by Andrea Scrima

In many ways I was lucky: I was neither raped, trafficked, nor bitten on the genitals so hard that I bled, an image that emerged from a trove of emails recently released from the Epstein files detailing alleged acts of abuse by billionaire Leon Black, who was forced to step down as chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2021. I wasn’t groped or forced to undress or perform a sexual act on myself or my predator. I’d incurred no physical injuries or bruises; the damage he did was of a different kind.

When his name turned up recently, attached to a prestigious new prize for young artists, I was sure I was mistaken; after a quick internet search revealed that it was, in fact, the same man, it took me some time to process the discovery. From one moment to the next, I found myself staring at the college graduation photograph of a man I’d done my best to forget, and although he was in his late thirties when I met him, I recognized the face immediately. I was an eighteen-year-old painting major writing long-form poetry, he was the head of the poetry seminar I wanted more than anything to get into. I see him standing opposite me in a turtleneck sweater. He’d already heaped praise on my work; he had, in fact, chosen me from that year’s crop of young art students. Not as a prodigy to mentor, as I would soon discover, but as a sexual interest. When I turned down his advances, he refused to let me into the class.

He’s been dead for three or four years now; a rather sizeable legacy funds at least two major awards in his name: one in the visual arts, the other in literature. Staring at his obituary, trying to make sense of my emotions, I was haunted by memories I hadn’t had access to in decades. I let a few days pass, and then I mailed an editor at an art magazine I work with, briefly outlined what happened, and asked if this was just another one of those countless #MeToo stories and if there was any point in writing it—as far as pitches go, it was hesitant, reluctant. As it turns out, there are several fairly serious sexual abuse scandals connected to the art school I was enrolled in at the time, and so the editors were indeed interested and I did, in fact, wind up writing the piece, which will be published in the aforementioned magazine in March. But this essay is a different essay, one about writing that essay: the uncertainty that suddenly nagged at me, the sense of not being believed or even particularly believable, the lingering feeling of shame that nearly all victims of sexual predation carry with them, years and even decades later. Read more »

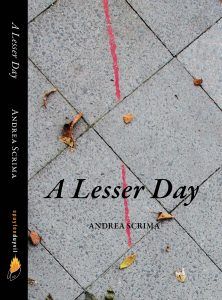

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.