by Laurie Sheck

1.

Years ago, when my daughter was five, we spent a day at the Barcelona Zoo. As I held her small hand in mine, we stood before a cage in which a large albino gorilla resolutely turned his face from us. If we moved to the right, he turned his face to the left, if we edged toward the left, he shifted to the right. He was determined to have no eye contact with us, and at that moment I felt ashamed. My very presence, my gaze, was a kind of violation. I was in the presence of a being, dignified and exposed, with whom I had no shared language apart from the mute language of gesture. His own stark language was deeply expressive, and his refusal said the most basic things about captivity, inequality, exposure, isolation.

In his 1977 essay Why Look At Animals? John Berger traced the increasing estrangement between animals and humans: “The 19th century, in western Europe and North America, saw the beginning of a process, today being completed by 20th century corporate capitalism, by which every tradition which has previously mediated between man and nature was broken. Before this rupture, animals… were with man at the center of his world.” Picture the early cave paintings, how sensitive they were to the curve of an animal’s back, its grace and power, its sense of movement.

Berger goes on to think about how in the intimate gaze exchanged between animals and humans, now so often lost, there is a sense of both recognition and mystery, knowing and unknowing. And how, within this relationship, “The animal has secrets which, unlike the secrets of caves, mountains, seas, are specifically addressed to man.” How it is hubris to forget this mixture of what can be grasped and what is secret and other. And now, in the 21st century, it is all too easy to experience animals as images in children’s picture books, cartoon characters, and commodities produced by factory farms. Yet it seems there still lingers a haunting feeling of intimacy and betrayal, a painful and also beautiful, almost sacred, sense of vulnerable, complex lives that are not confined to “owner” and “owned” or to commodity and consumer.

2.

It is night, I am sitting in my study. My daughter is grown now, the pandemic has been raging for two years. There is a silence that is hard to name—isolate, almost wounded. And in this silence, in this dim light, I pick up a book about a dog I have only ever vaguely heard about, a dog known mostly as an image on a stamp or coffee cup or watch-face, reduced and cartoonish.

The dog is Laika, the first mammal to be sent into outer space.

And as I think of her, I think again of Berger’s essay. How he said that in our modern world, “Animals appear like fish seen through the plate glass of an aquarium…. The fact that they can observe us has lost all significance…. What we know about them is an index of our power.”

This dog sent into outer space— I want to know who she was, to have some sense of what her life was, what she felt. But I know I can never really know. All I have are a few facts. Read more »

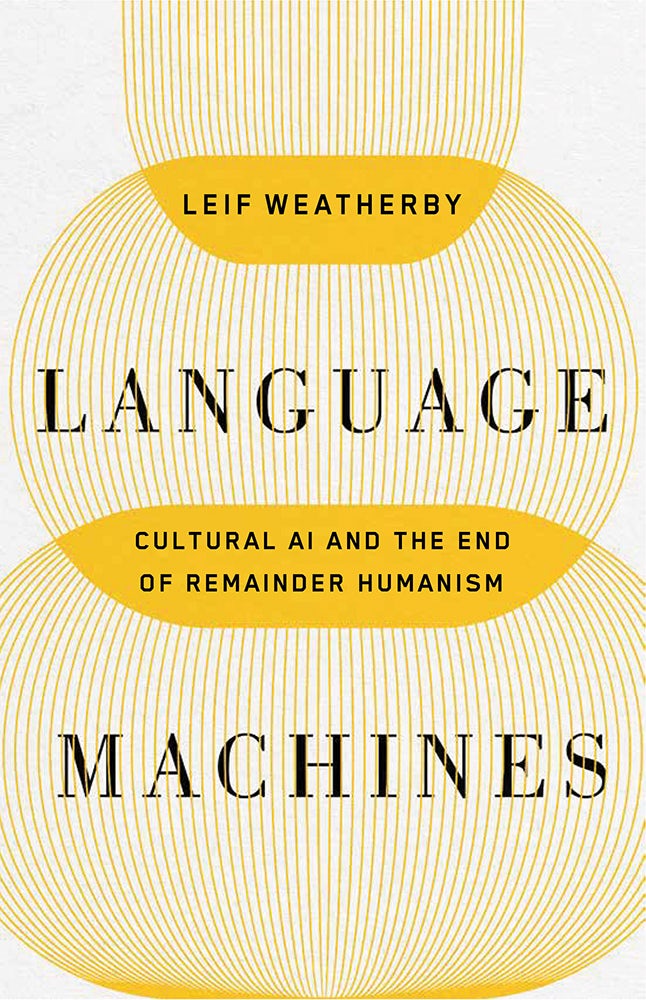

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019.

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019. At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect.

At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect.