by Marie Snyder

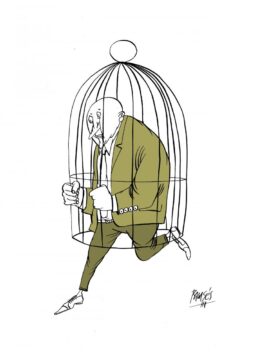

Many of us live in a punitive, carceral type of society that can make it difficult to have compassion for ourselves or others. It’s an era of the glorification of the individual over the group, leading to perfectionism and narcissism and so, so much loneliness. We can’t connect when we’re working with blind determination to find our place above the rest. We can’t connect when we don’t dare show an ounce of vulnerability for fear of being taken down like a wounded gazelle on the Serengeti. Our quest to rise to the top for the security we think comes with status and money is completely at odds with our very real need to feel authentically known, within the security of a community.

Many of us live in a punitive, carceral type of society that can make it difficult to have compassion for ourselves or others. It’s an era of the glorification of the individual over the group, leading to perfectionism and narcissism and so, so much loneliness. We can’t connect when we’re working with blind determination to find our place above the rest. We can’t connect when we don’t dare show an ounce of vulnerability for fear of being taken down like a wounded gazelle on the Serengeti. Our quest to rise to the top for the security we think comes with status and money is completely at odds with our very real need to feel authentically known, within the security of a community.

We’re no longer following that love and forgiveness bit from Christianity, if we ever really did wide-scale. And we project our fear of losing on anyone who has suffered through difficulties, no matter if it’s a natural disaster or massive layoff. We distance ourselves from the suffering of others by convincing ourselves they must have done something stupid to be in this position, and, therefore, we’re safe as long as we keep on going hard. It’s just a trick to make us feel safer, that unwittingly keeps us from too consciously noticing the floods and fires, layoffs and illnesses lapping at our heels.

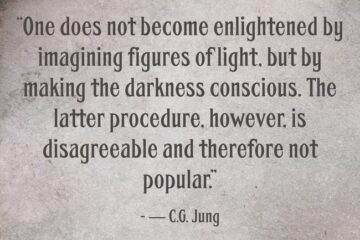

SHADOW SELF

A century ago, Carl Jung wrote that our projections are the part of us that we have disowned, that we won’t admit to ourselves. This insecurity around our future is a very human fear that we quickly insist doesn’t affect us because of course we won’t ever make those mistakes!

Except sometimes shit just happens to us.

Beyond the powers that be, we’re all fallible, and we will make mistakes. Policing ourselves for abject perfection won’t save us from error, instead it just imprisons us within our own derision. It’s hard to feel compassion for imperfections in a competitive society, both with others and within ourselves. That outer shaming and judgment comes ricocheting right back to us. Jung explains,

“A man who is unconscious of himself acts in a blind, instinctive way and is in addition fooled by all the illusions that arise when he sees everything that he is not conscious of in himself coming to meet him from outside as projections upon his neighbour” (CW, Vol 13, 391).

Our outer attitudes and actions mirror what goes on inside. The kinder and more accepting we are of others, the less judgmental we are with ourselves. The corollary: the more we can show acceptance to ourselves, the more merciful our society can become.

Years ago I saw a Jungian analyst who told me to keep a little bird on my shoulder, watching everything I do. Whenever it would notice me feeling irritated by another, the task was to look at myself to see it’s something in me that was the real cause of my ire. Exploring our darkest recesses can be a painfully difficult thing to do. But if we can realistically access ourselves, it can bring us off our pedestal and back onto the ground with the rest of humanity.

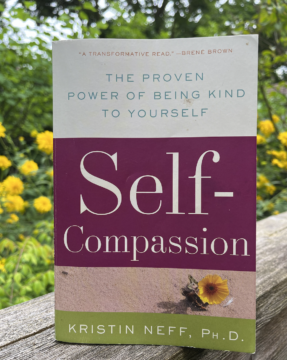

The spoonful of sugar necessary for that bit of medicine is self-compassion.

Luckily, there’s a great book on the importance of self-compassion and what it actually looks like. Dr. Kristin Neff’s 2011 book is an excellent primer with a companion website full of exercises. She recognizes that, “People who suffer from shame and self-judgment are more likely to blame others for their moral failures” (180). “When we are always seeing the worst in others, our perception becomes obscured by a dark cloud of negativity. . . . Downward social comparisons actually harm rather than help us . . . creating and maintaining the state of disconnection and isolation we actually want to avoid.” (21). If we turn our back on that rat race treadmill, we can see that being human means accepting being average and ordinary.

RESISTANCE TO SELF-COMPASSION

Neff addresses the considerable resistance to self-compassion: the fear that compassion will make us lazy or selfish and the decades of lauding self-esteem instead.

We think self-criticism keeps us on our toes. People “worry that they will become weak, or that they will be rejected, if they don’t use self-criticism as a way of addressing personal shortcomings” (128). But Neff describe that as,

“a type of safety behavior designed to ensure acceptance within the larger social group. . . . I’m going to beat you to the punch and criticize myself. . . . Hopefully you will then have sympathy for me instead of judging me. . . . This defensive posture stems from the natural desire not to be rejected and abandoned. . . . Children start to believe that self-criticism will prevent them from making future mistakes, thereby circumventing others’ criticism” (24-26).

Studies show criticism doesn’t actually make us better, but propels us into self-verification traps, in which we seek out people who agree with our self-criticisms:

“Highly self-critical people tend to be dissatisfied in their romantic relationships because they assume their partners are judging them as harshly as they judge themselves. . . . They seek to interact with others who dislike them, so that their experiences will be more familiar and coherent” (30-1).

When people start having compassion for themselves, they get a backdraft of more intense negative emotions “as if their sense of self has been so invested in feeling inadequate that this ‘worthless self’ fights for survival when it’s threatened” (131). But it’s possible to move beyond this stage: “Motivation for self-compassion shifts from ‘cure’ to ‘care’. The fact that life is painful, and that we are all imperfect, is then fully accepted as an integral part of being alive” (132).

As a teacher I used to ask grade 12 students to write about their biggest fears for the future. Typically I heard worries about getting into university, doing well, and making friends, with one or two raising more global issues. Then I’d ask what they do to try to soothe this anxiety, and all their answers go down the path of “Do everything perfectly!” They’re going to work so hard and conscientiously and do all the things necessary so only good things ever happen to them. I remind them that they can do everything to their best ability and still not do well and that they’re likely to make a mistake along the way here and there because we can’t maintain that level of self-scrutiny. That’s a hard pill to swallow. So instead of aiming at perfection, the alternative is accepting that crap is going to come our way, and practice self-comfort while we learn to pivot down a different direction if necessary, get support from others, and take a breath to get some perspective on it all. We can cope with our own fallibility.

Like the fear of weakness, the push for high self-esteem has taken us down the wrong path, leading to traps like “narcissism, self-absorption, self-righteous anger, prejudice, discrimination” (8), but with self-compassion, “when your heart opens–you immediately feel more connected, alive, present” (10). I love that she takes on the whole self-esteem industry because I’ve seen what it does when kids get marks they know they don’t deserve or participation awards. The “ego flattering” knocks them down under a layer of shame where they realize their authentic efforts won’t be recognized anyway, so why bother trying. It has “led to a worrying trend toward increasing narcissism” (146) from things like getting a 70 in a class they barely attended. More importantly, it’s a problem to teach kids to feel good when they succeed and feel bad when they fail instead of feeling good when they put in their best effort (148). We’re unwittingly training people to have contingent self-worth.

And, wouldn’t you know it, self-esteem initiatives have been a total failure:

“If anything, high self-esteem appears to be the consequence rather than the cause of healthy behaviours. . . . Bullies are just as likely to have high self-esteem as others. . . . People with high self-esteem are just as prejudiced . . . also engage in socially undesirable behavior such as cheating on tests just as often as people with low self-esteem do. . . . High self-esteem isn’t associated with being a better person, just with thinking you are” (137-140).

But self-compassion initiatives actually help. In one study,

“Students were asked to write an answer to that dreaded but inevitable interview question, ‘please describe your greatest weakness.’ Afterward they were asked to report how anxious they were feeling. Participants’ self-compassion levels, but not their self-esteem levels, predicted how much anxiety they felt. Self-compassionate students reported feeling less self-conscious and nervous that those who lacked self-compassion, presumably because they felt okay admitting and talking about their weak points” (153-154).

Neff found self-compassion helps people better accept who they are regardless of the praise or criticism they get from others, and they have less of a need to be right. This “enables people to ask for the help and guidance they need, because they’re less worried about looking incompetent for not already knowing the right answer” (169).

The idea that self-compassion will strip away motivation comes from a social structure that depends on punishment and force. But caring about self and others and a general interest in being an active member of society can be very motivating. We don’t need to beat ourselves up to get going each day. We need to heal our wounds.

THREE “DOORKNOBS” OF COMPASSION

Neff boils self-compassion down to developing kindness, a common humanity, and mindfulness.

Kindness for ourselves means being moved by our own pain and comforting ourselves, the way we would for a dear friend, regardless of what may have caused the problem. Even those of us who didn’t get enough compassion from others over the years can learn to give ourselves care and understanding. In one study, people in an fMRI were asked to react in a kind or self-critical way:

“Self-criticism was associated with activity in the lateral prefrontal cortex and dorsal anterior cingulate–areas of the brain associated with error processing and problem solving. Being kind and reassuring towards oneself was associated with left temporal pole and insula activation–areas of the brain associated with positive emotions and compassion. Instead of seeing ourselves as a problem to be fixed, therefore, self-kindness allows us to see ourselves as valuable human beings who are worthy of care. When we experience warm and tender feelings toward ourselves, we are altering our bodies as well as our minds” (49).

She asks us to put aside any blame for a minute to just acknowledge our own need for comfort. “Start being kind to ourselves when confronting our limitations, and we can suffer less because of them” (51). In three simple steps: notice when you’re being self-critical, soften that voice and shift to non-judgmental language, and then “reframe the observations made by your inner critic in a kind, friendly, positive way” (54). Imagine a little kid struggling to do something difficult. Yelling at them or calling them names or implying that they should be able to do it doesn’t help them figure it out. But taking a moment to validate how hard it is and offer some gentle encouragement can reset their brain for problem-solving instead of defense. Yet so many of us still think that criticism is necessary motivation when it comes to our own failings.

“We are healed from suffering only by experiencing it to the full” – Marcel Proust (p. 105).

Neff further explains that having a common humanity acknowledges that compassion is relational, meaning ‘to suffer with‘. I found this part of the book particularly insightful as it recognizes that our social training around production and competition has exacerbated our problems. When our self-worth is based on external success, then we form internal tyrants and turn our back on the full range of human experience.

Acknowledgment of the interconnected nature of our lives–indeed of life itself–helps to distinguish self-compassion from mere self-acceptance or self-love. . . . Self-compassion remembers that everyone suffers, and it offers comfort because everyone is human. . . . The beauty of recognizing this basic fact of life is that it provides deep insight into the shared human condition” (60-61).

We didn’t choose our genetic makeup or upbringing or environment, yet we tend to blame ourselves for our dilemmas as if we’re separate from everything surrounding us. “When wrongdoers are treated with compassion rather than harsh condemnation, cycles of conflict and suffering can be broken” (72-74). In an exercise, she suggests we notice something we judge ourselves for, and how often, and then think of who we are when we don’t display this trait. Consider the circumstances that provoke it and early conditioning that might have developed it to help recognize that it’s not entirely from us. Then shift our thinking of the trait as an identity (I’m an angry person) to a behaviour that comes and goes (sometimes I get angry) to get more distance and freedom from it. If it’s something we do and not something we are, then there’s more room for change (77).

Like Jungian shadow work, having compassion for the self leads to compassion for others as we begin to understand that everyone is a product of so many different forces. We still have to take responsibility for our actions, fixing the problems we cause along the way, but that’s different from taking on blame and shame. She describes her own difficulties with parenting and how much it helped to realize that all parents are struggling with something. In contemplating this, it helps become more “deeply in touch with the unpredictability of being human” (78).

“You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf!” – Jon Kabat-Zinn

Finally, she gets to mindfulness, which she defines as a internal self-awareness: “to hold our experience in balanced awareness, rather than ignoring our pain or exaggerating it” (41), to help us get to a form of meta-awareness “observing what is going on in our field of awareness just as it is” (85-86). We tend to focus on our failures instead of the emotional pain caused by them, and then risk burnout. We need to check in on ourselves to notice what’s happening, like watching a movie and suddenly seeing the characters as actors: “When you focus on the fact that you are having certain thoughts and feelings, you are no longer lost in their storyline” (87).

She uses the imagery of a bird as an emotion flying across the sky of awareness. Sometimes it’s more of a tornado than a starling, but it can help to picture how our mind gives us information from time to time that’s telling us about something we need or something we fear. By staying aware of our inner state, it helps us to respond rather than react to events. We can notice our defensiveness or pride or fear with curiosity (what’s that about), without letting it drive our behaviour.

“We need to be able to ask ourselves–what is really happening right here, right now? Is the danger real, or am I only having thoughts of danger, like pixels of light dancing on a screen? What is the actual situation that needs to be responded to? This is how we gain the freedom needed to make wise choices. . . . We can soothe and comfort ourselves with compassionate understanding. We can reframe our situation in light of our shared humanity, so that we don’t feel so isolated by adversity. Not only am I suffering. I am aware that I am suffering, and therefore I can try to do something about it. . . . Our emotional suffering is caused by our desire for things to be other than they are. . . . Pain is unavoidable; suffering is optional” (91-94).

One exercise she offers it to become aware of the most intense emotional buttons, accept that we sometimes overreact when they’re pushed, and then “identify what you’re craving (validation, care, support, etc.), and see if self-compassion can help give it to you” (225) in order to reduce the power of that trigger. Thinking about ourselves in a nonjudgmental way can be a useful way of exploring kindness, humanity, and mindfulness by acknowledging our human fallibility with compassion.

Beyond general mental health, compassion can help to stop rumination. Trying to eliminate or ignore negative feelings keeps them circling back to us over and over, but acknowledging them with gentle reassurance, remembering we’re all going to make mistakes and we can all be forgiven. We have no ability to get rid of emotions by burying them, as that extra layer of effort to keep them down makes them stronger. “The beauty of self-compassion is that instead of replacing negative feelings with positive ones, new positive emotions are generated by embracing the negative ones. The positive emotions of care and connectedness are felt alongside our painful feelings” (116-117). Those difficult feelings might not completely go away, but their edges can start to soften, making them more bearable.

Beyond general mental health, compassion can help to stop rumination. Trying to eliminate or ignore negative feelings keeps them circling back to us over and over, but acknowledging them with gentle reassurance, remembering we’re all going to make mistakes and we can all be forgiven. We have no ability to get rid of emotions by burying them, as that extra layer of effort to keep them down makes them stronger. “The beauty of self-compassion is that instead of replacing negative feelings with positive ones, new positive emotions are generated by embracing the negative ones. The positive emotions of care and connectedness are felt alongside our painful feelings” (116-117). Those difficult feelings might not completely go away, but their edges can start to soften, making them more bearable.