by Tim Sommers

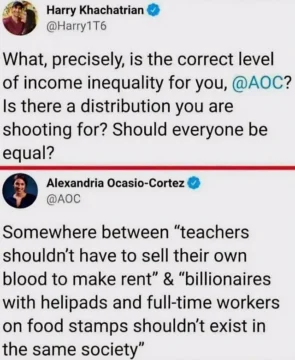

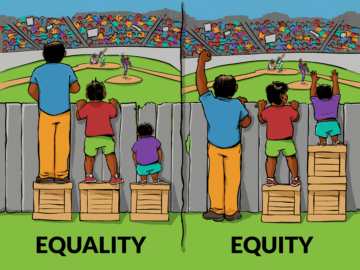

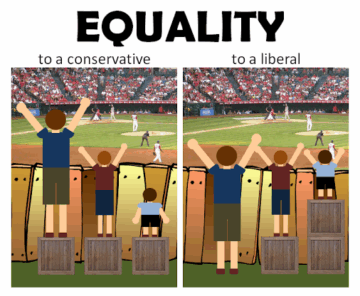

The economy is not a force of nature. We have some control over it. Granted, it’s also not like a machine controlled directly by levers, switches, and buttons either. But when the state acts, intentionally or not, it often influences the distribution of income and wealth. More often than not, it influences the distribution of wealth and income in reasonably predictable ways. It seems to me that, for this reason alone, we should care what the ideal distribution of wealth should be. The ideal distribution is, at a minimum, one factor we have an ethical obligation to take into account in governing.

Some people say that any ideal distribution is unrealistic, impossible to achieve. That’s alright though. Ideals – perfectionism, utilitarianism, the Ten Commandments – are, as they say, honored as much in their breach. We should still have ideals to follow.

Others say that trying to enforce any particular distribution – equality, first and foremost – leads to coercion and political oppression. I think they say this mostly because they have frightening real-world cases in mind. But people also do terrible things in pursuit of freedom, justice, or whatever.

You certainly can pursue equality in a repressive way. Say, seize everyone’s property, redistribute it, and redo that every so often to maintain equality. But you could also, as I implied above, mostly regard equality (or whatever the correct principle is) as a kind of tie-breaker. For example, the point of health care is not the distribution or redistribution of wealth per se, but when you must decide between two approaches one of which takes you closer, the other further away, from the ideal distribution, there’s nothing repressive about going with the one that also has a positive effect on the distribution of wealth and income. In other words, there is nothing inherently oppressive about pursuing more distributive equality. It just depends on how you do it. Read more »

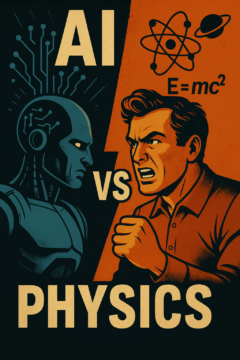

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting.

There has long been a temptation in science to imagine one system that can explain everything. For a while, that dream belonged to physics, whose practitioners, armed with a handful of equations, could describe the orbits of planets and the spin of electrons. In recent years, the torch has been seized by artificial intelligence. With enough data, we are told, the machine will learn the world. If this sounds like a passing of the crown, it has also become, in a curious way, a rivalry. Like the cinematic conflict between vampires and werewolves in the Underworld franchise, AI and physics have been cast as two immortal powers fighting for dominion over knowledge. AI enthusiasts claim that the laws of nature will simply fall out of sufficiently large data sets. Physicists counter that data without principle is merely glorified curve-fitting. The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random.

The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random. Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024.

Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024. In a previous essay,

In a previous essay,

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

We humans think we’re so smart. But a

We humans think we’re so smart. But a Giant Tarantulas

Giant Tarantulas

by Steve Szilagyi

by Steve Szilagyi