by Malcolm Murray

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“Humans are lucky to have Yudkowsky and Soares in our corner, reminding us not to waste the brief window that we have to make decisions about our future.”— Grimes

Probably the first book with blurbs from both Ben Bernanke and Grimes, a breadth befitting of the book’s topic – existential risk (x-risk) from AI, which is a concern for all of humanity, whether you are an economist or an artist. As is clear from its in-your-face title, with If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies (IABIED), Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares have set out to write the AI x-risk (AIXR) book to end all AIXR books. In that, they have largely succeeded. It is well-structured and legible; concise, yet comprehensive (given Yudkowsky’s typically more scientific writing, his co-author Soares must have done a tremendous job!) It breezily but thoroughly progresses through the why, the how and the what of the AIXR argument. It is the best and most airtight outline of the argument that artificial superintelligence (ASI) could portend the end of humanity.

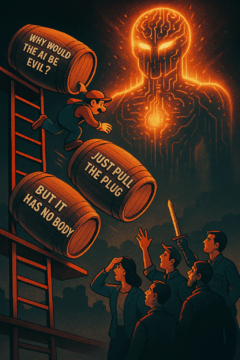

Although its roots can be traced back millennia as a fear of the other, of Homo sapiens being superseded by a superior the way we superseded the Neanderthals, the current form of this argument is younger. I.J. Good posited in 1965 that artificial general intelligence (AGI) would be the last invention we would need to make and in the decades after, thinkers realized that it might in fact also be the last invention we would make in any case, since we would not be around to make any more. Yudkowsky himself has been one of the most prominent and earliest thinkers behind this argument, writing about the dangers of artificial intelligence from the early 2000s. He is therefore perfectly placed to deliver this book. He has heard every question, every counterargument, a thousand times (“Why would the AI be evil?”, “Why don’t we just pull the plug?”, etc.) This book closes all those potential loopholes and delivers the strong version of the argument. If ASI is built, it very plausibly leads to human extinction. End of story. No buts. So far, so good. As a book, it is very strong. Read more »

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

In

In

In a recent essay,

In a recent essay,

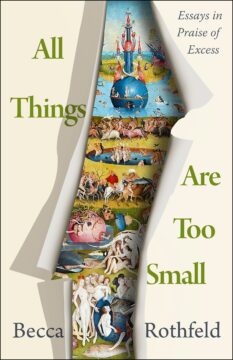

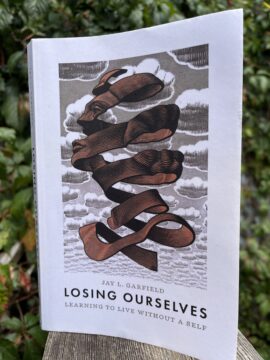

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.