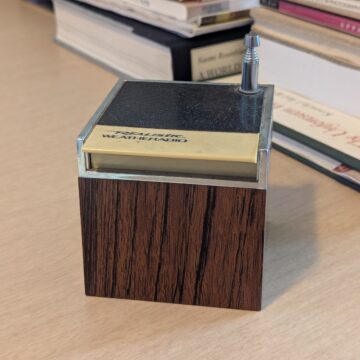

After my power went out during a recent round of severe storms, I turned on my battery-operated Realistic Weatheradio. I bought this cubical radio at Radio Shack many years ago, and it sits on a bookshelf in the living room, largely ignored until extreme weather happens along. It can be tuned to one of two wavelengths on which the National Weather Service broadcasts a loop of information on current and predicted weather conditions. It has a large, obvious on-switch; the two dials on the bottom are labeled “Tuning” and “Volume.”

When I turned the radio off after the storms had moved on, it occurred to me that it would probably look very old-fashioned to young people; I was thinking of my grandchildren and nieces and nephews. The sides are covered in wood veneer, a nod to the fact that radios used to be pieces of wooden furniture. I wondered if anyone else still uses a radio that you tune with a dial. For some reason, the radio was defamiliarized so that even to me it seemed to be slightly out of place in time. (I feel that way myself sometimes.) And it unexpectedly conjured an entire lost world.

I looked up the Weatheradio and learned that it was sold between 1982 and 1992. Realistic was a house brand of Radio Shack, which for many years sold consumer electronics. It was a standard fixture of malls in my youth, like Orange Julius and WaldenBooks. In 2015, the company declared bankruptcy, in part because it couldn’t compete well as the market for electronics—in fact, the nature of consumer electronics—changed dramatically. It changed hands several times and is currently an online business called RadioShack (losing a space in its name, among many other things). The only actual radios it currently sells are four models of a vintage three-band radio (AM, FM, shortwave). (So I guess there are other people who tune their radios using a dial.) It’s a familiar story, and it encapsulates one of the ways the world has changed in my lifetime.

I can’t remember when I bought my radio, but my life has also changed considerably since the decade it was on the market. Seeing the weather radio as a vintage object brought home to me how many things that used to be familiar have vanished. I don’t miss Radio Shack, or malls, and I don’t particularly mind that some of the more recent technology I use is now considered vintage. But sometimes it feels as if the world has moved on and left me behind. I’ve always been a bit of an oddball, but the world I learned to adapt myself to was the one I grew up in, and that world is largely gone. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013.

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Richard Farr

It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

Others are waving the Ukrainian or Canadian flag. Or Hire a Clown and Get a Circus. Or Support Our Troops: Fire Hegseth. In my small town we’re perhaps 2% of the population — not yet one of those mass movements to which the future’s textbooks will devote a chapter, but we are fearful enough to need the hope of that outcome. With America’s vaunted institutions and much-hyped freedoms on fire, we desperately want more people to (as one of my own signs says) Join Us Before It’s Too Late.

We try to take comfort from the fact that we occupy three corners of the intersection, greatly outnumbering the Trumpers, a dozen people blasting patriotic country music on the northwest corner. But we know the truth: the only consequence of our protests, at least until ICE comes to town and starts handing out free tickets to El Salvador, is that it buys us a little dignity, a little solidarity, a little courage in the face of disaster.

Some of us are “leftists,” which is American English for “centrist neoliberals who look back wistfully to the era of Barack and Hillary.” Some are “radical leftists,” which is American English for “people so naïve that they actually care about things like climate change, the minimum wage, Citizens United, Gaza, nuclear command and control, universal healthcare, starving Yemeni children, and Ukraine.” All of us are appalled that Donald Trump and his one-eyed yellow minions are vandalising central functions of the state, especially the ones that involve anti-corruption oversight.

So that makes us the statists and him the anarchist, right? Read more »

What happens, happens before & after,

every time, without fail, always— yet, is singular,

is a one-note affair in a symphony of nows

each moment of which then becomes

before & after, simultaneously.

If this seems confusing, blame time,

or life, or God which, in particular,

has been a widespread explanation

of the fact-of-being during millennia

of befores & afters since the

beginning-was-the-word,

and the word was,

………………………… Now

and always is.

But this is not an explanation,

nor was it meant to be anything

more than a statement of fact,

that of the breadth and depth

of our life-long ignorance of,

why being?

Jim Culleny

6/1/25

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Gary Borjesson

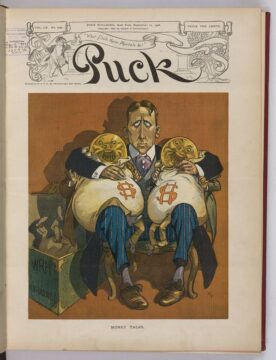

And these two [the rational and spirited] will be set over the desiring part—which is surely most of the soul in each and by nature the most insatiable for money—and they’ll watch over it for fear of its…not minding its own business, but attempting to enslave and rule what is not appropriately ruled by its class, thereby subverting everyone’s entire life. —Plato’s Republic 442a

I want to share my vision for a tool that helps inform, direct, and scale consumer power.

It would be a customized AI that’s free to use and accessible via an app on smartphones. At a time when many of us are casting about for ways to resist the corruption and authoritarianism taking hold in the US and elsewhere, such a tool has enormous potential to help advance the common good. I’m surprised it doesn’t already exist.

Why focus on consumer power? Because politics in the US has largely been captured by monied interests—foreign powers, billionaires, corporations and their wealthy shareholders. Until big money is out of politics (and the media), to change the country’s social and political priorities we will need to encourage corporations and the wealthy to change theirs.

As Socrates observed in the Republic, these “money makers” operate in society like the appetitive part operates in our souls. This part seeks acquisition and gain; it wants all the cake, and wants to eat it too. If unregulated, this part (perfectly personified by Donald Trump) acts selfishly and tyrannically, grasping for more, bigger, better, greater everything—and subverting the common good in the process.

The solution, as Socrates saw, is not to punish or vilify this part, but to restrain and govern it, as we do children. For the more spirited (socially minded) and rational parts of ourselves and society recognize the justice and goodness of sharing the cake. Thus the AI I envision will have a benevolent mindset baked into its operating constraints. But before seeing how this might work, let’s consider how powerful aggregated consumer spending can be. Read more »

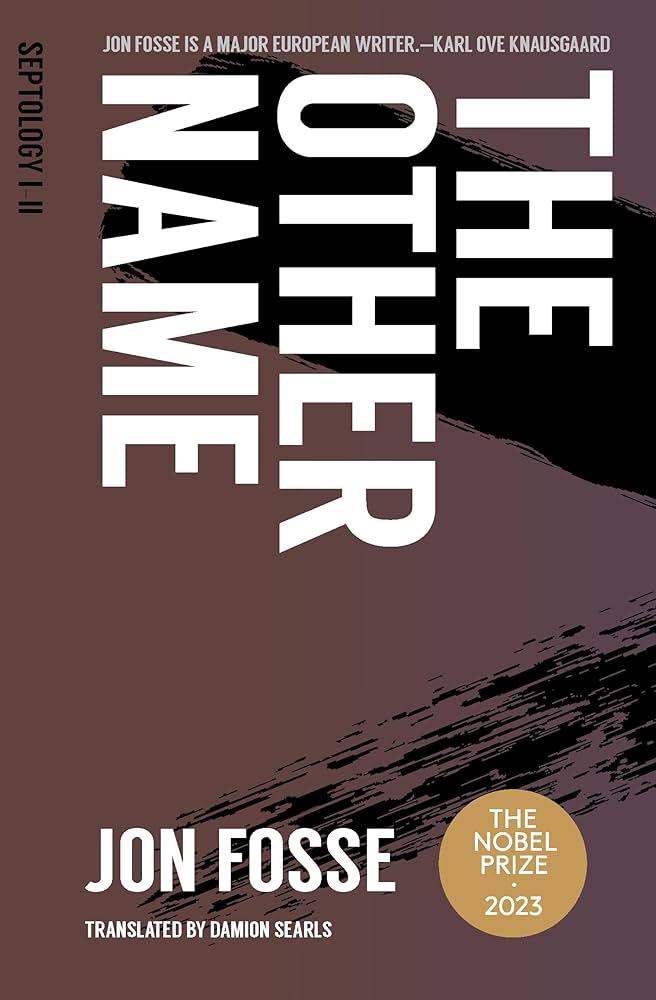

by Derek Neal

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

So this is how the words work, but what do they say? After reading the first two books in the collection, which together are called The Other Name, the best way I can explain it is by quoting a passage from the book itself:

and that’s how it also is with all the paintings by other people that mean anything to me, it’s like it’s not the painter who sees, it’s something else seeing through the painter, and it’s like this something is trapped in the picture and speaks silently from it, and it might be one single brushstroke that makes the picture able to speak like that, and it’s impossible to understand, I think, and, I think, it’s the same with the writing I like to read, what matters isn’t what it literally says about this or that, it’s something else, something that silently speaks in and behind the lines and sentences (italics mine)

The narrator who is talking, an elderly painter named Asle who lives in rural Norway, spends much of the book like this, thinking about his paintings and trying to explain what they mean. He is unable to explain their meaning, however, because language and painting are two different things, and something gets lost in translation. What he says about writing takes things even further, suggesting that words don’t mean what we say they mean—“what matters isn’t what it literally says about this or that, it’s something else, something that silently speaks in and behinds the lines and sentences.” I would like to suggest that this is the true subject of Fosse’s book (or at least the first two that I’ve read), the idea that words do not mean what we say they mean, but something else, something behind the words.

Fosse’s challenge, of course, is to express this idea through language. How do we say one thing with words that mean something else? Read more »

by Barry Goldman

The brilliant and recently departed Jules Feiffer drew a cartoon many years ago called Munro. It was later made into an Academy Award-winning animated short. You can watch it here.

Munro was only four years old, but somehow he got drafted into the army. He went to see his sergeant and said, “I’m only four.” The sergeant said:

It is the official policy of the army not to draft men of four. Ergo you cannot be four.

We see this form of reasoning in many contexts. It is the official policy of the United States that we do not torture prisoners of war. Therefore, waterboarding, which has been used to torture prisoners since the 14th century, cannot be torture.

Alternatively, the prisoners captured after 9/11, detained at Guantanamo, and waterboarded regularly cannot be “prisoners of war.” Instead, they are “alien enemy combatants” to whom the protections of the Geneva Convention do not apply.

This kind of reasoning can be difficult and complex and may require many years of rigorous training. Only a highly-trained and rigorous thinker like John Yoo, now the Emanuel S. Heller Professor of Law at UC Berkeley, could produce a document like Military Interrogation of Alien Unlawful Combatants Held Outside the United States. Try to read it and you will see.

My point is: This is what lawyers do. As the Devil’s Dictionary put it:

LAWYER, n. One skilled in circumvention of the law.

But there is a larger point that is both more important and less discussed. Even if there were a clear and unambiguous law, duly approved by Congress and signed by the president that said “Torturing prisoners is perfectly fine,” it would not be fine. If anything is wrong, torture is wrong. It doesn’t matter what Mr. Yoo or Congress or the President says. An atrocity enacted into law does not cease to be an atrocity. Read more »

by Rachel Robison-Greene

Many people who have thought carefully about AI are anxious about certain uses of it, and for good reason. Many are concerned that people (young people in particular) are increasingly offloading their critical thinking development and responsibilities to Chat GPT and other large language learning models. We may fail to flourish as citizens, neighbors, and friends because we allow AI to do so many of the tasks that would otherwise prepare us for the challenges we’ll encounter in our lives. That said, some applications of AI seem like they offer tremendous benefits. For example, there is promising research being done into using AI models to understand non-human language. Doing so will help us to better understand non-human consciousness. This has the potential to change how we see and treat other animals and how we view ourselves as members of biotic communities.

Some AI companies, such as the Chinese company Baidu are looking to fulfill very human impulses. Their products focus on deciphering the communication of companion animals such as cats and dogs. What pet caretaker wouldn’t be interested in knowing what their furry friends are trying to communicate? Other AI applications focus on the communication patterns of big-brained animals such as sperm whales. These creatures engage in an impressive amount of vocalization and there is good reason to believe that mapping whale sounds can tell us all sorts of important things about the mental and social lives of whales. These scientific advances have the potential to finally pull us out the philosophical rut we’ve been in with respect to animal minds for the entire history of human philosophical engagement. Read more »

by Eric Schenck

My sister and I have always been close. But for the last few years, something has bonded us like nothing before: trashy television. We love nothing more than to watch reality TV shows and rejoice that we are not these people.

90 Day Fiancé (hereafter affectionately referred to as 90 Day) is one of those shows. The premise is simple: people find each other (usually an American and non-American, typically online), develop some kind of virtual relationship, and then finally meet up in person.

The name comes from the “K-1 visa”. This legally gives a foreigner 90 days to get married to a U.S. citizen after they have entered the country if they want to stay. For our delight at home, that’s usually when things go to shit.

There are different versions of 90 Day, but no matter which one we watch, one truth remains: the show really is a master class in love. Not necessarily what you should do to ensure a healthy relationship – but what you should avoid at all costs.

What follows are 20 lessons in love that 90 Day Fiancé has taught me. I hope you learn as much as I have! Read more »

by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

You are scrolling through photos from your childhood and come across one where you are playing on a beach with your grandfather. You do not remember ever visiting a beach but chalk it up to the unreliability of childhood memories. Over the next few months, you revisit the image several times. Slowly, a memory begins to take shape. Later, while reminiscing with your father, you mention that beach trip with your grandfather. He looks confused and then proceeds to tell you that it never happened. Other family members corroborate your father’s words. You inspect the photo more closely and notice something strange, subtle product placement. It turns out the image was not really taken by a human. It had been inserted by a large retailer as part of a personalized advertisement. You have just been manipulated into remembering something that never happened. Welcome to the brave new world of confabulation machines, AI systems that subtly alter or implant memories to serve specific ends. Human memory is not like a hard drive, its reconstructive, narrative, and deeply influenced by context, emotion, and suggestion. Psychological studies have long shown how memories can be shaped by cues, doctored images, or repeated misinformation. What AI adds is scale and precision. A recent study demonstrated that AI-generated photos and videos can implant false memories. Participants exposed to these visuals were significantly more likely to recall events inaccurately. The automation of memory manipulation is no longer science fiction; it is already here.

I have had my own encounter with false memories via AI models. I have written and talked about my experiences with the chatbot of my deceased father. Every Friday whenever I would call him, he would give me the same advice every time in the Punjabi language. In the GriefBot, I had transcribed his advice in English. After I had interreacted with the GriefBot for a few years, I caught myself remembering my father’s words in English. The problem is that English was his third language and we seldom communicated in English and certainly never said those words in English. Human memory is fickle and easily reshaped. Sometimes, one must guard against oneself. The future weaponization of memory won’t look like Orwell’s Memory Hole, where records are deleted. It will look more like memory overload, where plausible-but-false content crowds out what was once real. As we have seen with hallucinations, generation and proliferation of false information need not be intentional. We are likely to encounter the same type of danger here i.e., unintentional creation of false memories and beliefs through the use of LLMs.

Our memories can be easily influenced by suggestions, imagination, or misleading information, like when someone insists, “Remember that time at the beach?” and you start “remembering” details that never occurred. People can confidently recall entire fake events if repeatedly questioned or exposed to false details. Read more »

by Thomas R. Wells

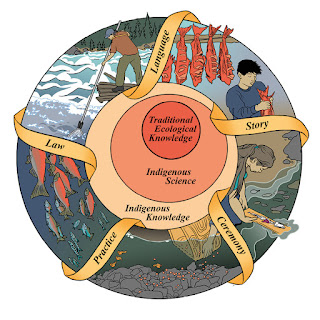

The idea that ‘indigenous’ knowledge counts as knowledge in a sense comparable to real i.e. scientific knowledge is absurd but widely held. It appears to be a pernicious product of the combination of the patronising politics of pity and anti-Westernism that characterises the modern political left (dumb, but still preferable to the politics of cruelty that characterises the modern political right!).

My point is simple: knowledge is knowledge. Where it comes from doesn’t matter to its epistemic status. What matters is whether it deserves to be believed. The scientific revolution has provided a general approach – systematic inquiry – together with specialist methodologies appropriate to different domains (such as mathematical modeling, taxonomy, statistical analysis, and experimental manipulation and measurement). It is irrelevant that this approach first appeared in North-Western Europe and that many of the domain specific techniques were first developed and refined by white men from the ‘west’. What is relevant is that modern science allows a degree of confidence in factual and theoretical claims that has never been warranted before, and made this capability equally available to everyone around the world as the new standard for objective knowledge, i.e. knowledge that is reliably true no matter from what perspective you look at it.

If indigenous peoples have observational data and successful technologies to contribute to this kind of systematic inquiry into what makes an ecosystem resilient, or what plants might contain molecules with pain-relieving properties, or the history of climactic events, then that should be welcomed. But the test of whether these are an actual contribution must come from whether they survive scientific scrutiny, not the authenticity of their indigenous origins.

Center of a peony in Vahrn, South Tyrol. Happy Spring!

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Kevin Lively

Introduction

It is a well-worn observation that a sense of fatalism seems to be settling across the peoples of the world. There is a wide-spread feeling that global developments are echoing trends from the 1930s. Economic centers in the USA are gearing up their domestic industrial capacity, while the defense department speaks of Great Power Competition. China does the same, while trenches and mines scar the fields of Ukraine. With the NATO alliance under question, Europe begins to look after its own industrial base while refugees from drought-stricken, strife-torn lands drown in the Mediterranean. Those who manage a safe arrival, both in Italy as in Texas, often struggle to integrate into an aging society despite a desperate need for young workers. Substantial and growing fractions of the US and European populations are of the mind that this influx of hands — ready and eager to work — should not be turned to repairing crumbling bridges or staffing overworked retirement homes. Rather they should be banished and sent away in disgrace, regardless of the final destination.

An unspoken thought seems to be flowing among the currents beneath many people’s minds. More and more often now, it seems to break to the surface at unexpected times. Here’s a drinking game: every time you hear some variation of the phrase “in today’s geopolitical climate”, take a shot. Depending on where you work and what topics your lunch conversations drift towards, it may be unwise to play this game on a weekday. These events increasingly beg for certain pressing questions to be asked.

For example: how do we, as a species, deal with these dislocations of people, and the disruptions to their means of supporting themselves? How do we, as a species, plan for the future dislocations to come, as crop cycles grow increasingly unpredictable and failure-prone, while the ocean’s fish are replaced with plastic as ever more forms of pollution with unknown consequences accumulates? How do we, as a species, allocate this planet’s apparently dwindling resources between ourselves in order support a simple life of dignity and peace, unburdened by the deprivation of extreme poverty and the chaos it brings?

Discussions around such questions are, by necessity, discussions of death, religion, power and land — among the topics best avoided both at Thanksgiving and a bar. Thus there is a tendency to tread carefully around them while in polite company. Yet in today’s geopolitical climate it increasingly behooves us all to address such questions in a sober and critical manner. Ideally we should all have some mutually understood context for the stage on which these events are playing out, whether we’re in the audience, on the gantry or elsewhere, busy prepping the smoking lounge in your bunker. Read more »

by Dick Edelstein

According to today’s newspaper, Spain is expected to lose some 30% of its population over the next 75 years, based on current birth rate projections, a loss of over eight million inhabitants—too great to cover through the influx of migration (La Vanguardia, 17 May). And what about other European countries? The study cited above predicts a still greater per capita drop in Italy’s population. So why aren’t people more worried about who will supply the labor power that we will need to secure future social benefits, rather than heeding absurd declarations by right wing populists like Meloni and Trump on the supposed dangers of migration?

At a time when it is essential to be able to separate the facts and realities of migration from the myths and lies, author Ian Goldin offers us timely assistance in a brief book entitled The Shortest History of Migration, an indispensable guide when the facts of migration are obscured by a baseless hysteria whose effects span the political spectrum, influencing the attitudes of groups and individuals on the left as well as the right. This is an opportune moment to take a good look at those facts. The author, with a gift for synthesizing detailed material, has produced a concise book, with an apt cover blurb that says: “Read in a day. Remember for a lifetime.” Goldin takes a very long view, explaining to readers how migration has always been an intrinsic part of the evolution and development of the human race as he traces the phenomenon throughout all of the eras of human history.

As a migrant myself, and someone whose recent ancestors migrated from Europe to the New World for some of the reasons succinctly described in this book, for me this is a personal as well as a social question, although most people have some personal interest in migration as well as their own viewpoint. Read more »