by Tim Sommers

The ends don’t justify the means. Right? But then what does?

Utilitarians say that, of course, the ends justify the means. If the ends can’t justify the means, then nothing can. Utilitarianism is built on the twin pillars of welfarism and consequentialism.

Consequentialism is the view that the morally right thing to do is whatever has the best consequences.

Welfarism is the view that the only thing intrinsically valuable is human happiness, welfare, well-being, having their desires fulfilled, flourishing, or the like.

Utilitarianism calls whatever it is exactly that matters in terms of human good (happiness, having your preferences fulfilled and flourishing are not exactly the same thing) utility. Utility is a technical term for whatever it is that is intrinsically valuable – which has something to do with human happiness

Powerful intuitions support this combination of consequentialism and welfarism. From a consequentialist perspective, to deny the truth of utilitarianism is to be forced to defend the claim that sometimes, given the choice, we should find the worse morally superior to the better. Specifically, that we should sometimes do the thing that has worse consequences – even when we could have done something with better consequences. From the welfarist perspective, to deny utilitarianism is to be forced to defend the claim that we must, at least sometimes, intentionally do things that make everyone overall less happy when we could have done something that would have made people overall more happy.

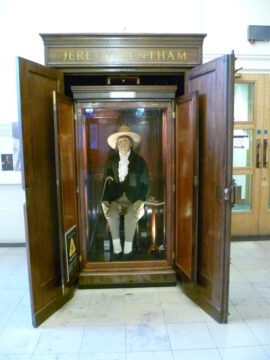

“During much of modern moral philosophy the predominant systematic theory has been some form of utilitarianism,” John Rawls wrote in A Theory of Justice. “One reason for this is that it has been espoused by a long line of brilliant writers who have built up a body of thought truly impressive in its scope and refinement…Hume and Adam Smith, Bentham and Mill, were social theorists and economists of the first rank; and the moral doctrine they worked out was framed to meet the needs of their wider interests.”

However, all the classical utilitarians had in common that they used two very different kinds of argumentative strategies to bolster the view: one we might call the negative or downward approach, the other, the positive or upwards argument. Read more »

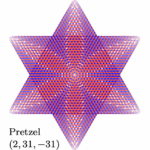

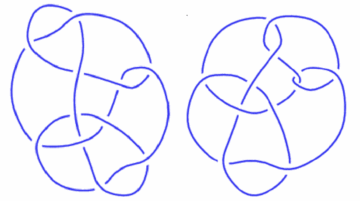

Mathematics is

Mathematics is

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.

The Hanle Dark Sky Reserve is a spectacular spot in Ladakh, in the north of India. It’s surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and at 14000 feet, it’s well above the treeline. So the mountains and the surroundings are utterly barren. Yet that barrenness seems only to enhance the beauty of the Reserve.

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

A bit of information is common knowledge among a group of people if all parties know it, know that the others know it, know that the others know they know it, and so on. It is much more than “mutual knowledge,” which requires only that the parties know a particular bit of information, not that they be aware of others’ knowledge of it. This distinction between mutual and common knowledge has a long philosophical history and has long been well-understood by gossips and inside traders. In modern times the notion of common knowledge has been formalized by David Lewis, Robert Aumann, and others in various ways and its relevance to everyday life has been explored, most recently by Steven Pinker in his book When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows.

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.

Sughra Raza. Departure. December 2024.