by Mark R. DeLong

1.

Regular snowmobile trails bored us kids in the closing years of the 1960s. They wound through the woods, dipping here and there just enough to stall my uncle’s boxy old Evinrude machine with its odd orange and too smooth track. My cousins and I wanted slopes—frozen white waves—to test our snow jets as if we had exchanged whining two-cycle engines for surfboards and were scaling waves on Hawaii’s North Shore. The slopes we chose in winter were man-made and, now that I look at them, rather tame. Before winter idled roadbuilding, earthmovers had cut paths for a new “Interstate” outside of town, pushing the hills into the valleys and leaving steeper cut-off grades to bound highway lanes; the earthmovers leveled the roadway through the landscape. For a winter in the 1960s, the highway’s deer fence still lacked, so we could sneak through and leap our snowmobiles over the edge of the snowy wave. We carved track parabolas up to its crest.

That was the story of I-35 near Moose Lake, Minnesota, where I was a child—at least before the wide interstate pavement opened to cars. I’m certain Moose Lake’s town council didn’t have as much fun with the interstate as I did with my cousins that winter. They knew what would happen to town traffic and businesses once the highway opened. It would dwindle and the town with it. The same story played out wherever a “superhighway” cut through the landscape.

They tried to avoid having their town turn into another small place where a gas station or two near the highway ramps would become the only retail businesses, and they had a plan. One could say they hijacked highway traffic to run through the town’s center on two-lane US Highway 61. You couldn’t exit and re-enter the new highway at the same interchange; whoever would get off I-35 would have to run through town to re-enter the interstate on an on-ramp at the opposite end.

It was a cunning plan. It didn’t work. Read more »

When you walk through the gates to enter the B-52 Victory Museum in Hanoi, you immediately find the wreckage of what has been one of the most terrifying machines ever built: an American Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. Apparently, this wreckage largely came from Nixon and Kissinger’s “Christmas Bombings” of 1972.

When you walk through the gates to enter the B-52 Victory Museum in Hanoi, you immediately find the wreckage of what has been one of the most terrifying machines ever built: an American Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. Apparently, this wreckage largely came from Nixon and Kissinger’s “Christmas Bombings” of 1972.

Throughout most of the UK (Northern Ireland is

Throughout most of the UK (Northern Ireland is

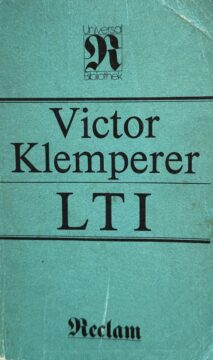

In June 1932, half a year before Adolf Hitler was sworn in as German Chancellor, Victor Klemperer watched Nazis on a newsreel marching through the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. A professor of Romance languages at the Technical University of Dresden, whose area of specialization was the 18th century and the French Enlightenment, Klemperer (1881-1960) was unpleasantly gripped by this first encounter with what he termed “fanaticism in its specifically National Socialist form,” and by the “expression of religious ecstasy” he discerned in the eyes of a young spectator as the drum major passed by, balanced precariously on goose-stepping legs while he robotically beat time.

In June 1932, half a year before Adolf Hitler was sworn in as German Chancellor, Victor Klemperer watched Nazis on a newsreel marching through the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. A professor of Romance languages at the Technical University of Dresden, whose area of specialization was the 18th century and the French Enlightenment, Klemperer (1881-1960) was unpleasantly gripped by this first encounter with what he termed “fanaticism in its specifically National Socialist form,” and by the “expression of religious ecstasy” he discerned in the eyes of a young spectator as the drum major passed by, balanced precariously on goose-stepping legs while he robotically beat time. When my mother was a teenager in the early 1940s, a NY-area radio station ran a weekly contest, asking listeners to vote for their favorite singer among two: Crosby or Sinatra? How people made this preference known remains unclear to me: did you need a phone in your house to make a call to the station or was sending a postcard enough? Whatever the method, the winner would be announced each Sunday afternoon. While Sinatra often took the prize, Crosby occasionally outpaced the Jersey boy who grew up two towns south of Cliffside Park, my mother’s hometown. On those occasions, she told me, she’d stamp around my grandparents’ railroad apartment, enraged at the abject stupidity of her fellow listeners. When she’d tell this story, my mother would marvel at her parents’ forbearance, the way they’d accept these outbursts without comment, though they were highly disciplined, gloomy people for whom the idea of having an “idol,” or caring about his fate on a weekly radio show was surely alien. I like this insight into them, a softer side that I myself had only witnessed a few times.

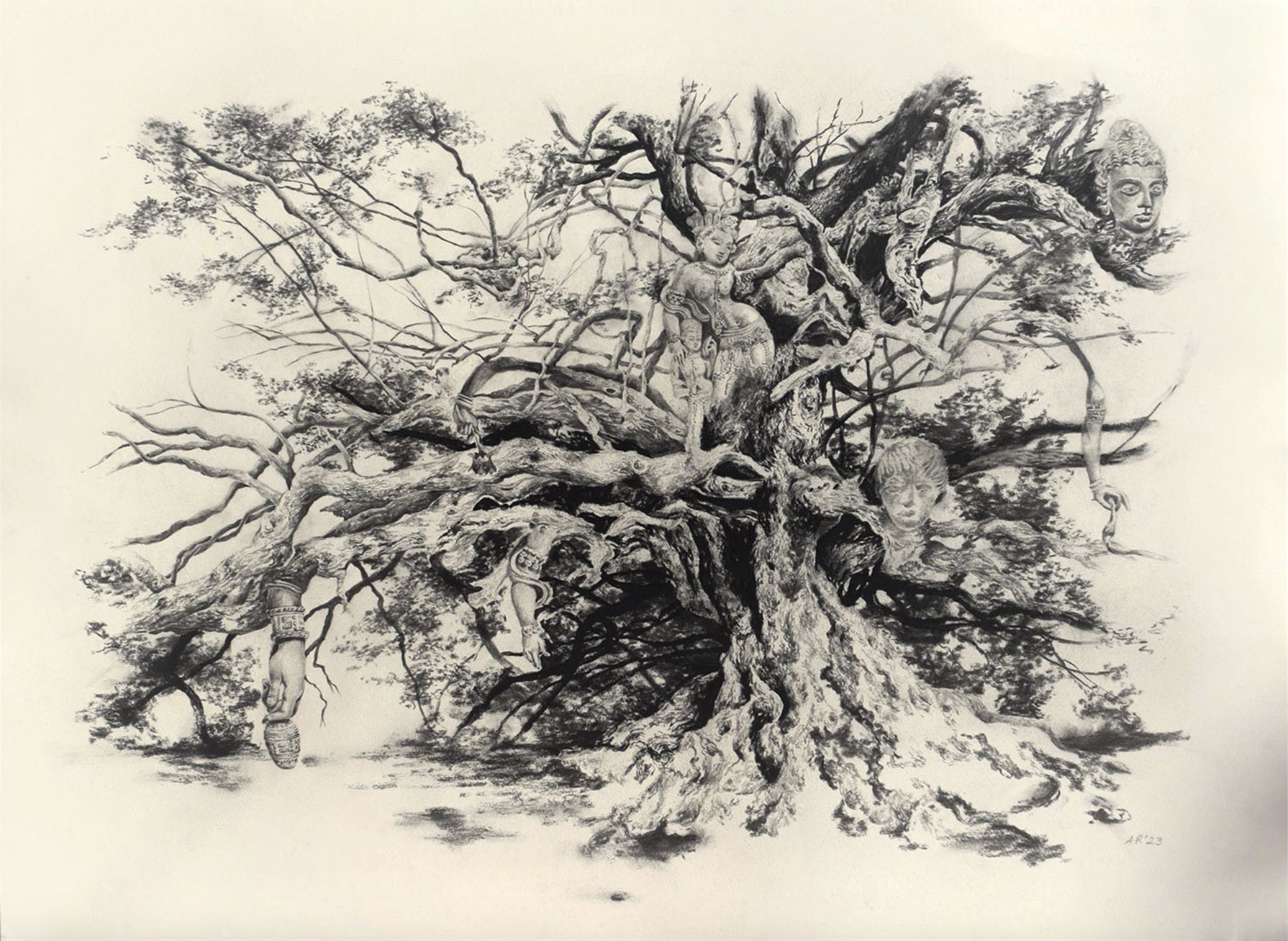

When my mother was a teenager in the early 1940s, a NY-area radio station ran a weekly contest, asking listeners to vote for their favorite singer among two: Crosby or Sinatra? How people made this preference known remains unclear to me: did you need a phone in your house to make a call to the station or was sending a postcard enough? Whatever the method, the winner would be announced each Sunday afternoon. While Sinatra often took the prize, Crosby occasionally outpaced the Jersey boy who grew up two towns south of Cliffside Park, my mother’s hometown. On those occasions, she told me, she’d stamp around my grandparents’ railroad apartment, enraged at the abject stupidity of her fellow listeners. When she’d tell this story, my mother would marvel at her parents’ forbearance, the way they’d accept these outbursts without comment, though they were highly disciplined, gloomy people for whom the idea of having an “idol,” or caring about his fate on a weekly radio show was surely alien. I like this insight into them, a softer side that I myself had only witnessed a few times. Anushka Rostomji. Waq Waq Tree, 2023, of the Flesh and Foliage Series.

Anushka Rostomji. Waq Waq Tree, 2023, of the Flesh and Foliage Series.

Jersey City is a medium-size city on the West bank of the Hudson River across from Lower Manhattan. Up through the middle of the 20th century it was a port and a railroad hub but that disappeared when containerized freighter became too deep to travel that far up New York Bay. Without any freighters the railroads were no longer needed. Light industry disappeared as well. Jersey City became back-offices and bedrooms to Manhattan-based business.

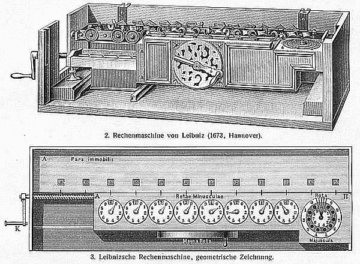

Jersey City is a medium-size city on the West bank of the Hudson River across from Lower Manhattan. Up through the middle of the 20th century it was a port and a railroad hub but that disappeared when containerized freighter became too deep to travel that far up New York Bay. Without any freighters the railroads were no longer needed. Light industry disappeared as well. Jersey City became back-offices and bedrooms to Manhattan-based business. We have slid almost imperceptibly and, to be honest, gratefully, into a world that offers to think, plan, and decide on our behalf. Calendars propose our meetings; feeds anticipate our moods; large language models can summarize our desires before we’ve fully articulated them. Agency is the human capacity to initiate, to be the author of one’s actions rather than their stenographer. The age of AI is forcing us to answer a peculiar question: what forms of life still require us to begin something, rather than merely to confirm it? The best answer I’ve been able to come up with is that we preserve agency by carving out zones of what the philosopher

We have slid almost imperceptibly and, to be honest, gratefully, into a world that offers to think, plan, and decide on our behalf. Calendars propose our meetings; feeds anticipate our moods; large language models can summarize our desires before we’ve fully articulated them. Agency is the human capacity to initiate, to be the author of one’s actions rather than their stenographer. The age of AI is forcing us to answer a peculiar question: what forms of life still require us to begin something, rather than merely to confirm it? The best answer I’ve been able to come up with is that we preserve agency by carving out zones of what the philosopher

When promoting her new book in September, Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett stated in an interview as quoted in Politico : “I think the Constitution is alive and well.” She went on – “I don’t know what a constitutional crisis would look like. I think that our country remains committed to the rule of law. I think we have functioning courts.”

When promoting her new book in September, Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett stated in an interview as quoted in Politico : “I think the Constitution is alive and well.” She went on – “I don’t know what a constitutional crisis would look like. I think that our country remains committed to the rule of law. I think we have functioning courts.” During covid, amid the maelstrom that was American healthcare, a miracle happened. State medical boards suspended their cross-state licensure restrictions.

During covid, amid the maelstrom that was American healthcare, a miracle happened. State medical boards suspended their cross-state licensure restrictions.