by Philip Graham

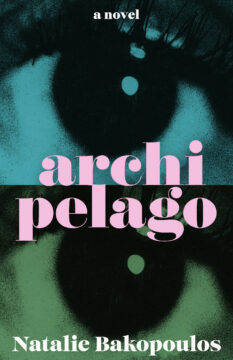

Archipelago, the third novel by Natalie Bakopoulos, ranges among the Cycladic Islands of Greece, the coast of Croatia, and crosses the borders of various Balkan states until finally—temporarily?—settling in a small town in the Peloponesian peninsula. All this traveling echoes (and is echoed by) the inner journey of the unnamed (and yet named) narrator of Archipelago, a translator who, as the novel progresses, seems to allow her own self to be written, to be translated.

Archipelago, the third novel by Natalie Bakopoulos, ranges among the Cycladic Islands of Greece, the coast of Croatia, and crosses the borders of various Balkan states until finally—temporarily?—settling in a small town in the Peloponesian peninsula. All this traveling echoes (and is echoed by) the inner journey of the unnamed (and yet named) narrator of Archipelago, a translator who, as the novel progresses, seems to allow her own self to be written, to be translated.

Archipelago is a heady read, deceptively quiet and yet rife with private risk-taking and minute transgressions. It’s a novel that sets its own pace and sets its own rules as the narrator, in the process of discovering herself, must also learn how to remember herself.

*

Philip Graham: I have so much to say and ask about this beautifully-written house of mirrors that is Archipelago, your latest novel, that I don’t know where best to start. Perhaps the novel’s own beginning? The narrator, a translator of Greek literature on her way to a literary conference, has a brief but disturbing encounter with an aggressive man. A case of mistaken identity? She has no recollection of this man, but somehow she has become a character in his angry imagination. The possibility of being a “someone else,” seems to cling to her in different ways as the novel progresses.

Meanwhile, she decides to forego reading a novel—titled Occupation—before beginning to translate it, a new professional process for her. “I wanted to try translating something as I was coming to know it,” she says, in order to “tell a story before I knew its ending.” Her translating “blind” sets the stage for another thread in the novel, an acceptance of “unknowing” how her own story will move forward.

As she notes near the end of Archipelago, “the beginning is often many places at once.”

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Joan Silber, in The Art of Time in Fiction, writes: “A story is already over before we hear it. That is how the teller knows what it means.” I really appreciate this sentiment, and I even echo it in the book, but I also think the actual telling of the story helps the teller to understand it, and that each telling, or translation, might privilege different things. I fact, I might say that in Archipelago, her narration is as much the story as any other elements of the work. Read more »

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

In recent years chatbots powered by large language models have been slowing moving to the pulpit. Tools like

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

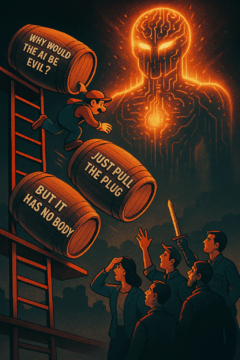

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.