INTERVIEW BETWEEN ANDREA SCRIMA (A LESSER DAY)

AND CHRISTOPHER HEIL (Literaturverlag Droschl)

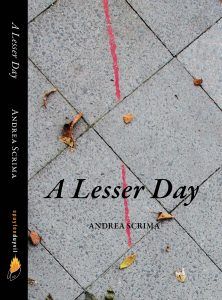

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

When she looks back over more than fifteen years from the vantage of the early 2000s and revisits an era of personal and political upheaval, it’s not an ordering in the sense of a chronological sequence of life events that the narrator is after. Her story pries open chronology and resists narration, much in the way that memories refuse to follow a linear sequence, but suddenly spring to mind. Only gradually, like the small stones of a mosaic, do they join to form a whole.

In 1984, a crucial change takes place in the life of the 24-year-old art student: a scholarship enables her to move from New York to West Berlin. Language, identity, and place of residence change. But it’s not her only move from New York to Berlin; in the following years, she shuttles back and forth between Germany and the US multiple times. The individual sections begin with street names in Kreuzberg, Williamsburg, and the East Village: Eisenbahnstrasse, Bedford Avenue, Ninth Street, Fidicinstrasse, and Kent Avenue. The novel takes on an oscillating motion as the narrator circles around the coordinates of her personal biography. In an effort of contemplative remembrance, she seeks out the places and objects of her life, and in describing them, concentrating on them, she finds herself. The extraordinary perception and precision with which these moments of vulnerability, melancholy, loss, and transformation are described are nothing less than haunting and sensuous, enigmatic and intense. Read more »