by Charles Siegel

Oh the streets of Rome

are filled with rubble

Ancient footprints are everywhere

You can almost think

that you’re seeing double

On a cold, dark night

on the Spanish Stairs

Those are the first lines of “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” a song written by Bob Dylan in 1971. I remember that the first time I heard the tune, I thought it was by The Band, because they actually released it first in September of 1971. Two months later, Dylan’s version came out, oddly enough on the album “Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. II.”

Many artists have covered the song, most notably the Grateful Dead. They played it 144 times, according to gratefulsets.net. This sounds like a lot, but it means the song doesn’t even make the top 85 in terms of number of live performances by the band. This is because they only began performing it in 1987, and the band stopped playing entirely in 1995 upon the death of their lead guitarist and talisman, Jerry Garcia.

The Grateful Dead ended in 1995, but the band has lived on since then in a series of groups. These groups have contained various original members, gradually decreasing in number. The first was The Other Ones, followed by The Dead. But the longest-lived and most successful has been Dead & Company, which today includes two members of the Grateful Dead: Bob Weir, the rhythm guitarist and vocalist, and Mickey Hart, the drummer. It also includes another drummer, Jay Lane, and the bassist Oteil Burbridge and keyboard player Jeff Chimenti. Finally, there’s John Mayer on lead guitar and vocals.

On a fortunately-timed business trip to Las Vegas last month, I saw Dead & Company on a Thursday night and Friday night. This was the last weekend of their second two-month “residency” at the Sphere, the futuristic new music venue that looks as if it simply fell from outer space and landed a block from the Strip, and now blinks out strange messages all day and night.

If they were tired and happy to be nearing the end of this run, they sure didn’t sound like it. Read more »

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

Nirmal Raja. Entangled / The Weight of Our Past, 2022.

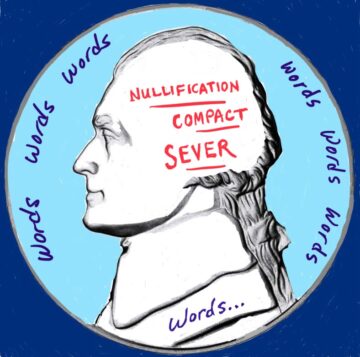

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

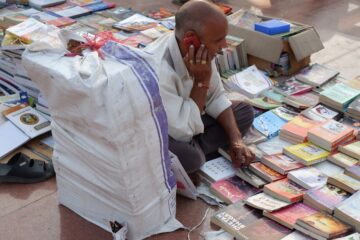

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.

One argument for the existence of a creator /designer of the universe that is popular in public and academic circles is the fine-tuning argument. It is argued that if one or more of nature’s physical constants as mathematically accounted for in subatomic physics had varied just by an infinitesimal amount, life would not exist in the universe. Some claim, for example, with an infinitesimal difference in certain physical constants the Big Bang would have collapsed upon itself before life could form or elements like carbon essential for life would never have formed. The specific settings that make life possible seem to be set to almost incomprehensible infinitesimal precision. It would be incredibly lucky to have these settings be the result of pure chance. The best explanation for life is not physics alone but the existence of a creator/designer who intentionally fine-tuned physical laws and fundamental constants of physics to make life physically possible in the universe. In other words, the best explanation for the existence of life in general and ourselves in particular, is not chance but a theistic version of a designer of the universe.

One argument for the existence of a creator /designer of the universe that is popular in public and academic circles is the fine-tuning argument. It is argued that if one or more of nature’s physical constants as mathematically accounted for in subatomic physics had varied just by an infinitesimal amount, life would not exist in the universe. Some claim, for example, with an infinitesimal difference in certain physical constants the Big Bang would have collapsed upon itself before life could form or elements like carbon essential for life would never have formed. The specific settings that make life possible seem to be set to almost incomprehensible infinitesimal precision. It would be incredibly lucky to have these settings be the result of pure chance. The best explanation for life is not physics alone but the existence of a creator/designer who intentionally fine-tuned physical laws and fundamental constants of physics to make life physically possible in the universe. In other words, the best explanation for the existence of life in general and ourselves in particular, is not chance but a theistic version of a designer of the universe. Sughra Raza. Scattered Color. Italy, 2012.

Sughra Raza. Scattered Color. Italy, 2012.