by Rebecca Baumgartner

The short stories in Kindergeschichten (Children’s Stories, 1969) by Swiss author Peter Bichsel are not actually for children. True, they are short, easy to read, and feel a bit like spare, minimalist fairy tales. But the moment you think you’ve grasped what they’re all about, they slip away. In the introduction to my German language edition, the stories are said to “seduce us, playfully, into thinking,”* and this was exactly my experience reading them. It’s not that they’re inappropriate for children, but more that children will likely only find them silly, whereas an adult will very likely see layers of meaning and existential crisis.

Some of the stories are about a person who takes an absurdly skeptical stance about something that is widely known. For example, in the story “Die Erde ist rund” (“The Earth is Round”), the protagonist knows intellectually that the Earth is round, but he doesn’t truly believe it, so he undertakes an absurd journey to prove it to himself.

The stories also feature characters who ridiculously imagine that they can live outside the confines of society and pursue radical autonomy. For instance, the protagonist of “Ein Tisch ist ein Tisch” (“A Table is a Table”), having grown bored with his humdrum life and grown frustrated with how things always stay the same, decides to give different names to everyday objects, with the result that no one can understand him when he speaks. He ends up forgetting the original names for things and eventually falls silent, able to talk only to himself.

The ideal of radical autonomy, or life outside a community of knowledge, is the theme of another story, “Der Mann, der nichts mehr wissen wollte” (“The Man Who Didn’t Want to Know Anything Else”). The titular man decides to enclose himself in a dark room so that he won’t have to know what the weather is like outside. But when he realizes that he still knows about the mere existence of good and bad weather, he finds this knowledge intolerable. He comes to the conclusion that the only surefire way to be sure he won’t learn anything more is to learn everything first, and then reject it. “I must first know what I don’t want to know!” he cries, before proceeding to teach himself Chinese.

Bichsel hints that these absurdities are the natural result when a person removes themselves from their community and its communal knowledge. These characters lack “common sense,” the sense jointly created by the commons. But what’s also interesting about these characters is that their extreme individualism, their dedication to their ideals, and their confidence in their own certainties, initially pursued as solutions to their boredom or frustration, don’t end up making them happy.

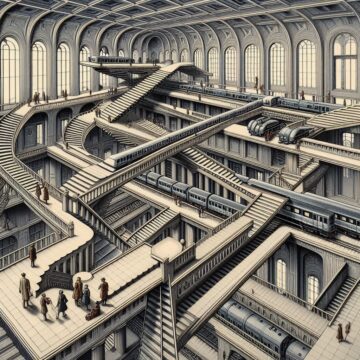

For example, the story “Der Mann mit dem Gedächtnis” (“The Man with the Memory”) features a man who has memorized the timetables of his local train system, but has never been on a train himself. He feels there is no need to actually ride one, since he knows where each one will end up and at what time, and he fails to appreciate that people use trains as a means to get somewhere else. He has abstracted his knowledge from reality in the most nonsensical way. When he notices that the same people leave the station in the morning just to return again in the evening, day after day, he flies into a rage of self-satisfied contempt and tries to (in his mind) ruin the passengers’ fun by maliciously telling them where their train will take them and when they will arrive, as though spoiling the plot of a movie.

But when an information desk opens in the train station, the man questions the official at the desk and realizes that someone else has access to the same knowledge he does. He’s not special anymore. In a fit of pique, he burns all his timetables and decides to give up his obsession. The next day, however, he decides to ask the official at the information desk something else entirely. “How many steps does the staircase outside the station have?” he asks. When the official responds, “I don’t know,” the man with the memory is so overjoyed to know something the official doesn’t that he proceeds to count all the steps in the city and eventually all the steps in the world. The story ends by saying that he did this “in order to know something that no one else knows and what no official can learn from a book.” One still gets the sense, though, that he doesn’t quite know what trains are for.

Perhaps the most tragic story in the collection is “Der Erfinder” (“The Inventor”). The main character, an inventor, is a recluse by choice. He stays holed up in his home, far from the city and cut off from all outside news because, he insists, inventors need peace and quiet to come up with their inventions. He works day and night, and never finds anyone who understands him or his work, so he decides there’s no point in communicating with other people. In the rare event he gets a visitor, he hides his work from them, fearful that his visitor will steal his ideas or laugh at him. He does this for 40 years.

Eventually, he has a breakthrough: he has finally invented something. He decides to go into the city and tell people about it. Not surprisingly to the reader, the city he knew has changed drastically in 40 years. New technologies are everywhere. Because the inventor is smart, he instantly grasps what each new technology is for and how it works. When he first sees a traffic signal, he duly obeys the red and green lights.

As he continues exploring the city, though, whenever he marches up to strangers and abruptly tells them he’s invented something, people’s responses are far from gratifying: some ignore him, some laugh at him, nearly all of them think he’s a weirdo. His self-centeredness and years of social isolation are to blame for this. He has forgotten the purpose of small talk and, ironically, his years spent inventing have robbed him of all curiosity about other people and what they need. “Because the inventor hadn’t spoken to people in a long time,” the narrator says, “he didn’t know how to start a conversation anymore.”

It comes out that what’s he’s invented is essentially a television, which of course already exists. A kindly soul takes pity on him and explains the situation, and asks if the inventor would like him to demonstrate how a TV works. “No,” the inventor says. “I’d rather not see it.” When faced with the tangible realization of his life’s work, he has no desire to see it in action, simply out of spite for not having been the first to invent it – a depressingly human way to respond.

At this point, crushed by disappointment, the inventor no longer pays heed to the traffic lights – symbolically removing himself even further from the social contract. He goes home and proceeds to re-invent everything he saw in the city, sketching out designs and calculations for refrigerators, cars, escalators, telephones. Upon finishing each design, he trashes it and says despairingly, “This already exists.”

***

These stories are so light on detail and so short that they appear deceptively simple, something winked at in the title of the book. But a moment’s reflection leaves the reader to follow all kinds of disconcerting paths and possibilities. For each reader these thoughts will be different, of course, based on their own life and their own concerns. That’s the beauty of fables, fairy tales, and other seemingly simple stories, which present scenarios so outside of normal experience that the universality of their themes shines through, inviting each reader to build their own meaning from the bare bones of the story.

For me, because of the stage of life I’m in and the concerns I’ve been facing lately, Bichsel’s stories bring to mind thoughts about workaholism and our drive to keep busy – busy doing anything other than questioning our need to keep busy. These stories gently pinch us awake; they confirm our suspicion that maybe, sometimes, we’re working hard for no purpose, and distancing ourselves from other people in the process. How much of what we do in our jobs is the equivalent of counting steps because an executive decided that knowing the quantity of steps in the city (so to speak) is now a strategic priority? How much of our ambition is a pointless competition that doesn’t accomplish anything or make us any happier?

As much as we can clearly see how laughable these characters are, the stories don’t flatter us into thinking we’re any different; they tell us bluntly that sometimes our ideals of self-sufficiency and autonomy are a bit ridiculous. They remind us that if we won’t admit we need other people, we will become simply a more outwardly put-together version of the man shouting in a train station or the man who calls tables rugs and ends up muttering to himself because no one can understand him. We become the man who is so humiliated by not being as special as he thought he was that he’s no longer interested in anything he can’t personally take credit for.

The stories in Kindergeschichten are also brutally honest about our tendency toward wishful thinking. The world has a reality of its own, and when we enclose ourselves away from it, or deny it, or ignore it, or attempt to break from it, the results are not heroic – they are pathetic. But, note that steering clear of wishful thinking doesn’t mean avoiding imagination or creativity. Quite the opposite. Only by fully participating in the world as it really is can someone imagine and create what the world needs. The usefulness of reality is that it confines our energies to what matters.

This unsentimental approach to imagination is emphasized in the introduction to Bichsel’s collection, which says that the stories are for “readers who haven’t stopped asking ‘What if?’” What if we didn’t take ourselves so seriously or hold our ideals so tightly? What if we listened more to the people around us, the conscience of the community? What if we took action to bring real change into our lives rather than simply calling the same situation by a new name? What if we dropped the ideal of the rugged individualist, the awe towards entrepreneurism, and embraced the inheritance of what other people have already made? What if, as an antidote to isolation and despair, we enjoyed the rich abundance of the world as it already is, which includes valuing the things that weren’t created by just one person – our languages, cultures, philosophical traditions, systems of artistic influence, and accumulated expertise?

The antidote to wishful thinking and the way to avoid becoming any of these absurd, pathetic characters is easier said than done. We have to trust systems of expertise so as not to fall down rabbit-holes of ridiculous skepticism. We have to remain a part of the community that we live in so that we can understand others and be understandable to them. We have to be careful that our energies and talents are being used in a way that will help us and the world around us, rather than simply filling up time or gratifying our egos; we must ensure our lives don’t turn into busywork.

Most importantly, we must remain curious and open to the experiences of other people, as a counterweight and corrective to our own self-absorption. It’s by connecting with others and muting the background noise of our own private worlds that we can be seduced, playfully, into thinking.

*All translations from the original German and any resulting errors are my own.