by David Kordahl

Peter Morgan has worked for decades to appreciate the underlying structures of physics. But can he convince others he is right?

When I receive unsolicited scientific communication, I bin writers into two crude categories: Possible Collaborators, and Probable Crackpots. Of course, these categories may overlap. Ted Kaczynski, after all, taught at Berkeley before he made those bombs.

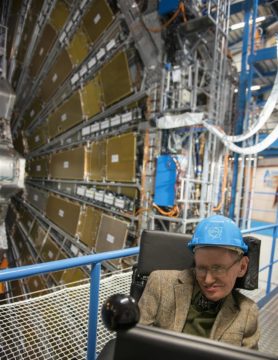

When I first received a message from Peter Morgan, I wasn’t sure where to slot him. The fact that he was listed as a lab associate for the Yale University Physics Department pushed the needle of my prior judgment toward Collaborator. But the fact that he was cultivating journalists to promote his ideas about quantum theory…well, that swung my needle far the other way.

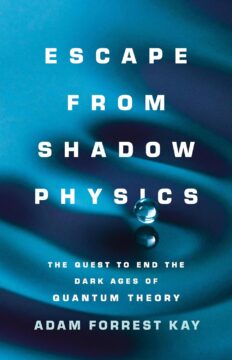

Morgan first contacted me on X.com (the website formerly known as Twitter) on December 9, 2024. I had posted the review of Escape From Shadow Physics: The Quest to End the Dark Ages of Quantum Theory that I had written for 3 Quarks Daily, and he posted a short comment in response. Seeing Morgan’s frequent physics posts, I followed him. Minutes later, he pitched me a column idea.

Morgan suggested that I write about his ideas:

I hope that if there are any of the ideas that deserve to go viral, they will do so sooner rather than later, then I can admire what better mathematicians and physicists than I am can do with whatever survives the winnowing. There are quite a few people who react positively to how different this is (for one thing it’s not a ToE, and the data and signal analysis aspect is met almost joyfully by some people), but I’m so far out in left field that nobody quite believes that I’m not making some obvious mistake. It’s always embarrassing to be the person who champions nonsense, right?

Right. I went to Morgan’s profile and watched one of the talks on his YouTube channel. After realizing I had no immediate way of assessing whether there was any there there, I sent him a polite but noncommittal reply, and placed a mental bookmark, thinking I might contact him again once I had time to spare. Read more »

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “