by Laurie Sheck

1.

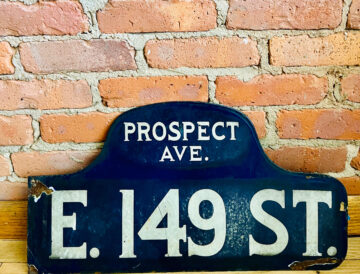

In the summer of 1977 in New York City—summer of the famous city-wide blackout, its fires and looting—my parents stole a street sign. The sign marked the location of my father’s housewares store which overnight had been turned into a hollow shell of blackened ash and charred brick. Looted and burned.

The sign was a remembrance of a place they had loved.

The store was in the South Bronx, which at that time was the highest crime district of NYC. 149 St. and Prospect Ave. From earliest childhood, I spent many hours there dusting shelves, sticking price tags onto merchandise, and performing a variety of other minor tasks. The store and the neighborhood were a large part of my childhood world, of my introduction to what a world even is. My father and his older brother left school in the 9th and 10th grades to support their family. His brother had died young. Now, with the blackout of July 13, overnight the neighborhood was decimated. The store was gone.

2.

Even before the blackout, the South Bronx was notorious for its empty lots and abandoned buildings, its street gangs and drugs. Of course back then, as a child, I was unaware of the statistics. I didn’t know that roughly 20 percent of the buildings stood empty, abandoned by landlords unwilling or unable to maintain them. Unemployment was nearly double the rate of the city as a whole. Fewer than half of heads of households were said to be employed. The median income was $4,600, substantially below the median for the city. One study showed the median household size as 5.0, whereas the median household size for the city overall was 2.2. Families were crowded into tiny spaces. About half of the households were headed by women.

In 1977, the Women’s City Club of New York City issued an extensive report on the area, With Love and Affection: A Study of Building Abandonment. In addition to gathering numerous statistics, the report described the relentless deterioration of the neighborhood dating back to the late 1960’s. The blackout intensified what was already there: “block after block of empty buildings, some open and vandalized, some sealed, standing among rubble-strewn lots on which other buildings have already been demolished. In the midst of this desolation there is an occasional building where people are still trying to live.” It went on, “The streets and sidewalks…are littered with rubbish, with shattered glass out of the gaping doors and windows.” A New York Times article from 1975 bore the headline “To Most Americans, The South Bronx Would be Another Country.”

And yet, even as my memories resonate with much of what the WCC report described, I also remember bustling streets, restaurants, families. Read more »

Philip Graham: The home page of your new and expanded author’s website,

Philip Graham: The home page of your new and expanded author’s website,

The question of the day on everyone’s minds is whether AI is a boom or a bust. But if we lift our eyes ever so slightly from the question of the day and look at the bigger picture, two bigger questions come into view.

The question of the day on everyone’s minds is whether AI is a boom or a bust. But if we lift our eyes ever so slightly from the question of the day and look at the bigger picture, two bigger questions come into view. In Arabic, the word

In Arabic, the word  Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Temple, Jogjakarta, Indonesia, October 2025.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Temple, Jogjakarta, Indonesia, October 2025.

There can have been very few musicians who played such key roles, in so many different bands in so many different genres, as Danny Thompson. When he died at 86 in September, music lost one of its great connectors.

There can have been very few musicians who played such key roles, in so many different bands in so many different genres, as Danny Thompson. When he died at 86 in September, music lost one of its great connectors. Language: Ooh, a talkie!

Language: Ooh, a talkie! There are contradicting views and explanations of what dopamine is and does and how much we can intentionally affect it. However, the commonly heard notions of scrolling for dopamine hits, detoxing from dopamine, dopamine drains, and

There are contradicting views and explanations of what dopamine is and does and how much we can intentionally affect it. However, the commonly heard notions of scrolling for dopamine hits, detoxing from dopamine, dopamine drains, and