INTERVIEW BETWEEN ANDREA SCRIMA (A LESSER DAY)

AND CHRISTOPHER HEIL (Literaturverlag Droschl)

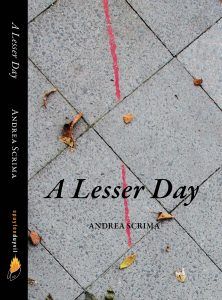

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

When she looks back over more than fifteen years from the vantage of the early 2000s and revisits an era of personal and political upheaval, it’s not an ordering in the sense of a chronological sequence of life events that the narrator is after. Her story pries open chronology and resists narration, much in the way that memories refuse to follow a linear sequence, but suddenly spring to mind. Only gradually, like the small stones of a mosaic, do they join to form a whole.

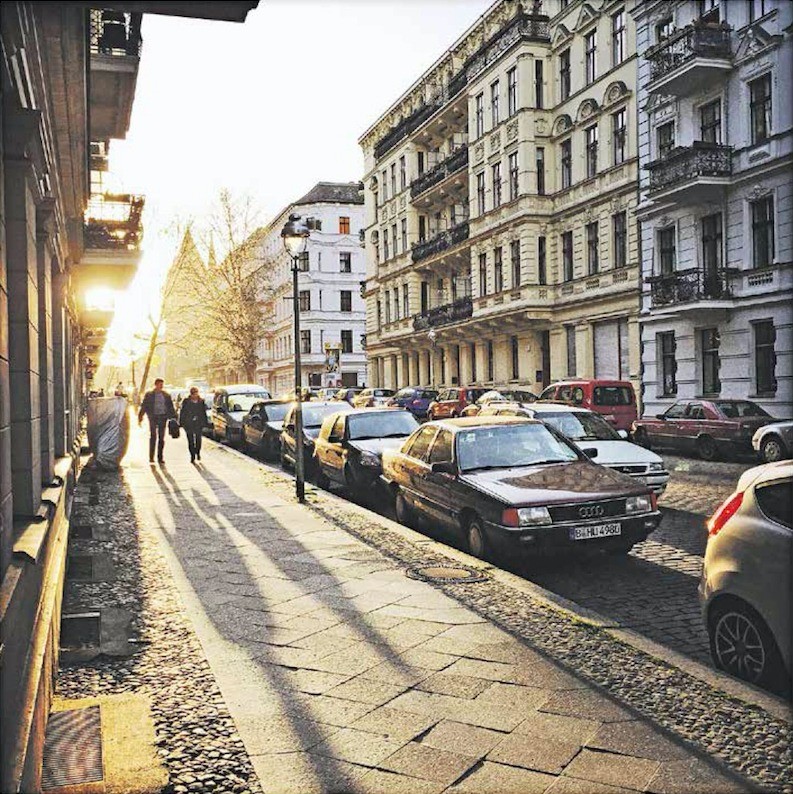

In 1984, a crucial change takes place in the life of the 24-year-old art student: a scholarship enables her to move from New York to West Berlin. Language, identity, and place of residence change. But it’s not her only move from New York to Berlin; in the following years, she shuttles back and forth between Germany and the US multiple times. The individual sections begin with street names in Kreuzberg, Williamsburg, and the East Village: Eisenbahnstrasse, Bedford Avenue, Ninth Street, Fidicinstrasse, and Kent Avenue. The novel takes on an oscillating motion as the narrator circles around the coordinates of her personal biography. In an effort of contemplative remembrance, she seeks out the places and objects of her life, and in describing them, concentrating on them, she finds herself. The extraordinary perception and precision with which these moments of vulnerability, melancholy, loss, and transformation are described are nothing less than haunting and sensuous, enigmatic and intense.

Christopher Heil:

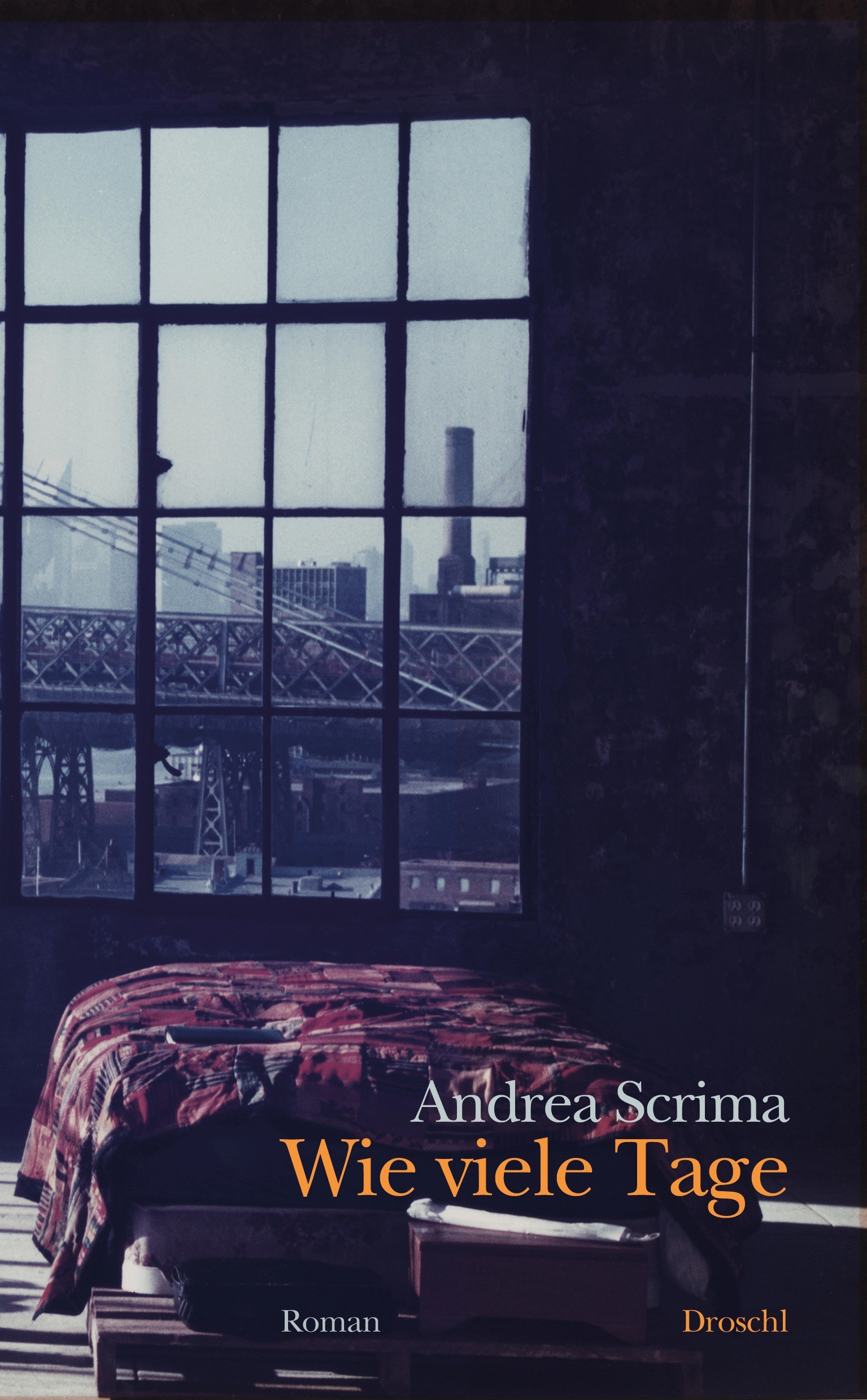

In A Lesser Day, certain parallels between the narrator and author become evident. In a conversation we had last year over genre, as we were preparing the German edition (Wie viele Tage, Literaturverlag Droschl, 2018), you said that the term “novel” would probably come closest, although various autobiographical aspects serve as points of departure for the fictional text. In 1984 you received a scholarship to the Hochschule der Künste in West Berlin; your original home is in the fine arts. How and when did you first begin writing?

Andrea Scrima:

There are certainly parallels to my own life, but A Lesser Day is a literary project with its own set of formal and thematic concerns. For instance, the fact that I spent years working on my first book is something I’ve left out altogether, because it’s about the inner experiences of a particular artist, and not my own, although I’ve given her a good deal of my own biography.

Writing was always there. At the age of thirteen I wrote and directed two plays. One of these was a satire on Watergate, a rather silly story in which siblings spy on one another; in the end, the crime is disclosed, but not before a shockingly dysfunctional family makes its appearance on stage. At thirteen, I wasn’t aware that I was mirroring the difficult situation at home, trying to come to terms with it. I had no knowledge of psychology. My entire family was sitting in the audience; it took me years to understand that in my attempt to write my way out of the terrible pressure at home, I’d pretty much exposed them. I didn’t know back then how naked you can be in your writing. But I must have experienced a subconscious feeling of shame after all, because I didn’t pursue my career as a “celebrated” author. From the age of around fifteen, art became the all-important thing.

Despite this, though, in a way I’ve always been writing, albeit with other means. In my artistic work, references to writing emerged very early on; with time, these became increasingly dominant, to the point that I was mainly doing large-scale text installations, in other words, short stories that carried across the walls of entire rooms. Slowly, I began to understand that writing had replaced painting as my working process, my thought process.

How important is your artist’s eye for the author’s perspective? The depictions of places and objects are so intense and are described with such sensitivity and precision that while reading the book I literally wanted to reach out and touch the plaster buckling on a wall or the layers of paint on a painting’s surface.

My background as an artist has been formative for my writing, of course. A decades-long artistic practice in which you’ve worked through forms of expression as far away as possible from words and explanations leaves its traces—also within language. I harbor a faint mistrust of words; I observe to what extent language is also, to use an art term here, a readymade, how sentences often tend to carry themselves to conclusion, all by themselves—and how difficult it is to resist this autonomous force of language as a common currency. This is why in my writing meaning often arises out of descriptions of visual phenomena, the place where metaphors crystallize.

On the surface, the book is about the inner life of a young artist; it contains many descriptions of her artistic process. But I’m far more interested in the mental images that arise in the mind of the reader, because these are always far more intense.

Would you say that A Lesser Day is also an artist’s novel?

Only up to a point. In my writing, I try to capture in words the non-verbal aspects of perception, to approach the incomprehensibility of sheer reality, which words can only indirectly describe. This is chiefly a literary endeavor in which the abundance of visual description activates the reader’s sensory perception. It’s possible that my artistic background has equipped me differently, and that I react to spatial and material phenomena in a way that lends the text a dimension that goes beyond the literary. In the end, though, it’s all about language.

The period during which A Lesser Day takes place is a time of upheaval and transformation: the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, probably the most momentous change in the second half of the twentieth century. The narrator experiences all this right outside her own door. What effects do these events have on her? She’s grappling with a great deal of change in her personal life, as well: a new home on a different continent, learning a foreign language. All of this entails a degree of self-reinvention, or at least reorientation.

Again and again, world history puts in an appearance in A Lesser Day, but on the periphery of things, the periphery of perception. Despite this, it’s ubiquitous, and it forms the backdrop against which the protagonist goes about her day-to-day life. She listens to the radio as she paints: Sarajevo is under siege, snipers take aim at a playground, children die. The news is unbearable. This, too, is history: an individual’s immediate reaction to these occurrences and what that does, the long-term effect it has on the psyche.

The events described are very concrete: the fall of the Berlin Wall, the currency union, German reunification, and then, suddenly, there’s a war in Europe again. The narrator sits at a desk and cuts news photos out of the newspaper. But it’s not about how she feels; she merely registers things, takes stock. It’s not possible to describe the outrage and horror, which is why the book engages in a media-reflective description: the screened images are reconstructed soberly, painstakingly, meticulously in words, and this conversion from one medium to another also constitutes an inquiry into what, actually, is being shown to us.

I’m thinking of Hayden White’s “poetics of historiography,” which examines the different strategies of explanation employed in the recording of history. White detailed the ways in which interpreting history and the past doesn’t proceed from a pure or objective perspective, but is, in fact, a narrative, a “kind of writing” filtered through subjectivity. In my book, I counter the official historical narrative with a highly personal historiographic meta-level filtered through art.

You once said that language is crucial to identity. What form does arrival take, and what do you have to let go of? Do you feel like two different people—the American in Germany, and then the expatriate back in the US?

The “arrival” proves to be very problematic for the narrator. Early in the book, she writes about how difficult she finds this new language:

“Another official letter from the academy, full of incomprehensible words, many of which were capitalized and extended halfway across the page: perilous words, monstrous words, and I, understanding nearly no German, trying to decipher the content with a pocket dictionary.”

I didn’t give her my close familiarity with Germany; it’s only mentioned once, later on, that she’s in the process of translating a book. Language or being at home in a language or a culture other than one’s own is not the subject of this novel. But what is emphasized is that she increasingly feels like a foreigner “at home,” in other words, that she no longer has any unequivocal, exclusive allegiance. She’s not so much two people in two very different cultures, but rather one person suspended between realities for whom nothing, in a sense, is second nature.

You once spoke of the metaphysics of place. How does this relate to the book, and what role does it play for the narrator?

What I mean is a metaphysics of place in terms of how it affects the memory; the way in which a location can be both a preserver of and a trigger for memory. On the one hand, space becomes an organizing principle, also of the temporal; the various time periods in A Lesser Day are divided into the places where the narrator once lived. On the other hand, rooms are like another layer of skin: we lock ourselves away in them, sleep and dream in them; they’re very intimate. What happens to the intensity of presence a person emits when they’ve lived in a place for a longer period of time? Does the place preserve some kind of imprint of this energy? I ask myself what happens when we leave a place forever, whether we leave a part of ourselves behind and ultimately lose it.

We memorialize the birthplaces of people we revere, but we don’t really know what, exactly, we’re doing. There’s an element of the relic in this, an atavistic belief that some part of the person still somehow lingers on in a place. The house in which the narrator’s mother and grandmother grew up exists solely in the form of a gap in a sequence of house numbers on a Bronx street. When a place disappears like that—after a building has been torn down, or an entire area has been rebuilt—I wonder whether a kind of invisible trace of the original site remains, whether these mysterious coordinates, even if they’re suspended in the air or superimposed over another existing space, continue to define in some sort of cryptic way a fixed position on a planet hurtling through space, together with everything that has happened there.

We memorialize the birthplaces of people we revere, but we don’t really know what, exactly, we’re doing. There’s an element of the relic in this, an atavistic belief that some part of the person still somehow lingers on in a place. The house in which the narrator’s mother and grandmother grew up exists solely in the form of a gap in a sequence of house numbers on a Bronx street. When a place disappears like that—after a building has been torn down, or an entire area has been rebuilt—I wonder whether a kind of invisible trace of the original site remains, whether these mysterious coordinates, even if they’re suspended in the air or superimposed over another existing space, continue to define in some sort of cryptic way a fixed position on a planet hurtling through space, together with everything that has happened there.

In one part of the text, we can ascertain the year in very concrete terms: “The currency union had just gone into effect; the shops, closed down over the weekend for inventory and reopened now with new stock on the shelves, a new look of shy pride.” We’re in the summer of 1990. How should we envisage this shuttling between worlds? The narrator’s brother arrives from America in a Germany that’s immersed in the process of reunification, and she tries to explain to him what’s just taken place in the various places they visit. Is he able to understand? Because what you describe here is essentially a collision of worlds.

The brother travels to Berlin after their father has died, yet although they’re emotionally close, they fail in their attempt to establish understanding and to salvage their childhood bond and bring it into the present and allow it to grow. The narrator finds herself caught between two very different realities; she’s familiar with her brother’s perspective and cultural background, but she can’t quite explain this foreign land to him, can’t make him understand what’s actually happened. She can’t even figure out what he doesn’t understand, because she can no longer subtract the experiences of her years in Berlin and anticipate an outsider’s potential misunderstandings. The issue here is a very basic one: it’s about conveying knowledge, and whether a description or interpretation can ever take the place of personal experience—and if it can’t, what results from this attempt to explain. Historiography consists of innumerable interlocking chains of precisely this type of interpretative explanation, each of which was originally rooted in its own immediate reality.

In one of the book’s passages we read: “one Christmas superimposed upon another like a mirror with a time delay.” Can this be seen as a symbol for the narrator’s own memory? Whether in reality or imagination, she seems to move between the various locations in the book and observe her life at a remove.

I’ve often wondered what sort of temporality this book, which is written in the first person and in the present tense, actually occupies. If I were to try to reduce everything to a common denominator, I’d have to say that it’s a perception of time in which the narrator experiences the present as already, somehow, past—as though she were remembering the present from some point in the future. In other words, she experiences the fleeting nature of the present as an ongoing state of mind that she can’t shake off, the way we sometimes have a distorted perception of time following the death of a person we’ve loved. In one part of the book, the narrator feels as though she were already an old woman merely dreaming of being young; she imagines that time were tunneling back inside itself somehow, and that it’s not her father that she’s just lost, but a son.

In A Lesser Day, the narrator often addresses an unnamed “you” that oscillates between her deceased father, her brother, and one or more former lovers. These passages read like a quiet monologue held for someone who’s no longer present. How important is it to the narrator, in all her interiority, to go out of herself and speak to these absent others, even if she can’t expect any answers?

The book begins with the loss of the father, the first “you” the narrator addresses. But it soon becomes clear that this “you” is a fluid one, a merging of various persons. We’re familiar with the principle of transference in psychology. Who are we talking to when we talk to those closest to us? Is it really only about this one person, or are there others involved, superimpositions of various intimacies? The “you” in A Lesser Day is an amalgamation; it doesn’t only consist of the narrator’s deceased father or the people she’s lived with, but a series of former lovers and others she’s shared her innermost thoughts with. It’s not just a question of whom we feel close to, but rather when and why this intimacy can sometimes give way to ambivalence and longing, as though we were seeking ourselves in the other and never finding it.

In A Lesser Day, an array of various characters is described: people down on their luck, odd neighbors, misfits, crazy people. Many of them are gone or dead; most are lonely, trapped in their existence, yet every one of them craves connection, searches for ways to feel themselves—whether through alcohol, violence, or other excesses. The narrator’s own loneliness sharpens her eye for the loneliness of most of the people around her; her preoccupation with them is a tender form of intimacy, even if it occurs for the most part in her imagination.

One theme in the novel is the self-actualization that takes place between multiple homelands. How difficult or easy does the narrator find this process of growing into different worlds (New York / Berlin)? And what role does art play in this?

The narrator undergoes a process of alienation that every exile becomes haunted by sooner or later. Art is her method of negotiating reality. After her father dies, she paints relentlessly; she collects newspaper photographs for her art. She creates small sculptural objects made from the refuse of everyday life. But she’s just as interested in the brushstrokes left behind by paintings taken off a wall, the semicircle a poorly hung door digs in a linoleum floor, or the shriveled spot on a cement floor where the paint hasn’t yet dried through and hardened. This world of inner perception is just as real to the narrator as the external situation around her; it’s how she reconciles her different realities.

The narrator undergoes a process of alienation that every exile becomes haunted by sooner or later. Art is her method of negotiating reality. After her father dies, she paints relentlessly; she collects newspaper photographs for her art. She creates small sculptural objects made from the refuse of everyday life. But she’s just as interested in the brushstrokes left behind by paintings taken off a wall, the semicircle a poorly hung door digs in a linoleum floor, or the shriveled spot on a cement floor where the paint hasn’t yet dried through and hardened. This world of inner perception is just as real to the narrator as the external situation around her; it’s how she reconciles her different realities.

Andrea Scrima is an artist and writer living in Berlin, Germany.

Christopher Heil is editor-in-chief at Literaturverlag Droschl, Graz, Austria.