by Michael Liss

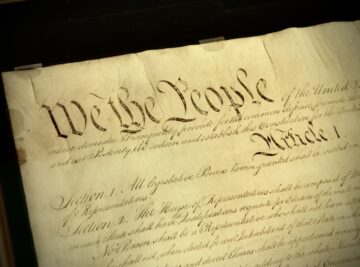

The principles of Jefferson are the definition and axioms of free society…. All honor to Jefferson—to the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and so embalm it there, that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression. —Abraham Lincoln, April 6, 1859 Letter to Henry L. Pierce and others.

An extraordinary man. Two extraordinary men, whose lives were bound together by a common thread of devotion to an idea of self-government in which all men are created equal. It is true that they did not understand it in exactly the same way (you cannot ignore the stain of slavery). Yet, the kind of people who rejected Jefferson’s core concept had—in his time, in Lincoln’s time, and now—a purpose: in Lincoln’s words, “supplanting the principles of free government, and restoring those of classification, caste and legitimacy.”

We are less than two years away from the 250th anniversary of Jefferson’s defining words, and yet it seems we are less certain, less secure, perhaps even less committed to the idea of self-government.

There is a stunning AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll that was just released, which reported the finding that “[o]nly 21% of adults feel U.S democracy is strong enough to prevail no matter who wins the election in November.”

Just exactly what is the “U.S. Democracy” that may not prevail? Before we go further, we ought to get some nomenclature misunderstandings out of the way. Let’s introduce Democracy’s cousin, the “Constitutional Republic.” Yes, we live in a Constitutional Republic and not a Democracy. No, that’s not a concluding and conclusive argument any time someone wants to make government more representative, more answerable to the voters, or less beholden to privilege. Opponents of change who invoke the phrase “mob rule” just highlight the fact that what’s at stake isn’t high principle, but rather a desire to “supplant[] the principles of free government, and restor[e] those of classification, caste and legitimacy.”

There are no “pure democracies,” even if we frame it that way out of convenience. To quote from a 2017 essay by Ryan McMaken, Executive Editor at the (very not liberal) Mises Institute:

[I]f anyone wants to argue against majoritarianism, he should simply do so. There is no need to rely on a half-baked usage of the writings of ‘the Founding Fathers’ who clearly supported a political system in which majority votes play a big part in selecting elected officials, and which is obviously a democracy according to the modern usage of the term.

In actuality, we have always had a constitutional republic, rather than a democracy. That we call it Democracy changes absolutely nothing. It’s the substance of the argument that ought to matter. The Founders did not first put an electric fence of privilege around the Constitution, and then bind for eternity all succeeding generations. Rather, they understood that Madison’s intricate document was imperfect, but it created a mechanism (through Amendment) to update it. It’s not easy to pass an Amendment, but it has been done many times, and in the service of expanding individual liberties and “Democracy.”

Are the barnacle-encrusted impediments to changing the Constitution sometimes too formidable to overcome potential injustice? Perhaps the Founders were unwise when they built in structural barriers to certain kinds of reform. Perhaps they were also a little bit selfish, preserving power where it might have mattered most. In any negotiation, you have to give to get, and the price for those who saw the Articles of Confederation as a high-minded suicide pact was a certain amount of unfairness.

So, when Benjamin Franklin was asked, after the Constitutional Convention, what type of system of government they had created, his answer was: “A republic, if you can keep it.” Left unmentioned in the quote, but clearly inferable from Franklin’s public and private statements was something more. A “republic” doesn’t merely spring from the people’s initial consent. It will die without their active participation. There is a civic duty to inform yourself, to involve yourself, to vote, to use and respect those enumerated rights, and to hold power accountable. Franklin would never have joined the “burn it all down” crowd—the words “if you can keep it” demand that citizens insist on their rights, and in a sustained fashion.

What about Jefferson? So (deliberately) opaque at times, but at a peak of his talents in the Declaration of Independence. When Lincoln seeks inspiration at Gettysburg, it’s Jefferson, not Washington, or Adams, or Madison that he finds. Jefferson says,

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Lincoln, whose poetry is the equal of Jefferson’s, looks past the ratification of the Constitution and the defeat of the British, all the way back to the “proposition” that Jefferson’s draft set forth: a conception of a different kind of nation, based in law, yes, but conceived in liberty and inspired and nourished by the idea of freedom.

Lincoln sees something that Jefferson did—the uncertainty of the proposition, the newness, the radical nature of demanding liberty unfettered by governmental fiat, whether from a monarch or a government. Lincoln seizes on Jefferson’s vision, builds on his platform of a government created by the consent of the governed, and then expands it: “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.” Lincoln’s “new birth of freedom” is a type of codicil meant to expand the number of beneficiaries of Jefferson’s bequest. Lincoln is striving for something beyond what Jefferson did, but he can only reach it by standing on Jefferson’s shoulders.

Before Garry Wills wrote his unsurpassable Lincoln At Gettysburg, he authored Inventing America: Jefferson’s Declaration Of Independence. Inventing America is a very close examination of the text of Jefferson’s original draft and how it was altered (mangled, in Jefferson’s view) by Congress before its adoption. What Wills does is far beyond the scope of this essay, but a couple of his many insights are particularly relevant here.

Jefferson’s original draft used the phrase “inherent and unalienable” rights, but Congress struck “inherent” and changed it to “certain unalienable rights.” There’s a lot packed in there. Both constructions veer off sharply from the classical and medieval thought that the individual was to be governed, and possessed few, if any, individual rights, either certain or inherent. In that time, one could gain rights derivatively through your sovereign or your nation, but none were either inherent or unalienable. From the same sentence, Congress went along with another of Jefferson’s formulations, where he deviated from the Lockean “Life, Liberty, and Property” by substituting, for “Property,” “the pursuit of Happiness.”

These may both be subtleties, and it may be torturing the text, but it seems they have an application that resonated. While “certain” instead of “inherent” appears to be limiting, Wills suggests that Congress had already agreed on a list of rights, and “certain” referred specifically to those. Given the essentialness, 13 years later, of the Bill of Rights to the ratification of the Constitution, this change looks farsighted. As to Locke, Wills points out that Jefferson’s deletion of “Property” might have had its roots in his rejection of old European rights like the entail, which bound property to family for many generations. A new nation, defining an expanded menu of rights, could move to free up property so it could be alienated, thus making more land available for the un-landed classes (presumably to seek happiness).

Why do we care about all of this? To an extent because it relates to a central conflict in our own government: If American Democracy is a system of governance that is also a respecter and protector of rights, exactly what rights are to be respected and protected?

Theoretically, at least, those rights that are stated in the Constitution, inclusive of the Bill of Rights, and any rights-expanding Amendments (like the 13th, 14th, 15th, 17th, 19th, and 26th) that followed. We can add on any rights-expanding, but less secure, newer laws adopted by Congress and signed by the President. As we all know, those rights arising from legislation are subject to repeal or “cancellation” by a disapproving subsequent Congress or Supreme Court.

What is it that we want? Let’s divide up rights into three personal buckets. The first holds the rights we all possess and that also happen to be the ones we personally value. The second holds the rights we all possess, but about which we are personally agnostic. The third holds the rights we all possess, but about which we have strong negative feelings.

A “true” principled small-D democrat respects them all, because that’s what the (amended) Constitution says, and we are a nation of laws, and “this is the deal” that we made, or that was made on our behalf by the Founders.

Our problem right now is a diminishing number of “respect them all” folks out there, particularly among politicians, special interest groups, and the social and traditional media. Our American Democracy survives because a critical mass of voters sees great value in it, but voters don’t do politics 24/7. They have lives to lead, jobs, families. Their exposure to politics is often limited to the outlets of the destructively ambitious and the greedy. Their faith in government cannot help but be eroded.

We must fight against this. Resist the politicians who find that the easy way out is lighting fires and then pouring gasoline over them. Reject the amorality that leads pols to do something clearly wrong for a chance at an open mic and a few bucks. Support good people who wish to participate but fear being doxed or slimed or even being compelled to walk in the swamp. Emphasize to our elected leaders how important impartiality is in the courtroom. Clearly communicate that those of us who “consented to be governed” did so on the condition of receiving, in return, an honorable effort and a commitment to decency.

We are the heirs of Madison’s magnificent and magnificently flawed system. The heirs of Jefferson’s idealism and Lincoln’s dogged quest for justice. We are the ones charged by Franklin to keep our Republic.

What America needs right now, more than anything else, is a healthy dose of civic virtue. If some insanely high number of voters think American Democracy may not be strong enough to prevail, then participating is the only answer.

I’ll leave to Jefferson the last words:

Timid men prefer the calm of despotism to the tempestuous sea of liberty.