by Akim Reinhardt

There’s a lot going on right now. Lowlights include racism, misogyny, and transphobia; xenophobia amid undulating waves of global migrations; democratic state capture by right wing authoritarians; and secular state capture by fundamentalist Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu nationalists.

There’s a lot going on right now. Lowlights include racism, misogyny, and transphobia; xenophobia amid undulating waves of global migrations; democratic state capture by right wing authoritarians; and secular state capture by fundamentalist Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu nationalists.

Among the many factors causing and influencing these complex phenomena are: the rebound from Covid lockdowns and the years-long economic upheavals they wrought; brutal warfare in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa among other places; and intense weather-related fiascos stemming from the rise in global temperatures. But one I’d like to focus on is a growing sense of male insecurity.

The latest “crisis” in masculinity is not more important than other issues. However, I’m currently attuned to it for several reasons. One is that as I wade through late middle-age, I’m becoming ever more secure in (ie. relaxed about) my own masculinity, which in turn leads me to better notice gender insecurity in other men. Another is that I believe American male insecurity played a vital role in the recent election of Donald Trump and, as such, demands attention. Qualitative and quantitative data about Trump getting more votes than expected from young men with college education, from black men, and from brown men, signal something. And finally, as a historian, shit storms rising up from perceived crises in masculinity are not new to me.

In the United States, a broad crisis of white masculinity first emerged during the early 19th century. Then, as now, it was driven by economic changes and by challenges to established patriarchy, and it found expression in religion and politics.

During the colonial era and the early years of the new nation, patriarchy was deeply entrenched in American culture. Indeed, it did not look entirely different from patriarchies in other parts of the modern world that now horrify many in the West. Most fathers ruled families with an iron fist. Wives were expected to act not as independent partners, but as mere subordinates who took orders from their husbands and passed them onto the children. White husbands and fathers held nearly all of the citizenship rights and the economic powers, which were legally and culturally denied to women. White men voted; women did not. White men served on juries; women did not. White men, if fortunate enough, owned property and/or businesses; single adult women could only inherit property, and it became their husband’s property upon marriage. And in a nation that was widely and deeply religious, men also provided religious guidance for their families. The family patriarch was boss of his family’s religious tutelage. He said grace (or decided who would), he led them in prayer, and he set the religious agenda.

By the opening of the 19th century, this is more or less how it had been in the colonies and the new nation for nearly two centuries. But changes were afoot.

One important source of change was early urbanization. In 1790, the United States was overwhelmingly rural. Only 5% of Americans lived in towns with so much as 2,500 people; most Americans lived in farm families. But important economic changes were brewing in America’s nascent cities. Freed from British mercantile restrictions, the new U.S. economy quickly embraced the first rumblings of early industrialization. And as early capitalism began to take root, the economic tumult of boom/bust cycles and labor degradation soon followed. This, in turn, disrupted established gender relations.

Relative class stability was replaced by the volatility of shifting winners and losers. As new industries absorbed labor and implemented economies of scale, more and more skilled craftsmen saw their trades rendered obsolete. By mid-century, millions of independent tradesmen and farmers would end up in factories and other venues of poorly paid, manual wage labor. What’s more, by the 1820s, women were also working in factories, particularly in the booming textile industry.

As small businesses and independent labor were being degraded, a new class of white man was emerging. Unlike most American men, he was not a farmer. Instead, he lived in a town or a city. What’s more, he did not even work with his hands, as did urban skilled craftsmen. Instead, he was a new style of merchant, a wholesaler or retailer who made profits by the mathematics of bookkeeping instead of hard, “honest” labor. And those profits began to add up.

These new petty capitalists could lose fortunes as easily as they made them. However, many new urban merchants reached economic heights far beyond the average family farmer or skilled tradesman. Most never became full-on wealthy, but the bulk of them did come to form a new urban middle class that enjoyed luxuries beyond the reach of most, such as: matched grain wood floors, covered by expensive carpets; cast iron stoves; fine clothing for everyday of the week; and servants to cook and clean for them. By the 1830s, some urban homes even had the miracle of indoor plumbing.

Meanwhile, white farmers and skilled tradesmen faced ongoing economic pressures. Tradesmen lost out to the factories of the industrial revolution. “Extra” sons from large farm families, who were not in line to inherit the farm, moved to cities in search of work. The ranks of white, low-paid manual laborers grew. As a class, small farmers and skilled tradesmen were no longer the undisputed second-ranked Americans behind only truly wealthy white men.

A common reaction by white men whose economic standing declined, was to fall back on other sources of privilege, including longstanding patriarchal values and a burgeoning sense of whiteness. They re-emphasized their superiority over women, and embraced new frameworks of racial superiority over African Americans, Native Americans, and even other “white” men. In the free states of the North, white men increasingly resented black slaves. They blamed urban slaves for depressing wages. And they developed a political stance called Free Soil, which aimed to keep slave plantations out of the new Western territories and states so they could become a White Man’s Paradise of small family farms. By the 1850s, many white, native-born men were also targeting Irish and German immigrants, whom they accused of driving down wages, speaking the wrong languages, worshiping the wrong religion (Catholicism), and lacking democracy bon fides. And they begrudged the white men of the new urban middle class. They besmirched the merchants as unmanly for not making their way by the sweat of their brows, and resented them for reaping supposedly ill-deserved gains at their expense.

This crisis of white masculinity also found expression in the great religious revival of the early 19th century known as the 2nd Great Awakening (2GA). It succeeded the 1st Great Awakening (1GA) of the mid-18th century. Or perhaps there was just one big Great Awakening, which was interrupted by several decades of war, revolution, and nation building. Historians still debate the extent to which they’re related and distinct. Either way, a defining element of the Great Awakening(s) is that much of the populace was swept up in a renewed religious fervor spread by a new brand of preachers.

During the 1GA, colonists were attracted to charismatic preachers who challenged older Presbyterian, Anglican (later known as Episcopalian), Puritan (later known as Congregationalist), and related theologies. The older doctrines insisted that Christians must commune with God through a trained, learned interlocutor, who was invariably a white man, a Minister or Elder with some elements of elite standing. But new preachers of the 1GA claimed that people could commune with God more effectively on their own, through faith and prayer. This rejection of strict, institutional religious authority proved a timely spur to the upcoming American Revolution. After all, if you don’t need a religious leader to guide you to Heaven, then you certainly don’t need a king to guide you to good governance.

The 2GA sprouted up at the opening of the 19th century. It peaked in the 1830s, and continued in various forms through the Civil War. And its impact is still very much felt in modern America. Indeed, when people talk of Americans’ supposed “Puritanical values,” that is a misnomer. Puritan values of the 1600s have virtually no effect on us today. They faded away centuries ago, and never had much influence outside of New England and parts of the Midwest. Instead, so-called Puritanical values actually refer, in general, to American Victorian (ca. 1830s–1910s) values, which in turn were greatly influenced by the 2GA.

Certain aspects of the 2GA were a clear continuation of the 1GA, including: the rise of itinerant preachers; emotional, evocative, and often extemporaneous preaching instead of sedate, learned sermons read from behind a podium; a renewed devotion to evangelicalism (spreading the Gospel); and a move away from religious interlocutors in favor of a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

However, some 2GA theological innovations went beyond the 1GA. Instead of formally trained theologians, more and more preachers were now autodidacts. And these self-taught preachers rejected predestination, a Calvinist theology that had been a prominent in American Protestantism up to that point. Predestination asserted that God chose who was going to Heaven or Hell before they were even born. But new preachers dispensed with predestination, and directed Christians to forge their Heavenly path by consciously accepting Christ into their life, and expressing their faith through good acts. Failure to do so was a sure fire path to Hell, because people were born sinners. But their afterlife was not predetermined; they could be saved by consciously accepting Jesus into their life and living a Christian life.

More and more American Christians were attracted to emotional, spontaneous sermons about the spiritual choices they must make, and the potential doom they faced. This led to a widespread urgency over the need to be “saved” so as to avoid eternal damnation. Millions sought salvation through a purposeful devotion to Jesus Christ that followed religious epiphany. This was now seen as a conversion experience, even if the person were already a practicing Christian. Christians would publicly profess a renewed commitment to Christ, and be baptized as adults. This would wash away their prior sins, and their soul would be “reborn,” or “born again” so they could commence an earnest path towards Heaven.

If even practicing Christians needed to be saved through an adult conversion experience, then spreading the Good Word (evangelizing), was now seen as the highest Christian duty. Evangelical camp revivals, where preachers warned of eternal damnation and implored sinners to be reborn, became commonplace across the nation. The first large 2GA camp revival took place at Cane Ridge, KY in 1801. Eventually some 20,000 people (about ¼ of Kentucky’s total population) attended.

The 2GA was not uniform across the United states. There were important regional differences. In the rural South, itinerant preachers with no fixed church address were vitally important. During the 1GA, they had done much to convert Africans and African Americans to Christianity. Previously, most slaves had been uninterested in staid Anglican church services, while many slave owners had resisted converting their slaves, fearing Christian teachings might lead them to rebel. But many slaves were drawn to 1GA preachers’ evocative style of sermonizing, while those same preachers warned slave owners that their own souls were in peril if they denied their slaves the teachings of Christ. However, the 2GA was different. A new generation of itinerant preachers still traveled throughout the South, holding camp revivals and preaching the gospel. But now their sermons tended to reinforce racial and patriarchal hierarchies that were central to the Southern social order. Thus, religion continued to function as a cultural institution through which white men could define their patriarchal masculinity.

The North was less homogeneous than the South. While the nation was still overwhelmingly rural, Northern cities were appearing and growing at rates that far exceeded the South. In the North, 2GA religious movements began to fissure along urban/rural lines. Much of that difference revolved around patriarchy.

In the bustling new cities of a young nation, the 2GA challenged unbridled patriarchy. Many of the well-to-do merchant men were open to a new Christian message that, while not advocating true gender equality, was at least willing to raise women up from complete subservience. And in a startling development, many urban 2GA preachers preached directly to women, engaging them in ways that other preachers did not. They offered a new message, talking about women’s vital roles in Christian families. And that new message helped change American gender relations by identifying the home as the realm where wives could make direct contributions and important decisions instead of simply bowing to their husband’s orders. Indeed, many Americans would eventually come to see women as being in charge of the home.

This was, however, not about gender equality. New middle class urban men still saw women as physically and intellectually inferior, and had no intention of letting their wives and daughters exert any authority outside the home. But they came to understand white, Christian women as having natural nurturing talents and skills, which qualified them to run aspects of the family home even without much male guidance. They believed women could: design the home to make it a regenerative, Christian space; make important decisions about child rearing; and even take the lead, or at least be co-equal, on matters of grace and prayer.

Northern 2GA preachers, such as the highly successful Charles Grandison Finney, advanced this new gender-relations model, particularly in cities and among the new middle class. Finney and his kind warned that worldly power corrupts. It needed to be countered with Christian love, which welled up more easily in women. But many rural Northerners rejected this feminized Christianity. They despised the new merchant class, derided white collar men as effeminate, and castigated them for handing over the reins of familial power to their wives.

Some rural 2GA preachers angrily warned that the end times were near. They rang the alarm about all that had supposedly gone wrong with Christianity, including its new effeminacy. One infamous masculine preacher of the 1830s was Robert Matthews. Styling himself the Prophet Matthias, he claimed the End Times were near. All real men would be saved, while the insufficiently manly would be damned; women were an abomination who needed to become obedient at once; it was wicked to teach women or preach to them directly; and women who lectured their husbands were to be cast out. Matthews issued a list of those who would be judged. Among them were “All women who do not keep at home, All who preach to women without their husbands,” merchant tailors who hired women workers, real estate dealers, and men who wore glasses. Matthews was a highly controversial extremist and atypical in many ways. But he was also in line with rural 2GA preachers in the North and South who promoted patriarchy.[1]

Much of this should sound familiar. In more recent decades, American patriarchy has again been challenged by changing gender roles arising from widespread economic tumult. And the defense of patriarchy has again found religious and political expression.

During the early-mid 20th century, blue collar white men, often with the help of labor unions, adapted to the industrial revolution and reordered their masculinity. Particularly after WWII, they cast themselves as hardworking breadwinners whose own wives could stay at home (at least while the children were small and if everything went well), much like the upper middle class wives of the white collar classes. But starting in the 1970s, deindustrialization upended 20th century American patriarchy. As good paying factory jobs requiring little or no formal education began drying up, fewer blue collar men could rise to the status of sole breadwinner. More and more wives entered the workforce. And as good salaries have flowed to white collar work, women’s college attendance rates have steadily increased to where they are now the majority of students. This has enabled them to get white collar jobs that often pay as well or even better than traditional “men’s” work. By the 1980s, the new crisis of American masculinity was upon us.

The loss of middle class factory jobs requiring no formal education; the assumption of many skilled trade jobs by immigrants who are willing to work harder and longer for lower wages; post-1960s feminism’s tremendous strides against American patriarchy (even as it still has a long way to go); and the rise of yet another, white collar middle class, based not on merchant activity as in the 19th century, but on administration, technocracy, and finance, and which demands credentialed education in the form of college degrees, and even graduate degrees, which are increasingly earned less by white men, and more by immigrants and women: all of these factors have challenged American patriarchy and contributed to a crisis in American masculinity.

And once again, amid economic changes that challenge patriarchal gender roles and even white supremacy, we see men scrambling to redefine their masculinity. How else to explain, for example, a social phenomenon so seemingly incongruent and paradoxical as that of the “tech bro?” Pulsing, chest-pounding masculinity among men who spend all day staring at screens and typing. It would be comical if it weren’t toxic.

And of course the patriarchal strains of Christianity that dominated rural, ante-bellum America have evolved in many ways, but never really went away. As the nation steadily urbanized during the 19th century, and then suburbanized after WWII, rural Americans became a small minority of the population. By the mid-20th century, evangelical Christianity seemed like a provincial vestige of an earlier age. But conservative Christianity was publicly reactivated with the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s. No longer willing to leave participatory politics to the mainline Protestant denominations descended from the Finneyites and other liberalizing, urban 2GA Christianities, conservative evangelical Christians began asserting their cultural and social agendas. They’re now louder and stronger than they’ve been since the 19th century. Evangelical Christian churches across rural and exurban America idealize patriarchal family models. Whether it is championing patriarchal family arrangements, establishing male control over women’s bodies (particularly vis a vis sexuality and reproduction), or rabid homophobia and now transphobia, the conservative Christian right’s stance on gender issues is decidedly 19th century, and has found renewed vigor amid economic changes that challenge the preeminence of white men.

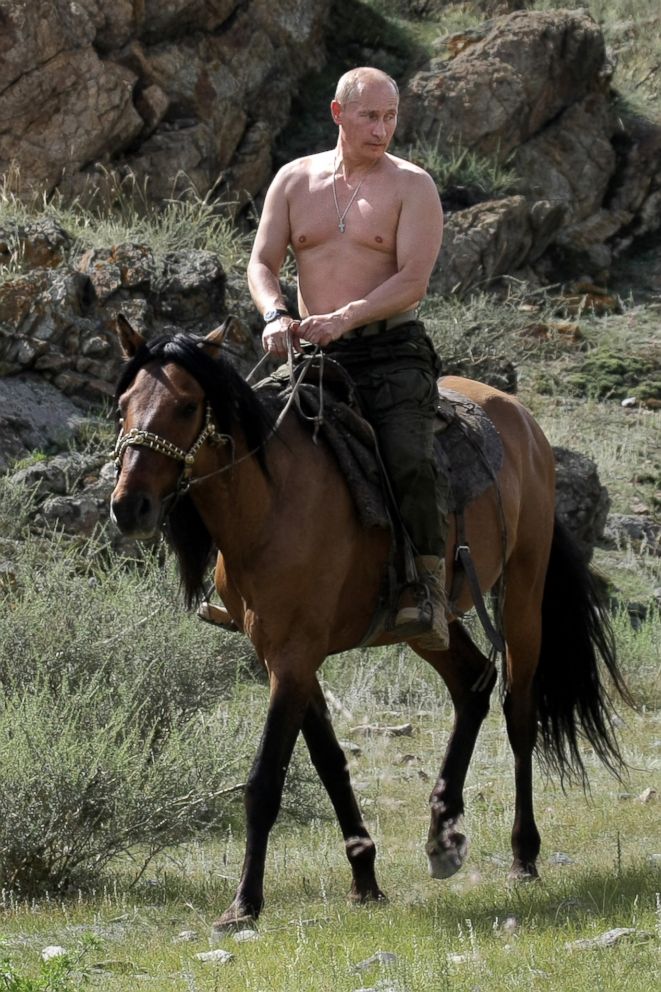

Perceived crises in white masculinity have always found political expression. Today it’s Trump. Two-hundred years ago it was macho politicians such as Andrew Jackson. No wonder Trump kept Jackson’s portrait in the Oval Office. And no wonder the world’s other current and former right wing authoritarians of the last decade have likewise cultivated hyper-masculine personas. Whether its Vladimir Putin’s bare-chested horseback riding, or the rhetoric and/or antics of Rodrigo Duterte (Philippines), Shri Narendra Modi (India), Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (Turkey), Viktor Orban (Hungary), Jair Messias Bolsonaro (Brazil), and others, current and recent former strongman dictators and would-be dictators appeal to economically displaced men who long to assert their dominance. We may debate whether or not they are actually fascists. But either way, they are modern day saviors, offering salvation not in the next life, but in this one. They preach to citizens who fear the feminization of the economy, the rise of LGBT equality, the blurring of racial boundaries, and the reorganizing of “traditional” family structures.

Perceived crises in white masculinity have always found political expression. Today it’s Trump. Two-hundred years ago it was macho politicians such as Andrew Jackson. No wonder Trump kept Jackson’s portrait in the Oval Office. And no wonder the world’s other current and former right wing authoritarians of the last decade have likewise cultivated hyper-masculine personas. Whether its Vladimir Putin’s bare-chested horseback riding, or the rhetoric and/or antics of Rodrigo Duterte (Philippines), Shri Narendra Modi (India), Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (Turkey), Viktor Orban (Hungary), Jair Messias Bolsonaro (Brazil), and others, current and recent former strongman dictators and would-be dictators appeal to economically displaced men who long to assert their dominance. We may debate whether or not they are actually fascists. But either way, they are modern day saviors, offering salvation not in the next life, but in this one. They preach to citizens who fear the feminization of the economy, the rise of LGBT equality, the blurring of racial boundaries, and the reorganizing of “traditional” family structures.

Have faith that we will overcome.

***

[1] See: Paul E. Johnson and Sean Wilentz, The Kingdom of Matthias (Oxford University Press, 2012. 1994)

Akim Reinhardt’s wesbite (currently under reconstruction) is ThePublicProfessor.com

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.