by Mark R. DeLong

Rights: Public domain

Restoration of my old car took well more than a decade before it again powered itself along US Highway 501. With time and experience, differences between a craftsman and me would continue to diminish, as my inexperienced hands layered their actions into bodily remembered history and embodied knowledge. My hands remained bumbling and hesitant, though in time a little less than when I began. A craftsman’s hands would be effective and confident, mastering both tools and materials. The craftsman’s eyes, hands, and mind work in concert—far better tuned than mine. But despite the gulf of experience between craftsmanship and my labor, the years hunched over the car opened or, better, finely textured my understanding of how work helps to fulfill human life. That seemingly basic understanding was, paradoxically, obscured by the automobile itself.

A common element that the craftsman and I shared throughout the process amounted to the perspective of the whole project. Even when the car’s parts were contained in Ziplock bags, its chassis stripped to bare metal (much rusted through, too), my mind saw the product that my work, bumbling or not, could bring forth. Mine was an unjustifiably sturdy and very hopeful vision; the same would go for the craftsman, though he had skills to justify the hope. That hopeful perspective, justified and not, formed the strongest bond tying the craftsman and me.

In the mid-nineteenth century, William Morris used hope to draw the distinction between “useful work and useless toil.” “What is the nature of the hope which, when it is present in work, makes it worth doing?” Morris asked in Signs of Change (1888). “It is threefold, I think—hope of rest, hope of product, hope of pleasure in the work itself; and hope of these also in some abundance and of good quality.” Morris along with William Blake and John Ruskin nostalgically revered craft, and Morris particularly romanticized it. Yet, if nostalgia and idealism colored his vision of work somewhat, Morris understood the special qualities of craft work: its connectedness to meaning, its close tie to qualities of uniqueness, beauty, and durability—its reverence for things and the making of them.

Blake’s “dark Satanic Mills” loomed in the factories of the time. The three men yearned for the good old days of craftsmanship as a reaction to the indifferent brutality of the Industrial Revolution, though what they desired—a pleasantly medieval fantasy, really—may never have supplied the needs of their own time.

Over the decades that followed, industry captured Morris’ trinity of hopes—rest, product, and pleasure of work—and weighted them ever more to “product,” eventually leaving behind pleasure of work and, perhaps to an ever-growing extent, rest.

My long, sometimes tedious garage work inched toward some of the outcomes that craftsmen would much more easily achieve. Through it, I glimpsed some of the transformations of thought and action that make up “mastery,” and, importantly, the work I did supported hope and the “pleasure of work” just enough to keep me going on the project. Of course, my view of work would be hopelessly naïve and I’d be as idealistic as William Morris if I believed that craft could fully define “useful work” in my own era. And yet I know that such work nurtures. It fills human experience because it comprehends, in the old sense of the word, the wisdoms of body and of mind. Hand and head work meaningfully, perhaps even most happily, in concord.

* * *

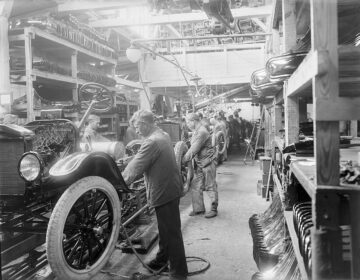

Satisfactions of craftsmanship contrast with work of the machine, which the automobile advanced in the early years of the twentieth century. On its own, the car itself did not bring about the massive shifts in manufacturing in that time, but rather extended inventions and concepts that emerged nearly a century earlier. In the process, car manufacture reoriented notions of useful skills that craftsmen embody, supplanting them with time-bound, bewilderingly repetitious operations of “useless toil,” to use Morris’ perhaps too judgmental phrase. Automobiles carried the banner of modern mass-produced products because they were the most visible and revolutionary things to emerge from the vast machines of factories.

And they were a sight to behold. Henry Ford’s factories became tourist attractions in the early decades of the twentieth century with a half million tourists visiting annually. And yet, conditions of car manufacture also updated Blake’s nineteenth-century “Satanic Mills” for the twentieth-century. Automobile manufacture extended the Industrial Revolution’s transformation of work or, perhaps more accurately, the workplace. The transitional character was Henry Ford whose name expanded into an ideology: Fordism. Its industrial transformation certainly redefined how men and women labored and the skills they needed, but it also shaped their broader roles and responsibilities in society. They became consumers. Fundamental social units such as the family changed as society shifted and reorganized around the new work of mass production.

It wasn’t the case that Ford had no sympathy for craftsmanship. Daniel Boorstin pointed out that “Henry Ford’s faith in the Model T was an Old World faith: a belief in the perfectable product rather than the novel product.” He had an “old-fashioned insistence on craftsmanship and function,” but for Ford, the traditional practices of craftsmanship had aged into “bunk.” Machines and an ever-intensifying twentieth-century efficiency easily surpassed the craftsman. Ford summed it up in his autobiographical My Life and Work (1923): “It is self-evident that a majority of the people in the world are not mentally—even if they are physically—capable of making a good living. That is, they are not capable of furnishing with their own hands a sufficient quantity of the goods which this world needs to be able to exchange their unaided product for the goods which they need.”

Ford had no confidence that the methods of craftsmen could match those of modern manufacture.

“In a little dark shop on a side street an old man had laboured for years making axe handles,” he wrote in what strikes me as uncharacteristically poetic fashion. “Out of seasoned hickory he fashioned them, with the help of a draw shave, a chisel, and a supply of sandpaper. Carefully was each handle weighed and balanced.” The work was long, if not hard, and only modestly productive. “His average product was eight handles a week, for which he received a dollar and a half each. And often some of these were unsaleable—because the balance was not true.”

It is difficult to tell whether Ford pitied the axe-handle maker or even felt a twinge of nostalgia for his work. After all, he had claimed that “history is more or less bunk. . . . We want to live in the present, and the only history that is worth a tinker’s dam is the history we make today.” The axe handle maker was old history, old bunk, however tenderly Ford may have told his story.

“Today you can buy a better axe handle, made by machinery, for a few cents . . . and every one is perfect,” he pointed out. “Modern methods applied in a big way have not only brought the cost of axe handles down to a fraction of their former cost—but they have immensely improved the product.”

In the end, Ford’s achievement was not the Model T. His “unique achievement was less in designing a durable automobile than in organizing newer, cheaper ways to make millions of one kind of automobile,” Boorstin wrote. “He transformed the making of automobiles from a jerky, halting process to a smooth-flowing stream. . . . The factory was no longer a place where a skilled worker put together the many parts of a machine. Now it was where a machine grew on assembly lines that were tended by strategically located men.”

The kind of instruction I got from the repetitions in my garage take on a new meaning in the context of Ford’s factories, where rote “operations” whittled assembly into regimented movement. “Repetitive labour—the doing of one thing over and over again and always the same way—is a terrifying prospect to a certain kind of mind,” Ford admitted. “It is terrifying to me . . . but to other minds, perhaps I might say to the majority of minds, repetitive operations hold no terrors.” Those words open the chapter titled “The Terror of the Machine,” a title that shows Ford clearly saw his manufacturing operations as large-scale machines, their buildings enclosing machinery and tools, closely timed gearing and belts, and tightly orchestrated human “operations” all churning out a product. Such an image of the factory had its origins from the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, when English weavers watched factories rise to displace them with machines and create new and exploitative circumstances for workers.

One man explained work on the line in a feature article published in the Rock Island Tri-City Labor Review in April 1932:

I always think about a visit I once paid to one of Ford’s assembling plants every time any one mentions a Ford car to me. Every employee seemed to be restricted to a well-defined jerk, twist, spasm, or quiver resulting in a fliver.[1] I never thought it possible that human beings could be reduced to such perfect automats.

I looked constantly for the wire or belt concealed about their bodies which kept them in motion with such marvelous clock-like precision. I failed to discover how motive power is transmitted to these people and as it don’t seem reasonable that human beings would willingly consent to being simplified into jerks, I assume that their wives wind them up while asleep.

If the human cost of a “well-defined jerk, twist, spasm, or quiver” was at all clearly visible to twentieth-century consumers, the price nonetheless seemed a fair exchange for the bounty that manufacturers supplied. Productivity in Ford’s factories so profoundly increased that the company produced in a single day in 1925 nearly as many cars as came off the line annually in the first years of the Model T, ensuring that production costs fell dramatically and the cost of the car within range of a large consumer market. Ford’s example of mass manufacture ensured that society’s future would be little like the past. It was to be a future of abundance and a consumer’s democracy.

“Handicrafts, and methods of production that follow the precedent of handicrafts, serve best an aristocracy of consumers, while factories serve best the consumption of a democracy,” wrote historian Victor S. Clark around the time when Ford’s account of his life and work appeared. Clark’s comment related to metal manufacture in New England in the mid-nineteenth century, but his opinion about democracy, aristocracy, and markets fit the spirit of the early twentieth century as well.

The craftsman had lost a central place in the new democratic scheme. He was relegated to serve the aristocracy of consumers and, perhaps, to dogged hobbyists.

[1] A “fliver” was a slang term for a Ford Model T.

For the bibliographically curious: The chapter entitled “Useful Work and Useless Toil” is of interest for the topic of this article, but “Feudal England” shows a bit of Morris’ appreciation for the Middle Ages. “That time was in a sense brilliant and progressive, and the life of the worker in it was better than it ever had been, and might compare with advantage with what it became in after periods and with what it is now; and indeed, looking back upon it, there are some minds and some moods that cannot help regretting it, and are not particularly scared by the idea of its violence and its lack of accurate knowledge of scientific detail.” Morris was probably among them. Morris, William. Signs of Change: Seven Lectures Delivered on Various Occasions. London, New York, Bombay: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1903. https://archive.org/details/signschangeseve00morrgoog/page/n10/mode/2up. Ford produced the book “in collaboration with Henry Crowther,” which may have meant the Henry Crowther handled the pen more than his boss did. It is surprisingly frank about Ford’s unapologetically ruthless labor process and management. Ford, Henry. My Life and Work. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1923. http://archive.org/details/mylifeandwork00crowgoog. Clark particularly examines the development of small metal-working manufacturers in New England, outlining the foundational elements of later large-scale factories. Clark, Victor S. History of Manufactures in the United States, Volume I: 1607-1860. 1929 ed. Vol. 1. 2 vols. New York, London: Carnegie Institution of Washington by the McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1929. https://archive.org/details/historyofmanufac0001vict/mode/2up. Ewen’s book opened up critical history of consumerism in the U.S., and tied it with social transformations engendered by mass production in the twentieth century. Ewen, Stuart. Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of the Consumer Culture. New York, St. Louis, San Francisco: MacGraw-Hill, 1977. Boorstin is just a joyful historian. Boorstin, Daniel J. The Americans: The Democratic Experience. New York: Random House, 1973.

This article is based on a chapter from a book project of mine that examines the car, art, and culture, especially in the United States. The narrative uses a years-long car restoration as a springboard. A previous post considers a meaning of craftsmanship in light of “embodied knowledge.”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.