by Leanne Ogasawara

Idray Novey Ways to Disappear

Jennifer Croft The Extinction of Irena Rey

Haruki Murakami on The Great Gatsby

1.

A translator living in Pennsylvania is worried, because her favorite client is missing. And it’s not just any client but the Brazilian cult novelist Beatriz Yagoda whose work the translator has labored on for years. For peanuts too.

And when I say peanuts I mean that the author and the translator each get about $500 per book! As a translator with a manuscript of poetry translations of my own ready-to-go, I know that if I ever do try to shop it around, I’d be lucky to get even that much. Translation does not pay. And neither does poetry… I am on a ten-week fellowship with ten other artists, and one of the more successful writers here, a poet with a fabulous publisher, said she is turning to novels since she learned first-hand how little poetry pays, and I wondered does fiction really pay then? But I digress.

So our American translator immediately books a ticket to Rio. I mean, what’s she supposed to do? She feels without a shadow of a doubt that being the author’s translator, only she “truly understands” the author and is therefore the best person for locating her.

The author’s daughter thinks this is ridiculous. She herself had never read her mother’s books. But who but a daughter knows the mother best?

She had no patience for the illusion that you could know someone because you knew her novels. What about knowing what a writer had never written down—wasn’t that the real knowledge of who she was?

Ways to Disappear is such a fantastic novel. The author Idra Novey is herself an award-winning translator. Most notably of Clarice Lispector, whose life has some resonance with the translator protagonist in Novey’s story. Both being physically beautiful and having been born outside of Brazil. I didn’t know this about Lispector that she was born in Ukraine but at an early age the family emigrated to Brazil to escape pogroms.

In one of Lispector’s novels, her protagonist says: “I can’t sum myself up because it’s impossible to add up a chair and two apples. I’m a chair and two apples. And I don’t add up,” which is maybe what the daughter of Beatriz Yagoda means when she questions the translator’s feeling that she is the only person who truly understands the author since she is the author’s translator.

How can we ever really know anyone? Or rather, how can we know whether we know? In the case of the story, maybe the translator knew the apples and the author’s daughter knew the chairs.

What I loved best about Novey’s gorgeous book (did I mention she is also a poet?) is that the translator in the story is also an aspiring writer, just like Novay herself and just like me. This transformation from translator to writer happens as the translator searches for the missing author to whom she has devoted her life. Devotion being the key word.

In Brazil, she begins to shake off the translator’s position of being “available yet silent,” where there is “no obvious spot for her to put herself,” to begin writing her own prose in her journal. So, then, is this a novel about the search of self-discovery?

The handsome son of the missing author asks her, “Do you write too?” when he spots her open journal on the bed. She says, “Oh, no, that’s nothing.” But later remarks,

traduttore, tradittore—that tired, tortured Italian cliché. If only she’d been born a man in Babylon when translators had been celebrated as the makers of new language. Or during the Renaissance, when translation was briefly seen as a pursuit as visionary as writing. She would have been in her element then. During the Renaissance, no translator had to apologize for following her instincts to champion the work of one of the most extraordinary, under-recognized writers of her time.

Oh how the mighty have fallen?

2.

If I could study creative writing with any teacher in the world it would be Jennifer Croft—and don’t think I haven’t played around with the idea either (en garde Jennifer Croft!) I have heard it said (I think in a review in the Guardian) that she is our greatest living translator. She is well-known for her work translating Poland’s Nobel Prize-winning author Olga T. as well as for her vocal campaign to get translators’ names on book covers, where they should be!

Like Novey’s novel, Croft’s The Extinction of Irena Rey begins with a missing author, which, if you think about it, is such a great metaphor for feeling lost and having the ground pulled out from beneath one’s feet). But this time, the author is not a cult classic writer in Brazil but a famous Polish Nobel Prize contender, considered one of the greatest living writers on earth. In Croft’s novel, the protagonist is not one lonely translator, but the Polish star’s entire team of translators. This author is like a corporation and when a new book is about to come out, she gathers her group of Anglo-European translators at her lodge on the edge of the last surviving primeval forest in Europe to create the new translations, working together to solve problems and help ensure quality control — exerted all kinds of control in the process. When the author disappears, things spin out of control with her multi-lingual army, and it quickly becomes a very wild ride.

I used to think that life is itself translation, since we all translate our experiences into some kind of narrative or truth. I no longer think this, but I do feel translation is a powerful metaphor for how we live our inner lives. There were so many themes in her marvelous novel but one I was especially drawn to was the way art (and all of life really) is part of a process of creation and destruction—translation in so many ways is a taking apart and putting back together again. The Spanish language protagonist says,

Art is the uniquely human impulse to relentlessly transform whatever we come into contact with, to undo in order to do a redo. To create, we first have to destroy.

What is artistic integrity and how much of the art belongs only to the artist? Some could say that nothing new is ever created by the human mind. Everything in the world is in flux, and knowledge too is recycled— reincarnated and reborn. Blended with something else, new knowledge or any vision in science and art might appear new, but everything filters down to us from our ancestors before us. And just as Julius Caesar followed in Alexander’s footsteps, so too did their author make use of the lives of her translators! The great stroke of genius in the book is that it is presented as a book in translation, written by Spanish, and the translator that we are reading is her rival English, who has added dozens of footnotes, some are so hilarious I couldn’t stop laughing, while others provide an idea of the kinds of problems and decisions real-life literary translators must make on every page.

This novel is so much fun!

3.

I was recently reading a fantastic book of essays about literary translation called In Translation: Translators on Their Work and What It Means edited by Esther Allen and Susan Bernofsky, and realized something new about Haruki Murakami. I knew that Murakami was an accomplished translator of American novels into Japanese –famously of The Great Gatsby—but I never realized his deep love of American fiction.

Did you know that by the time he was in is thirties, he’d already made an oath to himself translate The Great Gatsby into Japanese by the time he was sixty. This was a promise so solemn that he placed his Japanese copy of the novel on the kamidana in his home, the shelf usually reserved for honoring the Shinto gods.

Translation is, after all, the most intimate kind of reading and also the most rigorous form of textual analysis. I say that without any qualification—because I think it is true.

In the introduction to his translation, Murakami writes of being deeply impressed when he learned that Hunter S. Thompson typed out the entirety of The Great Gatsby, end to end, before he’d ever written a book of his own, just to see what it felt like. In my essay in the Millions about writing workshops, which I have referred to time and again in these pages, I mentioned how I was given exactly this same advice when I started playing around with the idea of becoming a novelist—not once but twice!

“Whatever you do, don’t get an MFA”

And

“Don’t show anyone your work, other than a few trusted friends”

And

“If you really want to learn how to write, copy out a favorite book by hand.”

Translation is like that: a deep read. More, it is an internalization of the text… breathing in the original version and eventually (after being fully digested) exhaling the translation, but as others have written time and time again, every translation is a failure of some kind, something is inevitably lost in translation, as every translation in is somehow necessarily imperfect. Knowing this, for his Gatsby translation, Murakami decided to focus on musicality. That is, he decided when two issues are in conflict, for example, meaning versus sound, he always chose the latter.

Often translators have to make these kinds of global decisions. When I worked on Takamura Kotaro’s Chieko Poems, I made a very conscious decision, knowing that something would have to give, to place my emphasis on the images of his poems. Also a sculptor, Kotaro works in these unforgettable images. Like that of a woman on her deathbed biting into a lemon, or the ice on the River Jordan. He also has a unique tone and voice that varies from poem to poem. So, I tried to convey that as best as I could. Maybe sound or sentence structure had to give though…?

In addition to the musicality of the sentences, Murakami also wanted to create a work that wasn’t frozen in time. He writes that translations have their expiration dates. And I do agree that reading a Victorian rendition of the Tale of Genji is startling. It might not really work as well today as the newer, updated translations. It is interesting to think that while novels do not usually have “best by” dates, translations do go out of style.

So how do you think Murakami translated the phrase made famous by Fitzgerald: “old sport?”

Yep, he left it in English.

So, Dear Reader, if you were going to pick one book to inscribe onto the pages of your heart and make truly your own, what would it be? For Murukami it was, The Brother’s Karamazov, Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye, and of course, Gatsby.

Mine would also include the Brothers Karamazov, but the two I would bring with me to a desert island would be the Quixote, and the Kokinshu poetry anthology. The last one is the only one I would choose to try and translate, but if I could set a real goal, I would like to translate the poetry of Du Fu or Li Qingzhao. Someday…..I am embarking on an online study of classical Chinese in order to begin this impossible journey. To learn to write, though, I think I would choose Irena Rey. How about you?

++

Notes:

1. The Booker Prize: I was so disappointed Croft’s novel wasn’t on the Booker Prize Longlist. But I am loving the list this year, and so far, Hasham Matar’s My Friends is my top choice… I was thrilled that Samantha Harvey’s Orbital was there and also really admired Enlightenment by Samantha Perry. Percival Everett is one of my favorite writers so was happy about that choice too and am currently reading Claire Messud’s fabulous new novel This Strange Eventful History.

Do you have any favorites from the list?

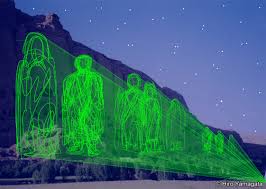

2. Regarding art as destruction and recreation, I realized that my first post in these pages was about the destruction of the Bamiyan statues and it led (in comments) to an interesting conversation about the Buddhist concept of impermanence.