by David Greer

The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random.

The smallest spider I’ve ever seen is slowly descending from the little metal lampshade above my computer. She’s so tiny, a millimeter wide at most, I have to look twice to make sure she isn’t just a speck of dust. The only reason I can be certain that she’s not is that she’s dropping straight down instead of floating at random.

It’s become almost automatic to reach for the iPhone to obtain a visual record of a wildlife encounter out of the ordinary, and so I do. However, the spider’s size and the fact that she’s now spinning like a miniature dervish presents a challenge beyond my iPhone’s capabilities. You’ll just have to take my word for it that that’s her in the image to the right, the tiny golden blob to the left of the lamp stem.

Perhaps I shouldn’t make assumptions about the spider’s gender, but her size makes verification problematical. Ever since I fell in love with Charlotte’s Web I’ve been inclined to think of spiders as feminine in the absence of evidence to the contrary. I would no more call her an “it” than I would a human, and she doesn’t strike me as a probable “they.” So “she” it will have to be.

Having observed many swarms of aimlessly scrambling baby spiders fresh out of their communal egg sacs, I know that in the not distant future she’ll be many times her current size. And however small she may be today, a few clicks worth of research confirms that she’s a giant compared to some of her cousins. A full-grown Patu digua, quite possibly the smallest spider species on the planet, maxes out at around 0.37 millimeters, about four times the width of an average human hair (75 micrometers).

Accurately determining the size of the tiniest creatures on the planet can be a challenge using standard units of measurement. Read more »

Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024.

Naotaka Hiro. Untitled (Tide), 2024. In a previous essay,

In a previous essay,

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

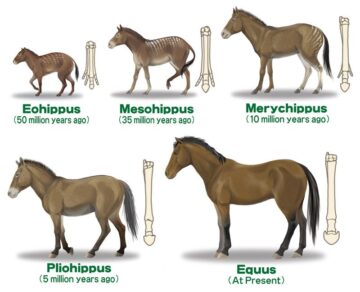

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

We humans think we’re so smart. But a

We humans think we’re so smart. But a Giant Tarantulas

Giant Tarantulas

by Steve Szilagyi

by Steve Szilagyi Jaffer Kolb. Lake Mývatn, October 13th, 12:08 am.

Jaffer Kolb. Lake Mývatn, October 13th, 12:08 am.