by Christopher Hall

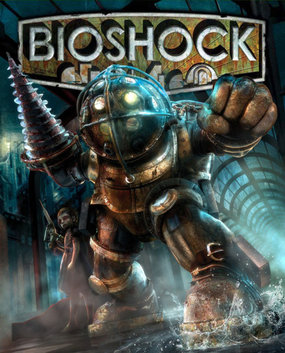

2007’s Bioshock stands as a touchstone for many on the by-now perennial, and admittedly somewhat tiresome, question of whether video games are or could be art. I remember the game for what one remembers most first-person-shooters for – the joy of slaughtering successive waves of digital monsters – but there is one moment in the game that stands out in a different way. (Spoilers ahead.)

As is typical in these sorts of games, you are given tasks, usually by a non-player character (NPC) of some sort, which you must complete in order to progress the game. The NPC – Altas – prefaces all of his requests to the player character (PC) – Jack – with the phrase “Would you kindly.” It turns out that Jack has been conditioned to do whatever he is told when a request is so phrased. In a distinctly postmodern-ish moment, the player is called upon to think of themselves in relation to the PC. They are not compelled in the same way Jack is, but absent quitting the game entirely, they have no other option but to continue. You can either do what you are assigned to do or abandon the system entirely (food for thought there). Add to this the overall setting of Bioshock: a dystopia initially created by an industrialist operating under a libertarian ideology recognisably derived from Ayn Rand. So the ultimate quest for social and economic freedom conceals instead brutal coercion. I am not silly enough to attempt a definition of aesthetic sensation, but the frisson this caused was enough to qualify in my mind.

Is Bioshock art? Could it be art? It is 20 years since Aaron Smuts asked “Are Video Games Art?” in Contemporary Aesthetics (responding to a 2000 article from Jack Kroll who firmly answered “no”), and 16 years since John Lanchester asked roughly a similar question (“Is It Art?”) in the London Review of Books. Smuts noted that there is already a tenuous distinction between art and sports:

Although we may say that a baseball pitcher has a beautiful arm or that a boxer is graceful, when judging sports like baseball, hockey, soccer, football, basketball and boxing, the competitors are not formally evaluated on aesthetic grounds. However, sports such as gymnastics, diving and ice skating are evaluated in large part by aesthetic criteria. One may manage to perform all the moves in a complicated gymnastics routine, but if it is accomplished in a feeble manner one will not get a perfect score….One might argue that such sports are so close to dance that they are plausible candidates to be called art forms.

Even if video games are essentially competitive, Smuts notes, just because that is the case does not render them “inimical” to art. If one enters a poem in a poetry contest and wins, one’s poem does not cease to be art. Read more »

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take

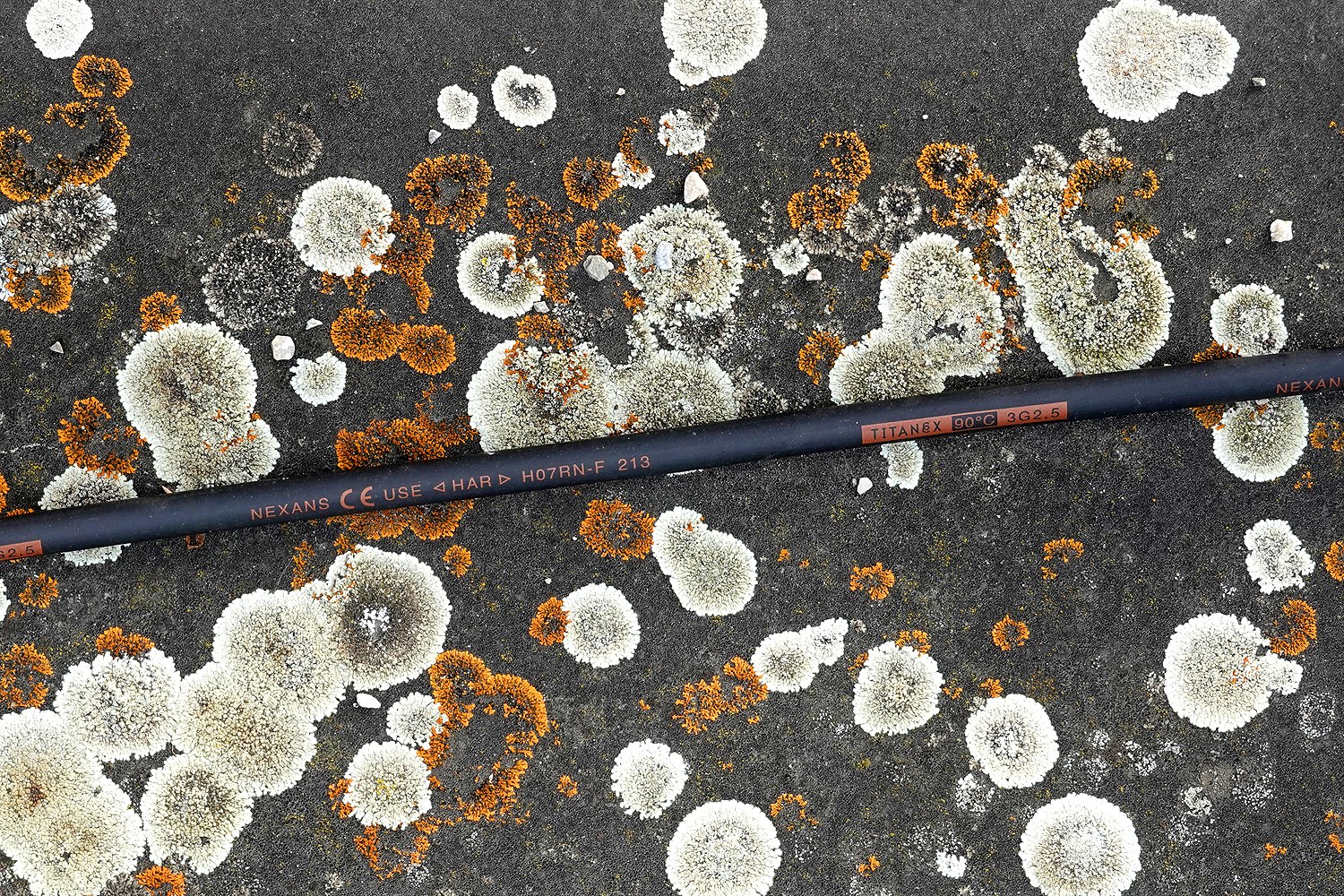

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.