by Brooks Riley

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Jerry Cayford

I was always attracted to that old dichotomy: people must be either stupid or lying when they claim to believe some obvious falsehood. This dichotomy is a staple of Democratic theorizing about our political culture. (Sometimes the choice is between stupid and evil, which amounts to the same.) For example, Adam-Troy Castro’s social media classic “Why Do Liberals Think Trump Supporters Are Stupid?” has been circulating since halfway through Trump’s first term. But this simple dichotomy is losing its appeal. It is just not plausible that tens of millions of ordinary Republicans—our neighbors, friends, and families—are stupid or evil. There have been many proposed explanations of this puzzle: information siloes hide the obvious from otherwise intelligent people; tribalism exerts a powerful evolutionary draw. I believe, though, that there is a different and hidden complexity here.

I use the word “complexity” deliberately, because my argument draws on one of the icons of chaos theory (aka complexity theory) known as the “Coastline Paradox.” That name refers to a 1967 paper, “How Long Is the Coast of Britain?” by one of the pioneers of chaos theory, Benoit Mandelbrot. James Gleick provides a quick introduction to the topic in “The Man Who Reshaped Geometry” (1985), and a thorough treatment in his book Chaos: Making a New Science (1987). But the Coastline Paradox itself is easy to understand.

Imagine you measure the coast of Britain by putting markers every ten miles and summing the distances between them. You get a certain result. If you put markers every mile, you get a larger result. Measure the coast with a yardstick: longer still. With an inch ruler: longer. The coast will continue to get longer as you trace it around ever-smaller irregularities, around every grain of sand. So, how long is the coast? As Gleick says in his article, “In fact, it depends on the length of your ruler. As the scale becomes finer and finer, bays and peninsulas reveal new subbays and subpeninsulas, and the length—truly—increases without limit, at least down to atomic scales.” In a sense, physical length does not exist. Or, physical lengths are all infinite. Or, better, length depends on your method of measuring.

Examining length gives us a glimpse into a new picture of how the things we say and believe relate to reality. Read more »

by Charles Siegel

Oh the streets of Rome

are filled with rubble

Ancient footprints are everywhere

You can almost think

that you’re seeing double

On a cold, dark night

on the Spanish Stairs

Those are the first lines of “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” a song written by Bob Dylan in 1971. I remember that the first time I heard the tune, I thought it was by The Band, because they actually released it first in September of 1971. Two months later, Dylan’s version came out, oddly enough on the album “Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. II.”

Many artists have covered the song, most notably the Grateful Dead. They played it 144 times, according to gratefulsets.net. This sounds like a lot, but it means the song doesn’t even make the top 85 in terms of number of live performances by the band. This is because they only began performing it in 1987, and the band stopped playing entirely in 1995 upon the death of their lead guitarist and talisman, Jerry Garcia.

The Grateful Dead ended in 1995, but the band has lived on since then in a series of groups. These groups have contained various original members, gradually decreasing in number. The first was The Other Ones, followed by The Dead. But the longest-lived and most successful has been Dead & Company, which today includes two members of the Grateful Dead: Bob Weir, the rhythm guitarist and vocalist, and Mickey Hart, the drummer. It also includes another drummer, Jay Lane, and the bassist Oteil Burbridge and keyboard player Jeff Chimenti. Finally, there’s John Mayer on lead guitar and vocals.

On a fortunately-timed business trip to Las Vegas last month, I saw Dead & Company on a Thursday night and Friday night. This was the last weekend of their second two-month “residency” at the Sphere, the futuristic new music venue that looks as if it simply fell from outer space and landed a block from the Strip, and now blinks out strange messages all day and night.

If they were tired and happy to be nearing the end of this run, they sure didn’t sound like it. Read more »

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

Thanks to Sahitya Raja for the introduction.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Rafaël Newman

Zurich was James Joyce’s home on several occasions. The writer’s first sojourn there, in 1904, was brief: when the prospect of a job teaching English in Switzerland didn’t pan out, he and his partner, Nora Barnacle, freshly arrived from Dublin, soon moved on to Trieste, then still the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s only seaport. Joyce and Nora returned to Zurich in 1915 and spent most of the Great War there, renting apartments in various districts as Joyce worked on Ulysses and took part in the intellectual life of a city teeming with refugees. Finally, having spent the interwar period for the most part in Paris, by 1940 the couple were back in Zurich, where Joyce died the following year. He remains in the city to this day, in Fluntern Cemetery, where his seated memorial gazes out wryly, if myopically, at Lake Zurich and the Alps beyond.

That the Swiss metropolis boasts the Zürich James Joyce Foundation, however, an internationally renowned center for Joyce research and scholarship, is due less to the Irish writer’s tenancy in the city, in life as in death, than it is to the achievements of another man, a Swiss native and Zurich local named Fritz Senn, who has devoted much of his long life to the study and promotion of Joyce’s work. Among Senn’s many publications are Joyce’s dislocutions: Essays on reading as translation (1984); Nicht nur Nichts gegen Joyce. Aufsätze über Joyce und die Welt (1999); Joycean Murmoirs (2007); and, most recently, Ulysses Polytropos (2022). Senn has founded and edited international journals, initiated Joyce symposia, and, together with Klaus Reichert, compiled the Frankfurt James Joyce Edition, in seven volumes.

The Zürich James Joyce Foundation (ZJJF), which celebrates its 40th birthday this year, was established in 1985 with financial assistance from the Schweizerischer Bankverein (today’s UBS) to house Fritz Senn’s collection of first editions, secondary literature, and Joycean memorabilia, and to allow visiting scholars to profit from Senn’s personal expertise along with the library and archive. The ZJJF holds open reading groups, typically led by Senn himself, in which participants read Ulysses and Finnegans Wake together over the course of many months, and organizes a series of talks, known as the Strauhof Lectures, by noted Joyce specialists. It hosts a translators’ roundtable and regularly stages convivial celebrations of Joyce’s work, with readings and music at Christmas and, of course, a yearly Bloomsday event every June 16, commemorating Joyce and Nora’s first assignation and the date on which Ulysses is set. Read more »

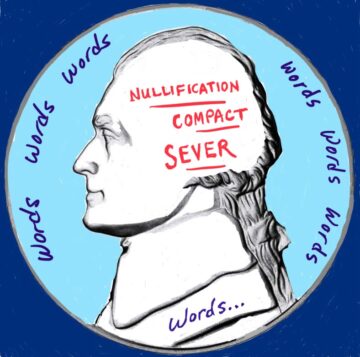

by Michael Liss

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

These words, these good words. They are the building blocks of our civic culture. In a democracy like ours, where we do not demand conformity, but rather abide by rules that are essentially an exchange of promises, words are paramount. What do they mean, how binding are they, do they express an unbreakable eternal truth, or do they grow sclerotic, even obsolete? If so, how do we change them? Is there an essence, a central truth that is and must be immutable?

To get any of those answers, we should begin with Jefferson, the central designer and primary wordsmith in the architecture of independence.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Wonderful, isn’t it? Thrilling. It is our intellectual origin story. It should fill us with pride—that, for these principles, we took on the most powerful nation on Earth and, after years of reversals, won. Soon we will celebrate the 249th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. We can trot out some nerdy historian to point out that maybe it’s not really the 4th of July—maybe it’s the 2nd or 3rd. We can indulge ourselves in cautionary reminders how perhaps we haven’t lived up to the promises that are in the Declaration. We can certainly bewail the state of contemporary politics. Or we can just enjoy it, maybe go to a small town if we don’t live in one, see the old cars and the pride of the older soldiers, the flags and bunting, the picnics, the fireworks, the tradition of a 4th of July speech by some local worthy.

Blather—of course it is. Like everything else, we commoditize it, commercialize it, invariably bury the lead: At its best, Independence Day should be a reaffirmation of the Declaration’s central promise. Read more »

……………. All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arm

— Shakespeare, As You Like it, Act II

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Ed Simon

Alternating with my close reading column, every even numbered month will feature some of the novels that I’ve most recently read, including upcoming titles.

A novel, like a symphony, must be conveyed through a particular artistry of time. Unlike a painting, or even a short lyric poem which gestures towards narrative, a novel must dwell in it. Even a novel where “nothing happens” must by the nature of the form make its art happen through the progression of a past into the future, but it in the complexities of that transition – the roundabouts, the flashbacks, the shifting, the slip-streaming, the ruminations, and the foreshadowing – which makes extended prose so adept at conveying the ambiguous feeling of time itself. Within a novel, time can be treated as anything but simple, so that the past can find itself perennial; the future can be a matter of precognition; the present an eternity (or, conversely, nothing at all). “Where there is no passage of time there is also no moment of time, in the full and most essential meaning of the word,” writes the Russian Formalist critic Mikhail Bakhtin in his The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. “If taken outside its relationship to past and future, the present loses its integrity, breaks down into isolated phenomena and objects, making of them a mere abstract conglomeration.” The abstraction of the present is what some mediums exult at – whether lyric or painting – but a novel can’t help but exist amidst the texture of time, its warp and warble, its nicks and snares.

The Spoiled Heart by British novelist Sunjeev Sahota masterfully interrogates time, in particular time’s daughter of memory and its cruel son trauma. Published in April, Sohata’s novel is set in industrial Chesterfield, a small hamlet in Derbyshire. Focalized around the local union leader Nayan Olak, though narrated by his occasional childhood friend Sajjan Dhanoa who is equal parts roman a clef and Nick Carraway, The Spoiled Heart is set in a realistic England distant from many Americans’ country house fantasies. Working-class and multicultural, tough and often despairing, this is the England not necessarily of Blenheim and Wentworth Woodhouse, or even of red phone-booths, double-decker buses, and fish and chips, but rather of kebab houses and labor politics, strikes and stark class divisions. Nayan, the son of Indian Sikh immigrants, suffered hideous trauma twenty years before, when as a young man barely into his 20s a seemingly accidental fire in his parent’s High Street shop killed his mother and young son. The tragedy destroys Nayan’s marriage so that in between caring for his bitter and demented father, he ultimately dedicates his life to Unify, a union representing laborers across a variety of industries. Having decided to run for the presidency of Unify, Nayan is challenged by his colleague and former friend Megha Sharma. Where Nayan is a class-essentialist leftist of the Corbynite variety, Sharma – also the daughter of Indian immigrants, albeit from a well-heeled class – is an adherent to an identity-focused liberalism. Much of the drama from The Spoiled Heart derives from the ideological and personal friction between these two.

But were Sahota’s novel only a means of allegorizing post-Brexit and post-covid fissures in the British left it wouldn’t be nearly as fascinating, and moving, as it is. Read more »

by Chris Horner

What does it mean to live a Good Life in the secular west? Good can mean more than one thing, of course: apart from moral good – doing the right or ‘good’ thing, there is the idea of ‘good’ as flourishing, being happy, fulfilled. The latter matters to us a lot, judging by all the self-help books, YouTube influencers, Rules for Life and so on. For very many lucky enough not to have to worry about poverty or war there still seems a grinding anxiety about how to achieve a happy life. That life seems to be Elsewhere. But why? Some would argue that the angst is due a loss of a shared way of life, one grounded in a conception of human purpose. So, we get nihilism and sense of anomie. Yet lost wallets are returned, and courtesy is still exhibited in everyday situations. If this is moral anarchy, it is not as chaotic as one might expect. Nevertheless. I think something has changed for moderns.

With the decline of an Authority often associated with the Christian church in the West, many people experience the question of what one should do as a burden. As an unlamented Paternal Authority wanes, anxiety about happiness and fulfilment takes its place. The new Superego command is to enjoy oneself, be the best one can be, stay fit, be loved, and be attractive. Consequently, we turn to an army of experts and coaches eager to provide us with ‘rules for living’. And the appetite for moral judgment hasn’t left us either: yet more rules about what one ought to say or not say (rather than action that might change anything).

Modernity—however we define it—follows the Enlightenment. Kant described Enlightenment as the end of tutelage and the accession to maturity, with the responsibilities that come with freedom. Freedom is understood as the end of the tyranny of princes and prelates, the chance to fulfil one’s desires. However, greater knowledge of the self leads to greater doubts about those desires, and the causes of Desire itself. The autonomy promised by Enlightenment seems compromised from the start. While Nietzsche, along with Freud, is regularly cited as the key figure in this creeping sense that the subject isn’t master in their own house, Hegel foreshadows both. For Hegel, too, there are no simple, undivided identities: we are divided subjects. Read more »

by Claire Chambers

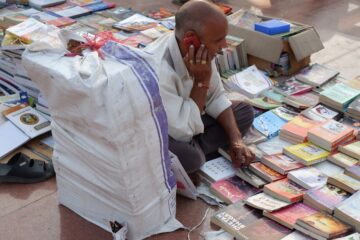

Entering Delhi’s famous Sunday Book Market – known locally as the Patri Kitab Bazaar – in Daryaganj is to step into another world. Previously a tangle of tarpaulin stalls behind Jama Masjid, it has been moved to a gated compound called Mahila Haat. In her new Cambridge University Press Element titled Old Delhi’s Parallel Book Bazaar, Kanupriya Dhingra treats this market as an improvisatory ‘location for books and a site of resilience and possibilities’.

Dhingra, a South Asia print historian who earned her PhD at SOAS (University of London) and now works as a professor at BML Munjal University, passed much of her life as a young adult among these booksellers. In our interview she explained that her middle-class family had not given her a particularly bookish childhood. Yet, as a student searching for texts to ‘help with passing exams’ and then as a researcher, she was unexpectedly introduced to the neglected but fascinating subject of parallel book bazaars. Over years of fieldwork, she came to realize that these markets encapsulate Delhi’s historical, economic, and socio-political currents. The result is a 92-page minigraph that fuses memoir, reportage, and analysis to tell the bazaar’s story. It reads at once as a colourful ethnographic diary and an invitation to imagine an alternative literary landscape.

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called The Vicious Case of the Viral Vaccine. This scintilla of serendipity – arising from what she calls ‘double chance encounters’ – defines the market. Read more »

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called The Vicious Case of the Viral Vaccine. This scintilla of serendipity – arising from what she calls ‘double chance encounters’ – defines the market. Read more »

by Christopher Hall

When J. L. Austin published his book How to do Things With Words, his intent was to demonstrate that language must be understood to go beyond any mere reference function. We do not use language merely to point to things in the world, but also to enact things within the world. “I christen thee the Titanic” is a linguistic act. The non-referential quality of language ought to be of some concern to us at the moment. Trump, bullshitter supreme, has never cared about the referential aspect of his language, and whether that bears any correspondence with reality. What strikes me most about Trump’s 2nd term is that he seems to be deploying this empty language with intent; MAGA has become self-aware, perhaps even sentient. The key to the Trump presidency is not misinformation, but the ultimate distrust of information itself. He wants, and is getting, a people who can be convinced to distrust all signals, and thus hear only noise. Everything Trump says is designed to enact something on the listener; what Trump is actually talking about is often irrelevant.

There is a clumsy will-to-power here, but Trump’s fundamental authoritarian impulse doesn’t, for the moment, seem to be pulling in the typical direction. Of course, it’s entirely possible that he wants people to believe that Haitians are eating pets in Springfield, or that there’s a white genocide occurring in South Africa. But there’s also a very real sense that he simply doesn’t care. Orwell envisioned political language as being rendered “dead,” particularly (but not exclusively by any means) in authoritarian states. And yes, Trump’s limited vocabulary, his absurd repetitions and locutions, and his general bumptious cadence, might all be symptoms of general necrosis. But, at least in this sphere, Trump doesn’t have to coerce anybody. It’s enough to present nonsense and proclaim that people can think what they want.

The politician as bullshitter is nothing new. But as I think about Trump and the new authoritarianism’s affect on the public sphere, I am beginning to believe the key to 21st century is not what Orwell saw as a deadening of language. Yes, meaning is on the decline, but it is coming about not as result of repressive restriction, but rather through perverse exuberance. Language isn’t dying; it is experiencing cancerous growth. If it true that authoritarian states like China and Russia continue to enforce silence, they increasingly do not to rely on this alone as a means of control; overwhelming noise will do the trick just as well. Do we understand enough about control by noise to understand this trajectory in our political future? Read more »

by Lei Wang

My mother, who was a doctor, always wished she could have been a teacher instead. She was assigned to be a doctor in 1970s China in the weird way the government assigned people to careers then, based solely on test scores. (My dad, assigned as a programmer, had really wanted to pursue a purer, less applied kind of science.) Mom did like being a doctor, though always warned me against going into medicine: the dangers of knowing too much, also all those turtle shells (what she called organic chemistry compounds) to memorize. Perhaps because she really wanted to be a teacher, perhaps because when she immigrated to America, she could no longer practice medicine, she loved to talk to me enthusiastically about biology, especially about T cells and germs as the cops and robbers of the immune system, as if she were my personal Mrs. Frisbee of the Magic School Bus.

I have not gone into medicine, but I have taken weird, pseudoscientific healing classes that may very well be related to growing up with too many biology metaphors. Recently, I have been thinking: we call it healing, but for whom? When healing a cold, aren’t we actually just mass-murdering viruses? I have a friend who everyone in our friend group agrees is the most loving person we know; during the pandemic, when she got sick yet again, the dark joke was that she was too hospitable to viruses, too accommodating of their comfort. She could have stronger boundaries.

“There are two kinds of people, cancer people and allergy people,” a metaphysical healer once told me. “Cancer people take too much in and allergy people keep too much out.” This made sense, metaphorically. We want to know why, and sometimes the symptoms really do fit the situation (I also like to think, since I have allergies, that this means I will not get cancer). Read more »

by O. Del Fabbro

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.

Putin himself thus sees a continuation between the unipolar world order and the multipolar world order. But Putin also regularly looks back at the world order that was in place before the unipolar world order reigned: bipolarity. Putin is, as we know, the greatest critic of the Soviet Union and of its weakness and collapse. It brought nothing but economic chaos and political anarchy. Putin blames the Soviets to have created Ukraine, they gave the “little brother” its national identity, that today Ukrainians are claiming for themselves. In Putin’s narrative, the unipolar world order has only existed since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and was itself preceded by bipolarity. To sum up: the narratives of unipolar, bipolar and multipolar world orders are connected, and cannot be looked at separately. They are evolutionary linked to one another and represent a historical development.

My claim is that to speak of unipolar, bipolar and multipolar world orders means to think in imperial terms, which neglects the complexities of local and internal struggles, of ideological, religious, political, social, economic and many more dimensions. Read more »

by Kyle Munkittrick

Nearly every argument against longevity is a version of, “But death is good sometimes.” Death creates finitude, thereby creating meaning and forcing change. Take Frances Fukuyama’s recent piece “Against Life Extension” in Persuasion. Fukuyama argues slower generational turnover delays social and political dynamism. He does this at 72, recapitulating an argument from over 20 years ago, without a hint of irony. What is odd is that Fukuyama, like others who oppose life extension because it robs us of finitude, doesn’t explore any other source of finitude beyond one: death.

Here is Fukuyama’s claim:

The slowing of generational turnover is thus very likely to slow the rate of social evolution and adaptation, in line with the old joke that the field of economics advances one funeral at a time. […] You will have an overlapping of generations and increasing social conflict as younger people begin to think differently and demand change, while older ones resist. The problem will not be conflict per se, but a gradual slowing of the rate of social change.

Fukuyama opens by pointing out out that life expectancy has gotten longer and that’s good. His first implicit claim, that as people live longer society itself gets older, is, I suspect, so self-evident in government and in our movies, that he doesn’t feel the need to note it. But by not pointing out that our society is already older, he doesn’t have to address the fact that it’s not entirely obvious our society is also already less dynamic. It is almost a truism that we live in a world of accelerating change, not just in tech, but politics and social movements. If we accept the claim that we’re already older, our society should already be getting slower, right? Read more »

by Azadeh Amirsadri

Mom, what was it like for you to hand your one-year-old to your mother-in-law and father-in-law, and leave the continent for what turned out to be an 18-month stay in a country where you didn’t speak the language? Your husband was in school all day, learning French and studying for his degree, and you were home alone with your 3 and a half -year-old and pregnant with your next baby. You said you would look out the window and just cry some days because you felt so lonely when he was out. Did your toddler see your tears and hear your voice cracking as you were feeding her, rocking her, and playing with her? Once your baby was born, how did you manage to take care of your tiny children without your own family around, without speaking French fluently yet, and with a hole in your heart? You said there was a particular song that reminded you of me, a song about someone with a delicate, crystal-like neck. Another song, Tak Derakhti (Lone Tree) by Pouran, was your sad song and described your feelings.

Mom, what was it like coming back home, after a long 18 months, with your two children, and I didn’t even know you? How quickly did you try to take me home to stay with you? I remember staying overnight at times with you and my sisters, and dad who was always busy reading a newspaper or writing. I was just spending the night with you all and would eventually go back to the comfort of my home with my grandparents, where the smells were familiar, and the sounds were quieter. I would go back to sleeping on the floor mattress with my grandmother, playing with her hair and mine, intertwining them into a big knot until I fell asleep. Her breath smelled like hot tea, and it was sweet and warm. I was super spoiled and loved by them, and that was my real home.

Mom, do you remember when your fourth child was born? She was a big, round, beautiful baby, and I came with my grandmother to visit you. You had all your cousins there, and they had brought flowers, mostly tall gladiola, and a lot of sweets, and you were all speaking in your own dialect. I didn’t understand it then, but oh how I miss hearing it now that you are all gone. My sisters and I were interested in the new baby and the sweets. Read more »

A plastic ring about 4 inches in diameter that I saw on the ground in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol. No idea what it is. I just report these important facts. Make of them what you will.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Tim Sommers

Most of the evidence available to us suggests that there is something.

There are probably electrons and other fundamental particles, as well as fields and fundamental forces, likely there are planets, stars, black holes, and galaxies, and there are probably even, what Quine called, “medium-sized” objects: tables, chairs, dogs, and us.

As far as I understand it, however, there is nothing that we know of that couldn’t not exist or go out of existence – including electrons. Although, an electron’s lifespan is long – something like 66,000 yottayears. (I know, I know yottayears sound made up, but it’s 1028 years.) This is a much longer life span than the life span of the universe itself – which won’t extend to more than 100 trillion years or so.

Anyway, if every single thing could not exist, then everything could not exist all at once, and so there would and could be nothing. And if there could be nothing, why isn’t there nothing? Existing is more complicated – and energy intensive – than not existing, so, it would seem that the universe would tend towards nothing.

On the other hand, when I said that the lifetime of the universe, though long, is finite, I was following cosmologists who don’t really mean that the universe will literally go out of existence eventually. They mean that the universe will undergo heat death.

Everything interesting thing about the universe – including life and information – is a result of energy gradients. They cool your coffee, make your computer compute, and create waterfalls. Energy gradients make stuff happen.

Energy gradients exist wherever two points sufficiently proximate to one another have different levels of energy, causing the energy to flow from the more energetic point to the less energetic point. Energy gradients, in action, eliminate themselves by spreading their energy out more evenly. Entropy is the measure of this process. Energy gradients push the universe towards a state where everything is distributed uniformly and nothing interesting can ever happen again. Heat death.

However, the point is that heat death is not itself, literally, the end of the universe. Nevertheless, if the fundamental particles have finite life-spans, no matter how long, the universe as a whole will eventually experience heat death and then, some time later, go out of existence entirely.*

Nothing is coming. And nothing can come from nothing. As Heidegger put it, “The Nothing Nothings.” So, once there is nothing, the conventional wisdom goes, there can’t ever be anything again. Read more »

by Priya Malhotra

When I typically envisioned a woman in her seventies, I—like many of us—pictured someone wrinkled and bent—not just physically, but also mentally and emotionally. I imagined someone dimmed, only to fade further with time. A woman well past the best years of her life, wearied by disappointments, melancholy with regrets for cherished things that never came to fruition, and weighed down by the realization that those longings would likely never be fulfilled. She was someone who tucked those yearnings away, lest they resurface as reminders of everything she had lost. Old age, I believed, was a time of decline—the deterioration of one’s faculties, the shedding of one’s dreams, a slow march toward the inevitable.

But then I moved to India and witnessed how my cousin Rashmi (name changed for privacy) lived—and aged—and every depressing notion I had about growing old was upended.

At 71, Rashmi radiates a resplendent glow that’s nothing short of infectious. Her hair is fully grey and she wears it with grace. Her skin bears the spots and textures of age, her body sags in places—but her spirit sings. The way she moves through life with joy and poise is more inspiring than I can describe.

“Aging is a gift,” she tells me. “So many people don’t get to that point. It’s not afforded to everybody. Aging can be great—but there’s a caveat. You need to be in good health.”

It’s not Botox or anti-aging creams that keep her youthful. It’s her innate, almost childlike sense of wonder. And like a child, she delights in the infinite delights of the world. She’ll bubble with enthusiasm over intricately embroidered linen table mats or latticework crafted in a dusty Delhi storefront. She’s equally enraptured by the grandeur of a centuries-old dome or a Caravaggio masterpiece. In her eyes, the world is even more magical now than it was thirty years ago.

“Then, I took it all for granted,” she says. “Now I don’t. Youth gives you a sense of immortality—you think you’ll always have time to enjoy life’s enchantments. But as you get older, there’s this wonderful urgency to enjoy them now.” Read more »

by David Beer

Could there be anything more insulting for a writer than someone assuming that their writing is an output of generative artificial intelligence? The mere possibility of being confused for a neural network is enough to make any creative shudder. When it happens, and it will happen, it will inevitably sting.

By implication, being mistaken for AI is to be told that your writing is so basic, so predictable, so formulaic, so replicable, so obvious, so neat, so staid, so emotionless, so stylised, so unsupervised, that it is indistinguishable from the writing of a replication machine. Your writing, such a slur will tell you, lacks enough humanity for it to be thought of as being human. The last thing any writer needed was another possible put-down for their work.

Over a decade ago, in the 2012 book How We Think, Katherine Hayles’ concluded that being immersed within and operating alongside advancing networked media structures, with changing cognitive abilities, changes thinking itself. This shift in how we think inevitably has implications for how we write too. Beyond this, there is a new pressure now. As we interface with it, AI will not just directly change what and how we know, but will also impact on how we anticipate being judged in comparison to those generative systems.

With the fear of the insult and the anxiety of comparison in the background, the objective of writing may be to avoid the threat of someone wondering, if only for a moment, if you had simply typed a prompt into your preferred app and then comfortably reclined to stream a TV show. Will we now push ourselves to write in a style that means we can’t possibly be confused for AI? Might we try to sound more human, more distinct, more fleshy, and therefore less algorithmic. As we adapt our writing in response to the presence of AI, we will enter into a version of what Rosie DuBrin and Ashley Gorham have called ‘algorithmic interpellation’. That is to say that when we are incorporated into algorithmic structures, even acts of resistance are defined and directed by those very circumstances. What AI writing looks like will become the thing to avoid replicating, meaning that the form AI takes will also define attempts at its opposition. Read more »