by Herbert Harris

I began my psychiatric training in 1990, the year that marked the start of a program called the “Decade of the Brain.” This was a well-funded, high-profile initiative to promote neuroscience research, and it succeeded spectacularly. New imaging techniques, molecular insights, and psychopharmacological discoveries transformed psychiatry into a vibrant biomedical science. The program brought thousands of careers, including my own, into the neurosciences.

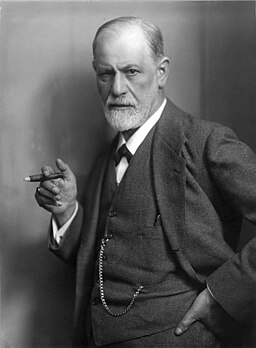

Despite its progress, the Decade of the Brain also widened an existing rift. This was the large gap between the psychoanalytic tradition and the biological sciences. The divide wasn’t new. Freud started with neurology but shifted to psychoanalysis when the brain sciences of his time couldn’t fully explain the complexities of the mind. For the first half of the 20th century, psychoanalysis was the main way to understand mental illness. Then, in the 1950s, new psychiatric drugs appeared: chlorpromazine for psychosis, lithium for mood disorders, and antidepressants for depression. For the first time, it seemed possible to treat mental illness by directly targeting the brain, rather than long-term therapy or institutional care.

By the time I was a resident, these diverging traditions had opened into a chasm. On one side was biological psychiatry, focused on neurotransmitters, neuroimaging, and cognitive-behavioral treatments, with outcomes that could be measured and tested. On the other side were psychoanalysis and its branches: attachment theory, object relations, and the investigation of unconscious conflicts through language, narrative, and symbolism. They had become separate languages, spoken within distinct professional communities, each wary of the other. There were occasional efforts at rapprochement, but little sustainable progress. By the end of the Decade of the Brain, reconciliation seemed almost impossible. I was fortunate to be in a training program that had a research track, allowing me to work in a lab, but I also had mentors who were distinguished analysts. It was like being in two different residencies.

Both have proven valuable over the years, but I never expected them to converge. However, today, circumstances appear to be shifting. A merging of neurobiology, computational neuroscience, and neuroimaging has created a new paradigm: active inference. For the first time, we can start to identify strong links between analytic models of the mind and biological models of the brain. Read more »

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take