by Claire Chambers

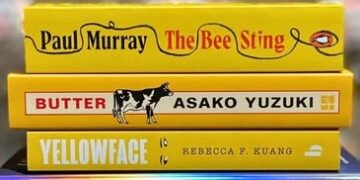

Recently I’ve noticed that a new wave of state-of-the-nation – or, more accurately, ‘state‑of‑the‑world’ – novels tend to arrive clad in yellow dust jackets while bearing short, even one‑word, titles. I’m thinking of books like Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting, Asako Yuzuki’s Butter, and Rebecca F. Kuang’s Yellowface. Published in English within a year of each other, in 2023–2024, perhaps their look comes from the fashion moment yellow is having. Although the trending shade is a softer, creamier hue than the bright pop of the novels’ daffodil covers, the books’ appearance is on point for this moment in the mid-2020s. This cheerful styling helps make bookshops’ cash registers sing, appropriately enough, like canaries. In a not dissimilar way to Tadej Pogačar, who has just won the Tour de France in his yellow jersey, these books are some of the leading literary winners of the past half decade.

Recently I’ve noticed that a new wave of state-of-the-nation – or, more accurately, ‘state‑of‑the‑world’ – novels tend to arrive clad in yellow dust jackets while bearing short, even one‑word, titles. I’m thinking of books like Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting, Asako Yuzuki’s Butter, and Rebecca F. Kuang’s Yellowface. Published in English within a year of each other, in 2023–2024, perhaps their look comes from the fashion moment yellow is having. Although the trending shade is a softer, creamier hue than the bright pop of the novels’ daffodil covers, the books’ appearance is on point for this moment in the mid-2020s. This cheerful styling helps make bookshops’ cash registers sing, appropriately enough, like canaries. In a not dissimilar way to Tadej Pogačar, who has just won the Tour de France in his yellow jersey, these books are some of the leading literary winners of the past half decade.

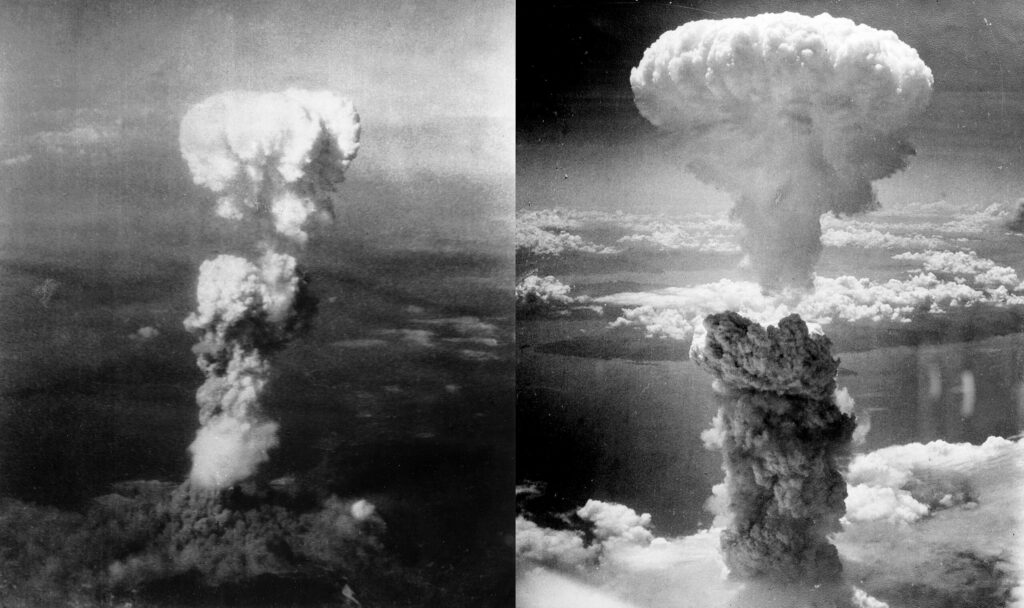

More significantly, this branding evokes both the social menace of the yellowjacket wasp and the macabre suspense of the TV thriller with the same waspish name. Such books carry the visual sting of a cautionary tale, even though the trio of novels are also often very funny. Their spines flash like hazard tape or symbols for radioactive waste and chemical toxins. The promise, or threat, is for narratives smarting with ecological or technological dread and familial devastation. Texts like The Bee Sting, Butter, and Yellowface are comic, edgy, and hyper-current. The literary exemplars tacitly, and probably unconsciously, recall the work of Jordan Peele. This African American film director makes movies about social division with one- or two-word titles: Get Out (2017), Us (2019), and Nope (2022). The novels, meanwhile, articulate our collective anxiety about global warming, gender and race relations, and a loss of trust in originality, truth, leaders, and institutions. In the terse titles The Bee Sting, Butter, and Yellowface the world feels compressed into a single, loaded word or phrase. The yellow jacket motif unites them: colourful and alluring on the shelf, yet signalling danger and the risk of a lethal heartbeat. Across these novels, the unmooring of climate time intersects with fractured family chronologies, as personal histories accumulate like toxic detritus. Read more »

There was a prevailing idea, George Orwell wrote in a 1946 essay

There was a prevailing idea, George Orwell wrote in a 1946 essay

Rania Matar. Samira, Jnah, Beirut, Lebanon, 2021.

Rania Matar. Samira, Jnah, Beirut, Lebanon, 2021.

A South Asian person I dated for a year complained to me one day that I was too Iranian. He said a lot of things I did had that tint and flavor to them. We were eating lunch that I had prepared, which consisted of rice and chicken, and I had a plate of fresh herbs that accompanies most meals in Iran. As he was enjoying his meal, he continued that he had never met someone as still ingrained in their own culture as I was. When I pressed for details, he said things like having pistachios and sweets at home to go with tea, or serving fruit for dessert. The irony of it all is that he loved it when I cooked Persian dishes and enjoyed them when I sent him home with leftovers, and really appreciated the snacks I had in my house to accompany his 5 pm scotch.

A South Asian person I dated for a year complained to me one day that I was too Iranian. He said a lot of things I did had that tint and flavor to them. We were eating lunch that I had prepared, which consisted of rice and chicken, and I had a plate of fresh herbs that accompanies most meals in Iran. As he was enjoying his meal, he continued that he had never met someone as still ingrained in their own culture as I was. When I pressed for details, he said things like having pistachios and sweets at home to go with tea, or serving fruit for dessert. The irony of it all is that he loved it when I cooked Persian dishes and enjoyed them when I sent him home with leftovers, and really appreciated the snacks I had in my house to accompany his 5 pm scotch.