by Ed Simon

Demonstrating the utility of a critical practice that’s sometimes obscured more than its venerable history would warrant, my 3 Quarks Daily column will be partially devoted to the practice of traditional close readings of poems, passages, dialogue, and even art. If you’re interested in seeing close readings on particular works of literature or pop culture, please email me at [email protected]

Poetry is nothing more than the arrangement of words on a page. Verse’s defining attribute is the line-break. Obviously, there are sharp objections that could be made to those two interrelated contentions, not least of which is the incontrovertible fact that before poetry was a written form it was an oral one, and line breaks make no sense in the later medium (though the equivalent of spoken pauses certainly do). Nonetheless, written poetry has existed for millennia, and it’s impossible not to interpret “poetry,” as a form, through its primarily written permutations. Oral and written poetry now exist in tandem, and it’s a psychic nonstarter to imagine the former without the existence of the later. Furthermore, the revolution in first blank verse and then free verse that forever allowed for the possibility of writing poetry without all of the standard accoutrement of rhetorical defamiliarization which defines the form, from assonance to consonance, meter to rhythm, and of course rhyme, had led to the visual arrangement of poetry on a page as the standard indication that what you’re reading is indeed verse and not prose.

Arguably line-breaks, particularly in the form of enjambments, provide a particular form of linguistic defamiliarization that distinguishes poetry from prose because it heightens readers’ expectations concerning meaning. Russian Formalist critic Viktor Shklovsky in his 1917 essay Art as Technique writes that poetry serves “to make things ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms obscure, so as to increase the difficulty and the duration of perception.” Shklovsky defined poetry as being that which makes language unfamiliar through a variety of conceits, only some of which could be considered traditionally “poetical” (though all of those methods can be excellent in achieving that defamiliarization). Line breaks work to “increase the difficulty and the duration of perception” precisely because they disrupt the normal reading of a line; by deferring meaning between lines, and altering the conventional and expected rhythms of meaning one would encounter in prose, a poem is able to imply particular questions or intentions in one line that are answered in the next, so that as Shklovsky writes “it is our experience of the process of construction that counts, not the finished product.”

A good example of how this particular process works is in American poet Denise Levertov’s 1958 poem “Illustrious Ancestors” from her collection Overland to the Islands. The free-verse poem (only eighteen-lines) is organized into three implied stanzas through indentions at the ninth and thirteenth lines, and concerns Levertov’s spiritual inheritance from the two widely divergent sides of her family. Levertov’s father was a Russian Jewish convert to Anglicanism (indeed he became a priest), descended from a long-line of Hasidic rabbis, including Rev Schneur Zalman, founder of the Lubavitch sect. Her Welsh mother’s grandfather was Angel Jones of Mold, a nonconformist Methodist mystic known for his eccentric preaching and visions. Read more »

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.

by David J. Lobina

by David J. Lobina

Hebrew or English?

Hebrew or English? Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025.

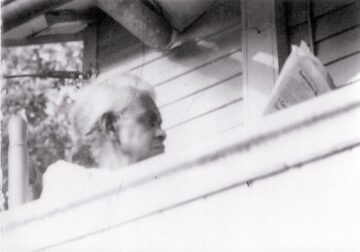

Sughra Raza. On The Rocks at Lake Champlain. August 22, 2025. reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.

reat-grandmother Emmaline might have loved it too. Born enslaved, she started anew after the Civil War, in what had become West Virginia. There she had a daughter she named Belle. As the family story has it, Emmaline had a hope: Belle would learn to read. Belle would have access to ways of understanding that Emmaline herself had been denied. We have just one photograph of Belle, taken many years later. Here it is. She is reading.