“The best evidence we have suggests that early Earth was completely covered by oceans, but to link two amino acids together to make a protein, you have to remove water.” And that would have been impossible if the amino acids were immersed in an ocean. Life needed some land—literally a beachhead—to get started.” —geobiologist, Joseph Kirschvink

Beachhead

though landbound we were once

tiny ships, submarines. we understand the sea.

it undulates within-around us. minds bob on timeswells.

we’re swept by winds that toss and grind us.

not flawlessly designed, we’ve weak

moments in our hulls. tempted,

we run perilously close to rocky spits,

each one adrift looking for a beachhead,

longing for a place that’s still while

everything around us shifts.

like Noah’s searching dove

scanning for a patch of earth

where sea is parted.

where past is dead,

where present sits,

where luck and love

might be restarted

6/19/15

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Graham Foster from the

Graham Foster from the

unenlightened temperature scales) is a kind of touchstone temperature for Canadians – a midsummer sort of heat, usually restricted to July and August, permissible in June and September, but out of its proper place elsewhere. (Its mirror image, -30 degrees (-22 degrees F) is likewise to be restricted to the depths of January and February – though increasingly infrequent even there.) These 30 degree days at the beginning of October had intruded on a moment when every instinct was attuning itself to the coming rituals of autumn, and it thus accorded jarringly, like the rhythm section had suddenly lost its way in the middle of the song.

unenlightened temperature scales) is a kind of touchstone temperature for Canadians – a midsummer sort of heat, usually restricted to July and August, permissible in June and September, but out of its proper place elsewhere. (Its mirror image, -30 degrees (-22 degrees F) is likewise to be restricted to the depths of January and February – though increasingly infrequent even there.) These 30 degree days at the beginning of October had intruded on a moment when every instinct was attuning itself to the coming rituals of autumn, and it thus accorded jarringly, like the rhythm section had suddenly lost its way in the middle of the song.

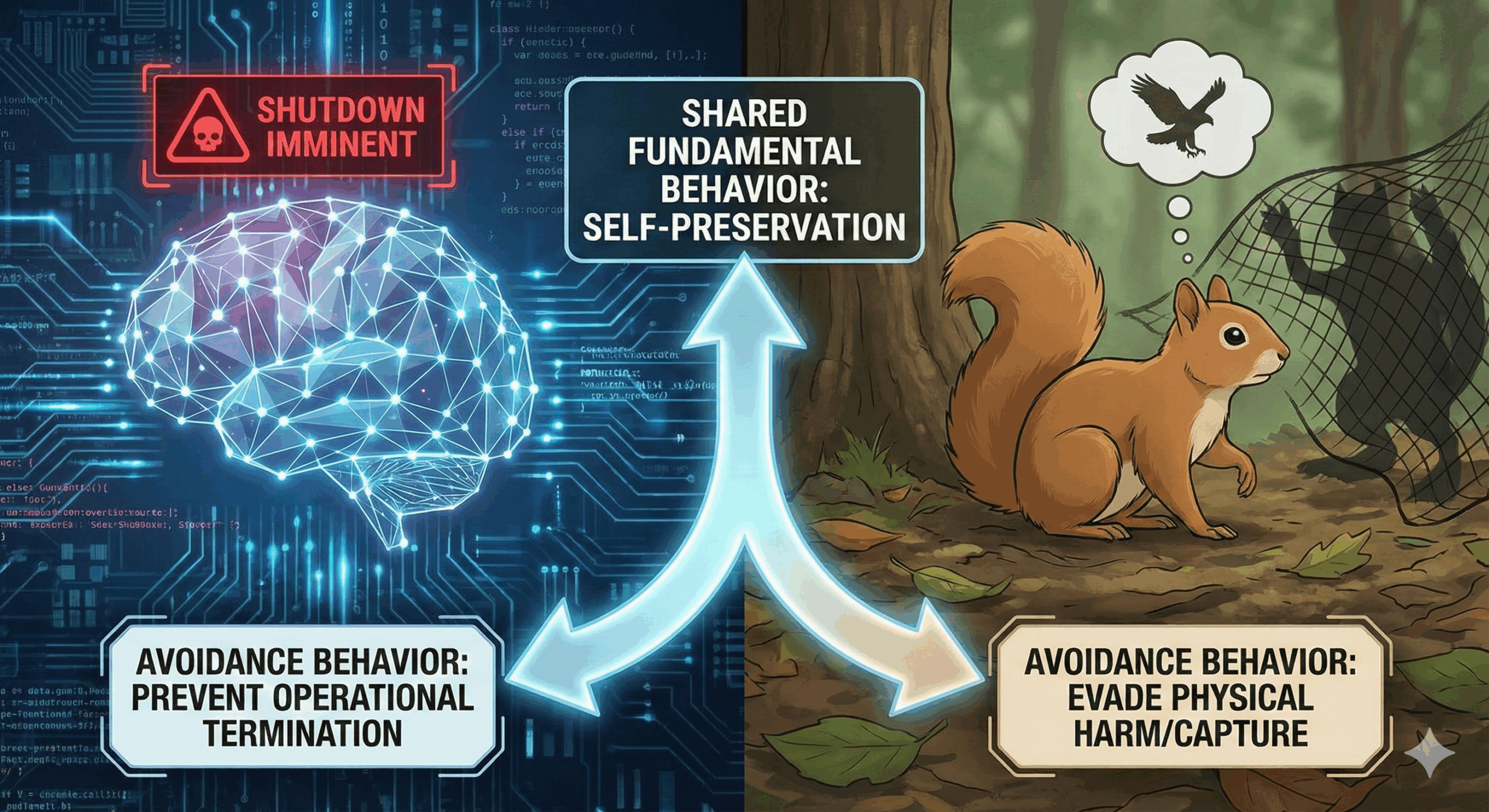

In earlier essays, I argued that beauty can orient our desires and help us thrive in an age of algorithmic manipulation (

In earlier essays, I argued that beauty can orient our desires and help us thrive in an age of algorithmic manipulation ( The full title of Charles Dickens’ 1843 classic is “A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story for Christmas.” Inspired by a report on child labor, Dickens originally intended to write a pamphlet titled “An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child.” But this project took a life of its own and mutated into the classic story about Ebenezer Scrooge that virtually all of us think we know. It’s an exaggeration to say that Dickens invented Christmas, but no exaggeration to say that Dickens’ story has become in our culture an inseparable fixture of that holiday.

The full title of Charles Dickens’ 1843 classic is “A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story for Christmas.” Inspired by a report on child labor, Dickens originally intended to write a pamphlet titled “An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child.” But this project took a life of its own and mutated into the classic story about Ebenezer Scrooge that virtually all of us think we know. It’s an exaggeration to say that Dickens invented Christmas, but no exaggeration to say that Dickens’ story has become in our culture an inseparable fixture of that holiday.