by Christopher Hall

When this article is published, it will be close to – perhaps on – the 39th anniversary of one of the most audacious moments in television history: Bobby Ewing’s return to Dallas. The character, played by Patrick Duffy, had been a popular foil for his evil brother JR, played by Larry Hagman on the primetime soap, but Duffy’s seven-year contract with the show had expired, and he wanted out. His character had been given a heroic death at the end of the eighth season, and that seemed to be that. But ratings for the ninth season slipped, Duffy wanted back in, and death in television, being merely a displaced name for an episodic predicament, is subject to narrative salves. So, on May 16, 1986, Bobby would return, not as a hidden twin or a stranger of certain odd resemblance, but as Bobby himself; his wife, Pam, awakes in bed, hears a noise in the bathroom and investigates, and upon opening the shower door, reveals Bobby alive and well. She had in fact dreamed the death, and, indeed, the entirety of the ninth season.

When this article is published, it will be close to – perhaps on – the 39th anniversary of one of the most audacious moments in television history: Bobby Ewing’s return to Dallas. The character, played by Patrick Duffy, had been a popular foil for his evil brother JR, played by Larry Hagman on the primetime soap, but Duffy’s seven-year contract with the show had expired, and he wanted out. His character had been given a heroic death at the end of the eighth season, and that seemed to be that. But ratings for the ninth season slipped, Duffy wanted back in, and death in television, being merely a displaced name for an episodic predicament, is subject to narrative salves. So, on May 16, 1986, Bobby would return, not as a hidden twin or a stranger of certain odd resemblance, but as Bobby himself; his wife, Pam, awakes in bed, hears a noise in the bathroom and investigates, and upon opening the shower door, reveals Bobby alive and well. She had in fact dreamed the death, and, indeed, the entirety of the ninth season.

This imposition on the audience’s credibility (though rarely done with such chutzpah) has occurred often enough in television and other media (comic books in particular, which is where the term originated) to have earned a name: retroactive continuity. Continuity refers to our sense that events should proceed in logical sequence, but the retroactive element insists that a key and unexpected change has occurred which alters or nullifies some previous sequence. Something deeply out of expected continuity has happened in the narrative, which means that our interpretation of previous events must be completely changed, or, in this case, obliterated. You watched season nine, but it didn’t happen. Schrodinger’s Bobby Ewing: we saw him die, worked through the consequences of that for a season of television, and yet here he is lathering up in the shower.

Retroactive continuity – or retcon, retconning – is a kludge, an act of “repair” done to a narrative to ease the consequences of what is usually some external, often commercial, pressure. Its literate cousin is peripeteia, the moment of sudden reversal, the turning point, the more specific version of which is anagnorisis, the recognition, the new knowledge that changes our understanding of everything. The archetypical example of this is in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, when the terrible knowledge that he is the father-killing, mother-schtupping abomination causing the plague in his city dawns on the title character.

What happened to Bobby Ewing in Dallas was clumsy to the point of loutishness, and the worst thing about it was what it implied about the audience: that it might roll its eyes, but there was a reasonable certainty it would keep right on watching. (The series lasted another 5 years after Bobby’s return.) The moment of anagnorisis in Oedipus Rex is, in contrast, narrative perfection; the story could end no other way. (It no doubt helped, of course, that the Greek audience already knew the ending.) Read more »

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing.

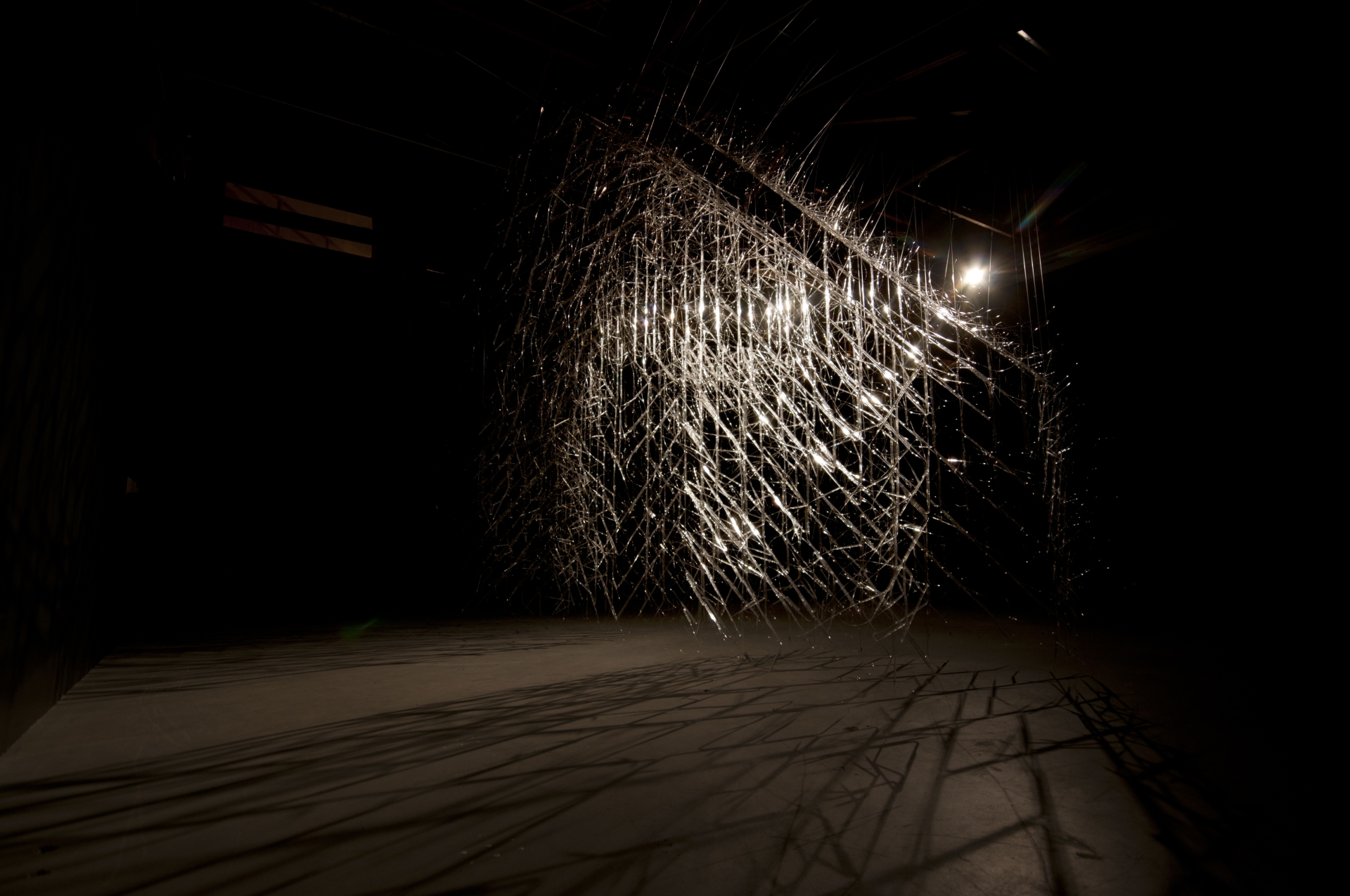

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing. Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.

Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions.

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions. In my Philosophy 102 section this semester, midterms were particularly easy to grade because twenty seven of the thirty students handed in slight variants of the same exact answers which were, as I easily verified, descendants of ur-essays generated by ChatGPT. I had gone to great pains in class to distinguish an explication (determining category membership based on a thing’s properties, that is, what it is) from a functional analysis (determining category membership based on a thing’s use, that is, what it does). It was not a distinction their preferred large language model considered and as such when asked to develop an explication of “shoe,” I received the same flawed answer from ninety percent of them. Pointing out this error, half of the faces showed shame and the other half annoyance that I would deprive them of their usual means of “writing” essays.

In my Philosophy 102 section this semester, midterms were particularly easy to grade because twenty seven of the thirty students handed in slight variants of the same exact answers which were, as I easily verified, descendants of ur-essays generated by ChatGPT. I had gone to great pains in class to distinguish an explication (determining category membership based on a thing’s properties, that is, what it is) from a functional analysis (determining category membership based on a thing’s use, that is, what it does). It was not a distinction their preferred large language model considered and as such when asked to develop an explication of “shoe,” I received the same flawed answer from ninety percent of them. Pointing out this error, half of the faces showed shame and the other half annoyance that I would deprive them of their usual means of “writing” essays.

s on a common topic. Yet at noon on May 8th, all 16 high school seniors in my AP Lit class were transfixed by one event: on the other side of the Atlantic, white smoke had come out of a chimney in the Sistine Chapel. “There’s a new pope” was the talk of the day, and phone screens that usually displayed Instagram feeds now showed live video of the Piazza San Pietro in Rome.

s on a common topic. Yet at noon on May 8th, all 16 high school seniors in my AP Lit class were transfixed by one event: on the other side of the Atlantic, white smoke had come out of a chimney in the Sistine Chapel. “There’s a new pope” was the talk of the day, and phone screens that usually displayed Instagram feeds now showed live video of the Piazza San Pietro in Rome.

Danish author Solvej Balle’s novel On the Calculation of Volume, the first book translated from a series of five, could be thought of as time loop realism, if such a thing is imaginable. Tara Selter is trapped, alone, in a looping 18th of November. Each morning simply brings yesterday again. Tara turns to her pen, tracking the loops in a journal. Hinting at how the messiness of life can take form in texts, the passages Tara scribbles in her notebooks remain despite the restarts. She can’t explain why this is, but it allows her to build a diary despite time standing still. The capability of writing to curb the boredom and capture lost moments brings some comfort.

Danish author Solvej Balle’s novel On the Calculation of Volume, the first book translated from a series of five, could be thought of as time loop realism, if such a thing is imaginable. Tara Selter is trapped, alone, in a looping 18th of November. Each morning simply brings yesterday again. Tara turns to her pen, tracking the loops in a journal. Hinting at how the messiness of life can take form in texts, the passages Tara scribbles in her notebooks remain despite the restarts. She can’t explain why this is, but it allows her to build a diary despite time standing still. The capability of writing to curb the boredom and capture lost moments brings some comfort.

Many have talked about Trump’s war on the rule of law. No president in American history, not even Nixon, has engaged in such overt warfare on the rule of law. He attacks judges, issues executive orders that are facially unlawful, coyly defies court orders, humiliates and subjugates big law firms to his will, and weaponizes law enforcement to target those who seek to uphold the law.

Many have talked about Trump’s war on the rule of law. No president in American history, not even Nixon, has engaged in such overt warfare on the rule of law. He attacks judges, issues executive orders that are facially unlawful, coyly defies court orders, humiliates and subjugates big law firms to his will, and weaponizes law enforcement to target those who seek to uphold the law. When this article is published, it will be close to – perhaps on – the 39th anniversary of one of the most audacious moments in television history: Bobby Ewing’s return to Dallas. The character, played by Patrick Duffy, had been a popular foil for his evil brother JR, played by Larry Hagman on the primetime soap, but Duffy’s seven-year contract with the show had expired, and he wanted out. His character had been given a heroic death at the end of the eighth season, and that seemed to be that. But ratings for the ninth season slipped, Duffy wanted back in, and death in television, being merely a displaced name for an episodic predicament, is subject to narrative salves. So, on May 16, 1986, Bobby would return, not as a hidden twin or a stranger of certain odd resemblance, but as Bobby himself; his wife, Pam, awakes in bed, hears a noise in the bathroom and investigates, and upon opening the shower door, reveals Bobby alive and well. She had in fact dreamed the death, and, indeed, the entirety of the ninth season.

When this article is published, it will be close to – perhaps on – the 39th anniversary of one of the most audacious moments in television history: Bobby Ewing’s return to Dallas. The character, played by Patrick Duffy, had been a popular foil for his evil brother JR, played by Larry Hagman on the primetime soap, but Duffy’s seven-year contract with the show had expired, and he wanted out. His character had been given a heroic death at the end of the eighth season, and that seemed to be that. But ratings for the ninth season slipped, Duffy wanted back in, and death in television, being merely a displaced name for an episodic predicament, is subject to narrative salves. So, on May 16, 1986, Bobby would return, not as a hidden twin or a stranger of certain odd resemblance, but as Bobby himself; his wife, Pam, awakes in bed, hears a noise in the bathroom and investigates, and upon opening the shower door, reveals Bobby alive and well. She had in fact dreamed the death, and, indeed, the entirety of the ninth season.