by Thomas Fernandes

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

On the savanna after rain, the sequence of consumption illustrates this principle. Zebras arrive first, grazing vast quantities of coarse grass. Their hindgut fermentation extracts energy efficiently but incompletely, favoring volume over quality. Sixteen hours of grazing may be required to meet their energy needs. Gazelles arrive afterward, targeting smaller, more nutrient-rich shoots. Their rumen, a multi-chambered stomach, allows for regurgitation and thorough microbial digestion. The slower, more meticulous process extracts more energy per bite. Reproduction and survival hinge on the energy accumulated this way. Gestation and nursing occur only during seasons of peak grass growth and only when the gazelle has the metabolic green light of sufficient energy.

This extracted energy inevitably attracts predators. Predator-prey interactions extend far beyond the immediate chase. While roaming for prey, predators exhibit preferential roaming, patrolling region most likely to contain their favored prey and encountering them far above chance level. Even when encountering prey, predators decide to initiate the hunt with calculated strategies. Lions exploit cover, coordinating in groups to ambush large prey like buffalo. Cheetahs, mostly solitary, approach carefully to close the distance before committing to a sprint. Predators weigh energy costs, prey size, terrain, and detection before deciding to pursue. Selecting targets with high probabilities of success is critical.

Prey respond with equally finely tuned adaptations. Gazelles detect predators early through lateral eyes, motion-sensitive retinas, and vigilance. Zebras would stand their ground against a solitary, small cheetah but have evolved rotating ears to detect the more threatening, camouflaged lions’ ambush. Early detection and avoidance are ideal, but when impossible, prey rely on alternative strategies.

When Thomson’s gazelles spot a hunter, they often spring into stiff-legged leaps, rump pointed toward the predator, rather than immediately fleeing. This is called stotting and at first, seems reckless. Yet the leaps are a signal, a declaration of fitness. To the stalking predators, looking to maximize their odds, this is the prospect of hard and exhausting chase. It is a strange sight: prey speaking to predator. Wild dogs, built for endurance, often read the display and abandon the hunt or shift attention to a weaker gazelle in the herd. Cheetahs, sprinters, are harder to dissuade. Once close enough, no display matters: the hunt will not be decided on endurance. In these exchanges, pursuit and escape are not only physical contests but conversations, each side probing the other before the chase even begins.

When the hunt begins, physiology takes over. Prey are not perfect evaders; their musculoskeletal and metabolic systems must also support feeding, roaming, and reproduction. Hunting encounters are infrequent, a few times a year. Predators, in contrast, must achieve a minimal success rate to survive. Any energy-intensive strategy that increases capture probability is favored. Over evolutionary time, predator and prey converge toward similar limits of speed, acceleration, and maneuverability, with a slight skew favoring the predator. As highlighted by Wilson et al., “We show that although cheetahs and impalas were universally more athletic than lions and zebras in terms of speed, acceleration, and turning, within each predator–prey pair, the predators had 20% higher muscle fibre power than prey, 37% greater acceleration, and 72% greater deceleration capacity than their prey.” This similarity hints at a deeper logic governing how the chase unfolds between predator and prey.

Predators often begin hunts close to their prey. Being slightly faster allows them to close the gap efficiently, reducing evolutionary pressure to evolve even higher maximum speed. In response, prey rarely sprint at full power; doing so would make their movements predictable and easier to intercept. Maintaining a moderate pace preserves directional flexibility across successive strides, keeping evasive options open throughout the unfolding chase.

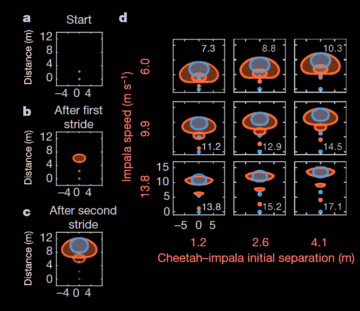

The two-stride model by Wilson et al. formalizes this interaction (Figure 1). Each stride defines an approximately elliptical area of reachable positions for predator and prey, constrained by physiological acceleration limits. The predator reacts with a one-stride delay to the prey’s positioning. Capture probability depends on the overlap of these areas.

Turning, rather than running straight, emerges as the optimal tactic once the faster predator is nearby. By executing lateral accelerations within their stride-limited envelope, prey maximize the number of future positions they can reach while avoiding predictable forward paths. High forward speeds reduce turning angle, while too slow movement allows predators to close the distance over repeated strides. For impala, speeds above roughly 12 m/s exceed the limit at which sharp turns remain feasible. Submaximal speed is therefore crucial for effective evasion.

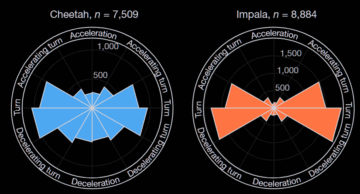

Moderate speed combined with strategic turning creates the “sweet spot” where capture probability is minimized. Figure 2 shows that herbivores often execute near constant-speed lateral turns, as predicted by the model, rarely accelerating or decelerating. Predators often decelerate, either alone or combined with a turn. Predator deceleration compensates for their slightly higher approach speed, allowing them to intercept prey attempting sharp turns.

Real hunts typically involve successive two-stride interactions. Predators’ superior ability to accelerate and decelerate effectively makes continued pursuit possible even after initial evasion. This explains why, despite model predictions suggesting lower speeds might be safer, impala typically escape at high speed. The goal is to end the chase by creating sufficient distance between predator and prey.

In short, survival depends not only on raw velocity but on strategic evasion, playing each part as skillfully as possible. Any reduction in speed or agility, by injury or old age, quickly shifts the odds against the less athletic. In the high-stakes game of the hunt, bluffing alone does not win. Cheetahs’ superior athleticism corresponds to a 40% success rate in observed hunts against impala.

In this short video, two successive cheetah hunts are shown. In the first, the impala avoids entering the two-stride zone, escaping thanks to early detection and sufficient speed. In the second, the predator closes in, and the impala executes a textbook constant-speed turn.

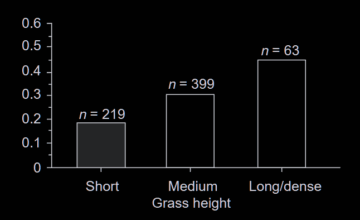

The chase itself reflects a series of finely tuned strategies. Beyond these mechanics, the terrain and ecological context shapes which strategies are possible. Open grasslands favor cheetah sprints; weighing around 40 kg, they can exploit their top speed over distances of 300 meters and more. Lions, three times as heavy, rely on cover to ambush larger prey such as zebras. They begin their hunt within 50 meters and rarely pursuing beyond 100 meters. Figure 3 highlights how critical vegetation cover is for the success of ambush strategies. These constraints feed back into prey adaptations discussed above: stotting to avoid a long chase, rotating ears for detecting ambush.

Prey size further constrains the dynamics. Small animals provide insufficient energy payoff. Larger ones introduce risk: their hooves or horns can injure predators, and group defense can overwhelm a lone hunter. A theoretical hunting match between a cheetah and a zebra might suggest near 100 percent capture probability. Yet in practice, cheetahs rarely attempt to hunt zebras. The risks of injury make such pursuits impractical. Similarly, a lone lioness cannot take down adult buffalo. But lions can hunt in groups. Coordinated groups targeting isolated or distracted individuals can succeed. Predator decisions are therefore finely tuned not just to abundance but also to relative athleticism, group defense, and energetic feasibility.

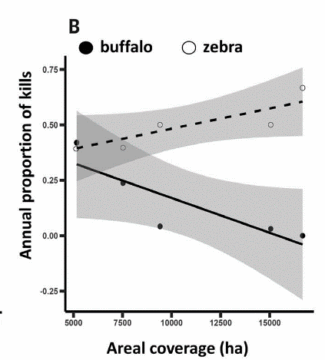

Indirect environmental effects further shape these interactions. About 25 years ago, big-headed ants were introduced in Kenya. Whistling-thorn trees, introduced earlier, constitute between 70% and 99% of woody stems in some regions and rely on symbiotic acacia ants to aggressively deter herbivores. The introduced big-headed ants displaced these defenders while providing none of the protection. The resulting loss of vegetative cover significantly altered hunting grounds: lions faced reduced ambush opportunities, making zebra hunts more challenging, whereas buffalo, which often stand their ground, remained comparably exposed despite the open terrain. Over the year, a change in predation was observed in infested regions and was directly correlated with the amount of available cover (Figure 4). Even the loss of one species can ripple across the ecosystem, subtly altering the balance of populations and interactions.

In the next essay, we will examine how other species have been affected by the necessity to find and preserve energy, developing unique strategies with rippling effects.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.