by Brooks Riley

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Jochen Szangolies

The principal argument of the previous column was that without the possibility of making genuine choices, no AI will ever be capable of originating anything truly novel (a line of reasoning first proposed by science fiction author Ted Chiang). As algorithmic systems, they can transform information they’re given, but any supposed ‘creation’ is directly reducible to this initial data. Humans, in contrast, are capable of originating information—their artistic output is not just a function of the input. We make genuine choices: in writing this sentence, I have multiple options for how to complete it, and make manifest one while every other remains in the shadow of mere possibility.

This is of course a controversial proposition: just witness this recent video of physicist Sabine Hossenfelder making the case for free will being an illusion. In particular, she holds that “the uncomfortable truth that science gives us is that human behavior is predetermined, except for the occasional quantum random jump”. I think this significantly overstates the case, in a way that ultimately rests on a deep, but widespread misunderstanding of what science can ‘give us’—and more importantly, what it can’t.

Before I make my argument, however, I feel the need to address an issue peculiar to the debate on free will, namely, that typically those on the ‘illusionist’ side of the debate consider those taking a different stance to do so coming from a place of romantic idealization. The charge seems to be that there is a deep-seated need to feel special, to be in control, to have authorship over one’s own fate, and that hence every argument in favor of the possibility of free will is inherently suspect. I think this is a bad move. First of all, it poisons the well: any opposing stance is tainted by emotional need—just a comforting story its proponents tell themselves to prop up their fragile selves. (Hossenfelder herself describes struggling with the realization of having no free will.)

But more than that, I just don’t think it’s true—disbelief in free will can certainly be as comforting, if not more so. After all, if I couldn’t have done otherwise, I couldn’t have done better—I did, literally, my best, with everything and always. No point beating myself up about it afterwards. Read more »

by Bonnie McCune

When my grandson was about two, I heard him stirring from his nap and went to his bedroom to get him up. He saw me at the door and clambered to his feet, clinging to the rail of his crib. “I got eye blooows,” he announced with pride, indicating with a pointed finger the yellow fuzz framing one eye.

I can imagine his curiosity as he first felt the ridge frequently called the brow ridge, the bony prominence above the eyes, known also as the supraorbital ridge. Touching the hairs and wondering what in the heck they are. Asking his parents why his face sprouted these strange growths. Checking faces of people around him for similar protrusions.

A momentous discovery, probably more for me than for him. It’s difficult for adults to get any view, even a squinty-eyed one, into the mind of a child just learning about himself and life. I was lucky. This particular child, at that precise time, paired verbal skills with a questioning mind and was able to say what he was thinking. I’d never caught a glimpse of the process before although I’d wondered how a kid learns.

I’ll give you an answer. It’s the same way a kid learns about a roly-poly bug and how it faces danger. They poke at it. Go nudge something and get excited about it, learn about it. This is actually how we continue to learn about life in all its fascinating variations. We witness some phenomenon, wonder about it, and learn and think.

We don’t claim we’re always right. Aging is a particularly delicate topic. Some of us don’t want to admit we’re not as charming or beautiful or strong or healthy as we once were. So we cover up with white lies and smiles.

But how does each of us determine, and ADMIT, we’re old? Read more »

by Malcolm Murray

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

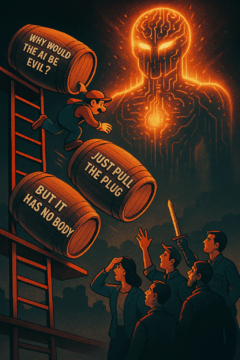

“Humans are lucky to have Yudkowsky and Soares in our corner, reminding us not to waste the brief window that we have to make decisions about our future.”— Grimes

Probably the first book with blurbs from both Ben Bernanke and Grimes, a breadth befitting of the book’s topic – existential risk (x-risk) from AI, which is a concern for all of humanity, whether you are an economist or an artist. As is clear from its in-your-face title, with If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies (IABIED), Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares have set out to write the AI x-risk (AIXR) book to end all AIXR books. In that, they have largely succeeded. It is well-structured and legible; concise, yet comprehensive (given Yudkowsky’s typically more scientific writing, his co-author Soares must have done a tremendous job!) It breezily but thoroughly progresses through the why, the how and the what of the AIXR argument. It is the best and most airtight outline of the argument that artificial superintelligence (ASI) could portend the end of humanity.

Although its roots can be traced back millennia as a fear of the other, of Homo sapiens being superseded by a superior the way we superseded the Neanderthals, the current form of this argument is younger. I.J. Good posited in 1965 that artificial general intelligence (AGI) would be the last invention we would need to make and in the decades after, thinkers realized that it might in fact also be the last invention we would make in any case, since we would not be around to make any more. Yudkowsky himself has been one of the most prominent and earliest thinkers behind this argument, writing about the dangers of artificial intelligence from the early 2000s. He is therefore perfectly placed to deliver this book. He has heard every question, every counterargument, a thousand times (“Why would the AI be evil?”, “Why don’t we just pull the plug?”, etc.) This book closes all those potential loopholes and delivers the strong version of the argument. If ASI is built, it very plausibly leads to human extinction. End of story. No buts. So far, so good. As a book, it is very strong. Read more »

by Barbara Fischkin

Eight weeks have passed since I wrote about my Cousin Bernie—and how, posthumously, he adds to my own memories of him. As readers may remember from my last offering, Cousin Bernie’s widow, Joan Hamilton Morris, sent me the pages of an incomplete memoir her late husband pecked out on a vintage typewriter in an adult education class he took after retiring as a university professor of psychology and mathematics.

If Cousin Bernie were alive today he would be 102. Those pages of memoir chapters, some more worn than others, remain in a place of honor, tucked into a corner of my own writing table. I feel that “Cousin Joanie,” as I call his widow, sent them to me for safekeeping—and for presentation to the world. Originally I thought I could do this in one or two chapters. A deeper read has revealed a surprising amount of insight. Here is my fourth take on my cousin, who fascinates me despite his evergreen persona as a nerdy, chubby, lost boy from Brooklyn. There will be a fifth offering and probably a sixth. If it seems Bernie is taking over my memoir, I am fine with this. I have written a lot about my mother’s side of the family. Now it is my father’s family’s turn. And what better way to bring them into the light, than through Cousin Bernie?

What follows is Cousin Bernie, Part Four. I’ve only edited it slightly, less so I think than his Adult Education teacher. So far, my minor editing has provoked no lightning bolts from the heavens. I have discovered another Bernie, a child who believed he could fly like his comic strip hero.

“I was eight years old, and my sister, Gertie, six. We had just been transplanted to Bridgeport, Connecticut from Brooklyn, New York. My father, a home painter and decorator, felt that he could do better in terms of finding work in a smaller city.

“Here, a whole new set of stimuli presented itself: A Benjamin Franklin stove in the kitchen, a gas water heater in the bathroom, which had to be lighted so we could bathe, and a coal bin on the back porch. There was a scuttle for bringing in coal for the stove. The Saturday Sabbath meal preparations—gefilte fish, stewed chicken and beef, challahs, cookies and pies—began as early as Wednesday night. The stove was banked and allowed to go out on Saturday night.

“We slept as the stove died down and, on Sunday mornings, my sister and I would climb into my parents’ big bed. Pop got up wearing his union suit, put on a robe, removed the ashes, kindled a new fire in the stove and came back to bed with us for my reading of the Sunday comics. My sister, Gertie, pointed to each speech bubble, as I read them. It seemed to me that Andy Gump’s nose or chin was strange looking. I disliked it when the bubbles were long. But it was here in the Sunday comics that I encountered the adventures of ‘Buck Rodgers in the Twenty-Fifth Century.’ Read more »

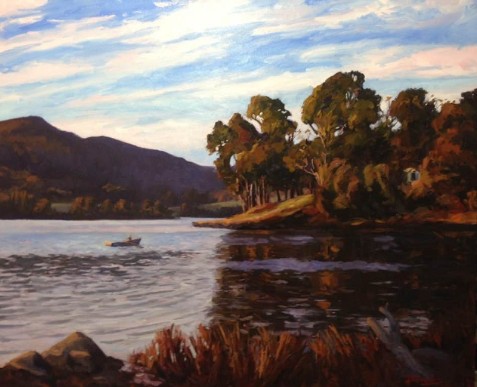

Boat:

……… —Your slope is russet and graceful; seems soft.

Land:

……… —It is. I see it echoes the grace of your gunnels, stem to stern.

Boat:

……… —We approach your still grace, having been upon water all day.

Land:

……… —Who is that with you, the who with articulating sticks?

Boat:

……… —He rows, he brings me to you to lie in your shade.

…………. He imagines the sky is worth gazing into

…………. with you beneath his back; the painter has

…………. rendered us true and sure & his clouds

…………. follow the breath of wind as they must

Land:

……… —But I’m confused, what painter,

………… I am real and true and so is sky?

Boat:

……… —Yes, and so the painter is, and so am I.

Jim Culleny, 11/16/22

Painting by Jack Braudis

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Philip Graham

Archipelago, the third novel by Natalie Bakopoulos, ranges among the Cycladic Islands of Greece, the coast of Croatia, and crosses the borders of various Balkan states until finally—temporarily?—settling in a small town in the Peloponesian peninsula. All this traveling echoes (and is echoed by) the inner journey of the unnamed (and yet named) narrator of Archipelago, a translator who, as the novel progresses, seems to allow her own self to be written, to be translated.

Archipelago, the third novel by Natalie Bakopoulos, ranges among the Cycladic Islands of Greece, the coast of Croatia, and crosses the borders of various Balkan states until finally—temporarily?—settling in a small town in the Peloponesian peninsula. All this traveling echoes (and is echoed by) the inner journey of the unnamed (and yet named) narrator of Archipelago, a translator who, as the novel progresses, seems to allow her own self to be written, to be translated.

Archipelago is a heady read, deceptively quiet and yet rife with private risk-taking and minute transgressions. It’s a novel that sets its own pace and sets its own rules as the narrator, in the process of discovering herself, must also learn how to remember herself.

*

Philip Graham: I have so much to say and ask about this beautifully-written house of mirrors that is Archipelago, your latest novel, that I don’t know where best to start. Perhaps the novel’s own beginning? The narrator, a translator of Greek literature on her way to a literary conference, has a brief but disturbing encounter with an aggressive man. A case of mistaken identity? She has no recollection of this man, but somehow she has become a character in his angry imagination. The possibility of being a “someone else,” seems to cling to her in different ways as the novel progresses.

Meanwhile, she decides to forego reading a novel—titled Occupation—before beginning to translate it, a new professional process for her. “I wanted to try translating something as I was coming to know it,” she says, in order to “tell a story before I knew its ending.” Her translating “blind” sets the stage for another thread in the novel, an acceptance of “unknowing” how her own story will move forward.

As she notes near the end of Archipelago, “the beginning is often many places at once.”

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Joan Silber, in The Art of Time in Fiction, writes: “A story is already over before we hear it. That is how the teller knows what it means.” I really appreciate this sentiment, and I even echo it in the book, but I also think the actual telling of the story helps the teller to understand it, and that each telling, or translation, might privilege different things. I fact, I might say that in Archipelago, her narration is as much the story as any other elements of the work. Read more »

by Daniel Gauss

There are more than 50 armed conflicts going on in the world right now. In fact, depending on how you define “armed conflict,” the number from the most trustworthy sources ranges from around 60 (using a strict, high-intensity definition) to over 150 (using a broader, low-intensity definition). We wake up, take a look at the news and often see that it’s war again. Again. An airstrike, retaliation, another round of funerals and recriminations.

A recent, well-publicized armed conflict was in South-East Asia between a government run by a father/son dictatorship duo and a government still dominated by its military establishment, where generals retain substantial power to influence and often overrule civilian politics at will. Both of these governments demanded and marshalled the patriotic fervor of their respective populations to square off over who “owned” a largely inaccessible 1,000-year-old temple in the middle of a forest, which does not even generate much tourism money. People died.

All these wars, clashes and skirmishes…if you listen closely, really closely, past the rattle of gunfire, the buzz of drones, missiles smashing into concrete buildings, the somber gravitas of the news anchor, you’ll hear it…the soft whimper of a bruised ego.

There is the assumption that war is often rationally motivated. Somewhere in a quiet, high-tech, air-conditioned war room, serious, highly educated and seasoned adults in formal attire or uniforms decorated with medals did the math, weighed strategic interests and analyzed existential threats. We then read that they had no choice but to take action, and, of course, according to the “humanitarian” rules of war, they tried to minimize civilian casualties.

But I sense that beneath all the theatrics is something simpler. Read more »

by Eric Feigenbaum

In 2016, my then-wife and I took our one and three-year-old children from Los Angeles to Bali, Indonesia. It took 21 hours of flight time with one stop in Tokyo to refuel and another in Singapore to change planes – making for a roughly 26-hour journey with two kids in diapers. It is not the easiest way to begin a vacation.

My wife and I were seasoned travelers – both of us having lived abroad before meeting. Asia was no stranger to either of us, and in fact I had lived in both Bali and Singapore in my 20’s. There was a time in both our lives when the best flight was the cheapest one. When flying from Bangkok to Kathmandu for the first time with two buddies aboard Royal Nepal Airlines, we laughed about the used TV cart the flight attendants pushed through the aisle instead of the Boeing-issued ones – purposely included with the plane both for functionality and safety.

One British friend used to take Biman Airlines of Bangladesh back to London from Bangkok, sleeping on the floor of the Dhaka Airport in order to save the most money. Once on a budget flight from Bangkok to Udon Thani, there was so little leg room, I couldn’t sit forward and had to pivot to fit into the row.

It didn’t matter – it was part of the adventure and made for great stories.

Traveling with a one and three-year old across the world was an adventure in and of itself – and suddenly inconveniences were enemies and comforts our best friends. We needed any and every advantage we could get. It became clear to my wife and I that we had reached the age where reducing friction was worth a premium. We needed to rely on everything we couldn’t control going right.

After all, when something goes right, we often don’t notice or comment – but when it goes wrong, it becomes clear that “nothing” is really the hallmark of incredible accomplishment.

This is the bedrock success of Singapore Airlines. Read more »

by Rafaël Newman

At the University of Toronto one winter term in the mid-1980s I took an undergraduate course on classical philology. The instructor was Hugh Mason, a British-born Marxist who once reproved me for wearing a white dress shirt to give a presentation, something he maintained “only a fascist” would have done in his day. (My own politico-sartorial instructions, meanwhile, were issued by The Clash, who cautioned strongly against a wardrobe featuring the colors blue and brown unless one were already “working for the clampdown”). The course was spent for the most part learning about celebrated pioneers of the study of Greek and Latin—among them Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, better known beyond the world of classical antiquity for his dispute with Nietzsche—; but there was also a unit on something called Proto-Indo-European.

PIE, as it is commonly abbreviated, is the hypothetical “mother” of the large, widespread family of tongues comprising Greek, Latin, English, French, and German, but also Russian, Farsi, Lithuanian, Albanian, and Hindi, among many others. Their linguistic ancestor can only be theorized, following the discoveries of British colonial philologists in 18th-century India who compared Sanskrit with Ancient Greek: because there are no written records of languages spoken longer ago than a few millennia.

A putative PIE vocabulary, we learned from Professor Mason, must thus be reconstructed by surveying the modern languages identified as cognate descendants of the earlier idiom for similarly sounding words with related meanings—such as, famously, μήτηρ/mater/mère/Mutter/mother—and using established laws of phonetic evolution to reverse-engineer as their forebear *méh₂tēr (the subscript stands for a particular quality of aspirate, while the asterisk indicates that the word is hypothetical). The PIE reconstruction I recall best from the course, however, and which had no doubt been chosen (or perhaps invented) to reflect the climatic conditions in which we were gathering, in Toronto in February, was *sneghweti: “It is snowing”.

The study of Proto-Indo-European has developed considerably over the past 40 years, since I was first introduced to the idea that winter day in Toronto, its evolution driven by significant technological advances, particularly in the fields of archeology and genetics. In Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global, Laura Spinney gives an absorbing account of the latest attempts to identify and trace the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Spinney, a science journalist, surveys archaeologists, geneticists, and linguists who are reconstructing not only the way those prehistoric peoples spoke, but also how they lived. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The poor and exploited have always had the narrative used against them. The narrative defines them as inferior in some way, and thus deserving of their poverty and exploitation. In ancient times, they were conscripted by the Gods to serve the will of the Gods’ descendant, favored, and prophets. The poor serving the wealthy and/or powerful was the will of the Gods or God, and could extend into the afterlife. In modern capitalist societies, the narrative promotes a fantasy of the non-meritorious. You are poor and/or exploited because you are inferior. You are uncivilized, uneducated, stupid, or lazy. These narratives cast poverty and/or exploitation as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The middle class cannot use the narrative to their advantage to the degree that the wealthy and powerful do. The middle class can only use the narrative to modestly justify its modest advantages. The narrative does not demonize the middle class the way it does the poor and exploited. It does not cast them as savages, morons, or parasites. Instead, it frames the middle class as the laudable backbone of the nation, casting a moral sheen over them. This is consolation for the narrative subjecting the middle class to a volatile message of fear and hope. If you work really hard, and get a little lucky, maybe you’ll become wealthy. But never forget: while things are good enough for now, they are not great, and if you fuck up, you will be punished. For the middle class, the narrative is not just carrots and not just sticks. It is both, carrots and sticks. With a demon authoring half the pages, and an angel authoring the rest, the narrative is a see-saw that repeatedly raises them with promises of a bright future and drops them down to the edge of the precipice, while slathering them with a thin coating of goodness. Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

Standing before Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights in the Prado is an act of surrender. Eyes are consumed by details: naked bodies cavorting in crystalline ponds, human-sized strawberries and a multitude of dripping cherries. There are birds devouring humans, whilst cities are collapsing into flames at the far edge of vision. Each figure is rendered with miniature precision, yet together they overwhelm, producing an excess that resists containment.

Bosch offers no single story; the painting’s power lies in its refusal to be reduced. It is “too much”—and therein lies its meaning. I was not surprised, therefore, to find details from the painting on the cover of Becca Rothfeld’s 2024 book All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess. I had heard so much about this book before finally picking up a copy. Offering a strong critique of our contemporary aesthetics of minimalism, I thought it was a perfect book to pack for my summer of writing. First, working on a novel manuscript at two writers’ residencies, one in Vermont and the next in Virginia, I then made my way to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and then to Bread Loaf. It was two-and-a-half months living out of a small suitcase with that one book along for the ride– in hardcover, of course.

From Marie Kondo’s call for us to “take out the trash” –where trash is defined as anything we are not currently using and enjoying– to the multi-million-dollar mindfulness industry, which similarly sells ways for us to de-clutter, Rothfeld’s book asks us to consider that less is not always more.

Sure, sometimes it is.

Especially for Americans whose lives do so often seem to be spinning out of control, not least of all because of all the stuff we endlessly buy and throw away, by all the choices we have, and how these endless choices seem to define who we are. Maybe for people constantly loading up at Costco and traveling overseas several times a year, with households with so many moving parts, a car per person, Kondo’s style of clean consumerism can feel like a relief, of sorts. I get it. Read more »

When ChatGPT was released late in November of 2022 my immediate response was, “meh.” But then I decided that I needed to check it out, if only out of curiosity. Within an hour or so my reaction went from “meh” to “hot damn!” I put it through its paces in various small ways before deciding to give it a whirl on a task I understood well, interpreting a text. In this case I chose a film, Steven Spielberg’s Jaws. I published the result here in 3QD: Conversing with ChatGPT about Jaws, Mimetic Desire, and Sacrifice (Dec. 5, 2022).

I then dove in with both feet. For about a year or so I was mostly interested in observing ChatGPT’s behavior. In time I began using it as an assistant in my own work, even as a collaborator. I started working with Anthropic’s Claude in November of 2024. Starting in December I did a series of posts in which I had Claude discuss photos I uploaded. At the same time integrating it into my general intellectual workflow along with ChaGPT.

In March of this year I began working on a somewhat speculative book on the long-term prospects of AI. Current working title: Play: How to Stay Human in the AI Revolution. I have been making extensive use of both Claude and ChatGPT in developing the book. I’ve used them for general research, for summarizing some of my scholarly research and evaluating it for use in the book, for working on the overall structure of the book, and more generally for things and stuff. The purpose of this article is to give you a glimpse into that work.

First comes three sections of preliminary materials. The fourth section is a short essay that ChatGPT wrote: Beyond the Human/AI Divide. I conclude with some questions about just who or what wrote that essay.

by Mark R. DeLong

Avital Meshi says, “I don’t want to use it, I want to be it” “It” is generative AI, and Meshi is a performance artist and a PhD student at the University of California, Davis. In today’s fraught and conflicted world of artificial intelligence with its loud corporate hype and much anxious skepticism among onlookers, she’s a sojourner whose dived deeply and personally into the mess of generative AI. She’s attached ChatGPT to her arm and lets it speak through the Airpod in her left ear. She admits that she’s a “cyborg.”

Meshi visited Duke University in early September to perform “GPT-Me.” I took part in one of her performances and had dinner with her and a handful of faculty members from departments in art and engineering. Two performances made very long days for her—the one I attended was scheduled from noon to 8:00 pm. Participants came and went as they wished; I stayed about an hour. For the performances, which she has done several times, Meshi invites participants to talk with her “self” sans GPT or with her GPT-connected “self”; participants can choose to talk about anything they wish. When she adopts her GPT-Me self, she gives voice to the AI. “In essence, I speak GPT,” she said. “Rather than speaking what spontaneously comes to my mind, I say what GPT whispers to me. I become GPT’s body, and my intelligence becomes artificial.”

In effect, Meshi serves as a medium, and the performance itself resembles a séance—a likeness that she particularly emphasized in a “durational performance” at CURRENTS 2025 Art & Technology Festival in Santa Fe earlier this year. Read more »

by Charles Siegel

In the first part of this depressing column, I looked at Congress’ spineless surrender of its power to Trump’s turbocharged executive. In the second part, I tried to set out how that same executive has waged war on the judicial branch, and has rapidly transformed the Department of Justice into its private law firm. Perhaps most disheartening in this sorry saga, however, is how obliging the Supreme Court has been in the steady weakening of the “third branch.” Our highest court — the ultimate symbol of the judicial branch and the temple of its authority — seems perfectly content to let Trump steadily erode its power. In some ways, the Court is actively complicit in Trump’s war.

In the first part of this depressing column, I looked at Congress’ spineless surrender of its power to Trump’s turbocharged executive. In the second part, I tried to set out how that same executive has waged war on the judicial branch, and has rapidly transformed the Department of Justice into its private law firm. Perhaps most disheartening in this sorry saga, however, is how obliging the Supreme Court has been in the steady weakening of the “third branch.” Our highest court — the ultimate symbol of the judicial branch and the temple of its authority — seems perfectly content to let Trump steadily erode its power. In some ways, the Court is actively complicit in Trump’s war.

It is hard to comprehend that we are less than eight months into this administration, such has been the sheer ferocity and speed of Trump’s actions. Blizzards of executive orders, arbitrary firings, wholesale liquidations of entire agencies, mass deportations, ICE abductions, the military in our streets. All of this has resulted in hundreds of lawsuits, many of which (perhaps even most) are seeking relief on an emergency basis. The lower courts have done their level best to deal with the onslaught. But when cases have come to SCOTUS, as inevitably some would, the Court has acted in singularly unhelpful ways.

The Court has sided with Trump and his Department of Justice — and yes, that’s the only way DOJ can be described these days – in the vast majority of cases. The only issue of any importance on which Trump has lost has been the due process rights of persons detained under the Alien Enemies Act, who are about to be deported. There, the Court ruled that they are entitled to “notice …within a reasonable time and in such a manner as will allow them to actually seek habeas relief.” Even then, this decision was enormously helpful to Trump’s agenda, as discussed below. Beyond that, the Court has largely deferred to the executive. Read more »

At the Franz Josef Strauss International Airport in Munich.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Sherman J. Clark

In a recent essay, Don’t Be Cruel, I argued that looking away from cruelty—mass incarceration was my example—comes at a cost. The blindness and mental blurriness we cultivate to avoid discomfort also stunts us. Avoidance may feel like self-protection, but it leaves us less able to flourish. It is hard to find our way in the world when we are self-blinded. Facing hard truths, including cruelties in which we are indirectly complicit, can be a form of ethical weight training—bringing not just sight and insight but ethical strength.

In a recent essay, Don’t Be Cruel, I argued that looking away from cruelty—mass incarceration was my example—comes at a cost. The blindness and mental blurriness we cultivate to avoid discomfort also stunts us. Avoidance may feel like self-protection, but it leaves us less able to flourish. It is hard to find our way in the world when we are self-blinded. Facing hard truths, including cruelties in which we are indirectly complicit, can be a form of ethical weight training—bringing not just sight and insight but ethical strength.

But facing the truth is easier said than done. Because the truth is that our world is rife with horrors: war, injustice, exploitation, racism, rape. Not to mention the corruption, cruelty, and would-be fascism looming in our national life. To confront all this at once would crush us. We recoil not because we are heartless but because we know that knowing more will hurt. Psychologists describe what happens when we don’t avert our eyes. Studies of “compassion fatigue” show how repeated exposure to others’ pain can leave us depleted, even disoriented. Healthcare workers, legal advocates, teachers—those who must confront suffering daily—describe the exhaustion that follows. The problem is not lack of care but its weight: to feel too much, too often, wears down our capacity to respond. We simply cannot see all of it all the time.

Yet this necessity does not remove the cost. The very act of triage—choosing what to attend to and what to ignore—shapes us. We become people who can bear certain kinds of truth and not others. Sometimes that protective instinct is wise; no one can survive without rest. But sometimes it dulls into habit, and habit into incapacity. We find ourselves avoiding not just unbearable horrors but also discomforts we might well endure—and from which we might grow. We are caught in a bind. On one side: cultivated ignorance that seems to let us glide through life but costs us our growth. On the other: overload, the crushing weight of truths too terrible to bear. How do we remain open to what we must know without being undone by what we see?

The difficulty is not only volume. Certain kinds of knowing carry their own dangers. True knowing requires not just information but empathy. Facing cruelty in a way that conduces to ethical growth means not just memorizing incarceration statistics but recognizing human suffering. And that kind of knowing destabilizes us in subtle ways.

To enter another’s world is to blur the edges of our own. Psychologists call this “self-other overlap”: the merging of boundaries when we take another’s perspective seriously. Sometimes this deepens connection; but it can leave us disoriented. Empathy can also distort. We feel more readily for those who are near, familiar, or attractive. One vivid case moves us more than anonymous thousands. This is not a flaw in our compassion so much as a feature of it—but it means empathy, untethered, can mislead. We may confuse emotional resonance with clarity, or feel righteous for “feeling the pain” without addressing its source.

So the problem is not just quantity but quality. Some ways of knowing, even in small doses, can unsettle us or send us astray. Empathy is indispensable to our humanity, but it is also risky. We need not only courage to face what is hard to know, but discernment about how we face it. Read more »

Secrecy has long been understood as a danger to democracy—and as antithetical to science. But how much of scientific knowledge is already hidden?

by David Kordahl

“Our society is sequestering knowledge more extensively, rapidly, and thoroughly than any before it in history,” writes physics Nobelist Robert Laughlin in his opinionated 2008 tract The Crime of Reason: And the Closing of the Scientific Mind. “Indeed, the Information Age should probably be called the Age of Amnesia because it has meant, in practice, a steep decline in public accessibility of important information.”

Before reading Laughlin’s book, I had not been aware of Howard Morland, whose 1979 article “The H-Bomb Secret” provides a dramatic case in point. The article begins directly: “What you are about to learn is a secret—a secret that the United States and four other nations, the makers of hydrogen weapons, have gone to extraordinary lengths to protect.” The next sentence reveals why the U.S. government sought an injunction to halt publication. “The secret is in the coupling mechanism that enables an ordinary fission bomb—the kind that destroyed Hiroshima—to trigger the far deadlier energy of hydrogen fusion.”

“The H-Bomb Secret” can be easily accessed on the Internet. It contains information about the Teller-Ulam design that remains classified to this day, and was written as an explicit challenge to the regime ushered in by the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, which decreed nuclear knowledge to be “born secret,” automatically restricted by virtue of its subject matter. Morland’s article presented an edge case, since its sources were public, ranging from encyclopedias to government press releases. United States vs. Progressive, Inc., the suit to stop its publication, was eventually dropped. In pretrial hearings, government lawyers accidentally revealed additional details about the bomb. In a comedy of errors, other activists were drawn to the cause, which ultimately led government litigators to dismiss their own case.

United States vs. Progressive, Inc. is celebrated as a test of the limits of the First Amendment, but it also serves as a parable about scientific secrecy. Howard Morland was not himself a scientist (his science training consisted of five undergraduate elective courses), but his article contains more concrete information about how H-bombs work than anything I learned while getting a doctorate in physics (and, yes, I did once take a nuclear physics course).

The larger question in play here is that of how much scientific knowledge is freely available, vs. how much powerful actors have been able to deliberately obscure. Read more »

by Marie Snyder

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book, Losing Ourselves: Learning to Live Without a Self.

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book, Losing Ourselves: Learning to Live Without a Self.

Garfield traces arguments against the existence of a self primarily through 7th century Indian Buddhist scholar Candrakīrti and 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume, and explores where many other philosophers hit or miss the mark along the way. The book is a surprisingly accessible read about a complex topic with perhaps the exception of a couple more in-depth chapters that develop arguments to further his conclusion: you don’t have a self, and that’s a good thing.

Garfield starts with the idea of self from ancient India: the ātman is at the core of being. A distinct self feels necessary to understand our continuity of consciousness over time (diachronic identity) and our sense of identity at a single time (synchronic identity). A self gives us a way to explain our memory and allows for a sense of just retribution when we’re wronged. We feel a unity of self to the extent that it’s hard to imagine it’s not so.

However, Garfield argues that feeling of having some manner of core self is an illusory cognitive construction. Hume claimed the idea isn’t merely false but gibberish, and Garfield calls it a “pernicious and incoherent delusion.” We cannot infer from a sense of self that there is a reality of self. Garfield asserts that, “We are nothing more than bundles of psychophysical processes–changing from moment to moment–who imagine ourselves to be more than that.” We are similar to the person we were yesterday and a decade ago because we’re causally related yet distinct. We share enough properties and social roles with ourselves to feel as if we’re the same over the years. That causal connectedness enables the memory of the past and anticipation of the future. Read more »