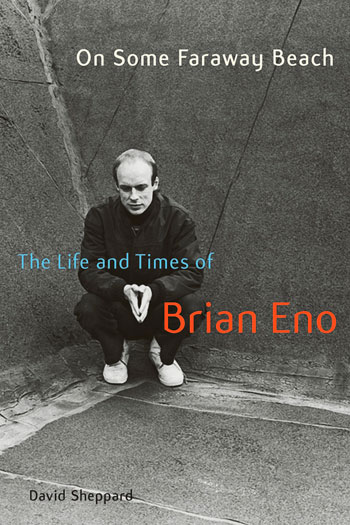

David Sheppard is the author of On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno, the first and only biography of rock music's foremost intellectual “non-musician,” producer and cultural theorist. The book covers Eno's early life growing up in England listening to early soul records, his formative period in art school, his entrance into the public eye as the synthesizer player with Roxy Music and his career's subsequent fragmentation across the cultural landscape, into the realms of visual art, ambient music, record production (for the likes of U2, David Bowie, Talking Heads and Coldplay), writing and futurology. Colin Marshall originally conducted this conversation on the public radio program and podcast The Marketplace of Ideas. [MP3] [iTunes link]

This is a question coming from one Brian Fan to another, and it's one I've always had difficulty with: what is the concise answer that you give — say, when you were working on the book and they asked you want it was about and they didn't know who Brian Eno was, so they asked “Who's Brian Eno?”, what did you say?

This is a question coming from one Brian Fan to another, and it's one I've always had difficulty with: what is the concise answer that you give — say, when you were working on the book and they asked you want it was about and they didn't know who Brian Eno was, so they asked “Who's Brian Eno?”, what did you say?

I've yet to come up with the pat sentence that actually answers that, as indeed has Brian. I mention in the intro to the book that he got so fed up with trying to answer that question at dinner parties, explaining this enormously complex dilettante artist, cultural theorist, etc., etc. job description that he instead just said he was an accountant, which made people go away very, very quickly.

How did your own history with the enjoyment of Brian Eno's work begin? What was your introduction to him?

I came across him as a sort of callow youth, listening to punk rock records. He got all the mentions in the margins. I was aware of him in Roxy Music, but I was a bit too young for that, so it was a kind of ethereal presence initially. He got mentioned in dispatches by all sorts of people in punk rock. When I first got to hear his music, which in any serious capacity would have been about '78, what I heard sounded nothing like what I expected. I expected something far more severe and metallic.

Obviously I knew things like Low, the David Bowie record he'd worked on, and I'd never really associated his involvement in those records with the more calm and ethereal elements. Somehow I imagined him to be more Velvet Underground and less lift music — to be honest, when I first heard ambient music I, like many others, didn't fall immediately in love with it. I did think it was rather bland.

My initial reaction to Brian Eno was one of disappointment — one which quickly turned around. Something happened very shortly after that. I think it was just part of my growing up, actually. A light went on somehow, and it all suddenly made enormous sense. The more I investigated it, the more sense it made.

You mention this intro was in the late seventies, when Brian was in the process of inventing and releasing the first ambient albums. For those in the audience who might not know, how did Brian enter the public eye? What things was he first famous for?

His introduction to the masses would have been through playing synthesizers with Roxy Music, certainly in the U.K. This was this very strange pop group, even for a time of very strange pop groups. Bryan Ferry was the lead singer and Brian Eno was this guy, a self-confessed non-musician, who played synthesizers and actually played a lot of the instruments in the band, more traditional, guitars and so forth, and filtered them through his electronic effects. This was a revolutionary thing to be seen in pop music in 1972, which is when they struck. They went swiftly to the top of the British charts. I think they took a bit longer to penetrate America.

That would've been Eno's calling card to the world, but he was only actually with Roxy Music for two albums. By 1973, he was off on his own. He'd fallen out with Brian Eno — with, uh, Bryan Ferry, rather, the singer. Probably less confusing with two Brians in the band, for one thing, but they had a conflict of interest over where the band was going. Bryan Ferry, I think, was always looking to be a more orthodox pop star, and was moving in that direction. Eno comes from an art school background, and wanted to pursue music that reflected that more. Ultimately, that's when he struck out on his own. But it would've been Roxy Music that first awakened the world to Brian Eno.

Read more »